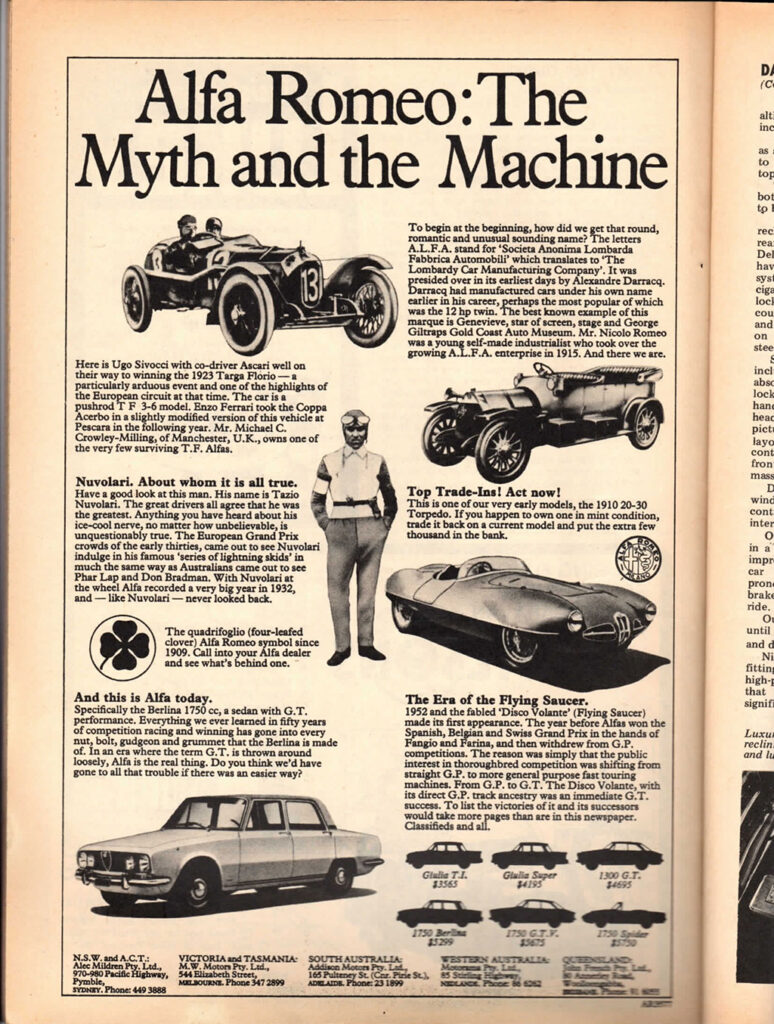

Good evening and thank you for inviting me to this Alfa Romeo Club gathering.

Perhaps now is the moment when I should confess that I’ve never owned an Alfa Romeo….

Despite this obvious failing, I still consider myself an authentic Alfisti. Let me explain: I’m still not sure which comes first: do great drives make great cars, or do great cars make great drives? Either way, these are drives that transcend objectivity and frequently become fountains of motoring inspiration. A talent that seems a natural extension of time spent at the wheel of so many Alfas.

When planning this talk, it naturally followed that I began a list of memorable Alfa drives. Except, a few moments thought, produced a too long list of unforgettable highlights.

In no particular order, they include taking the longcut route for an overnight drive from Melbourne to Sydney in a 2000 GTV.

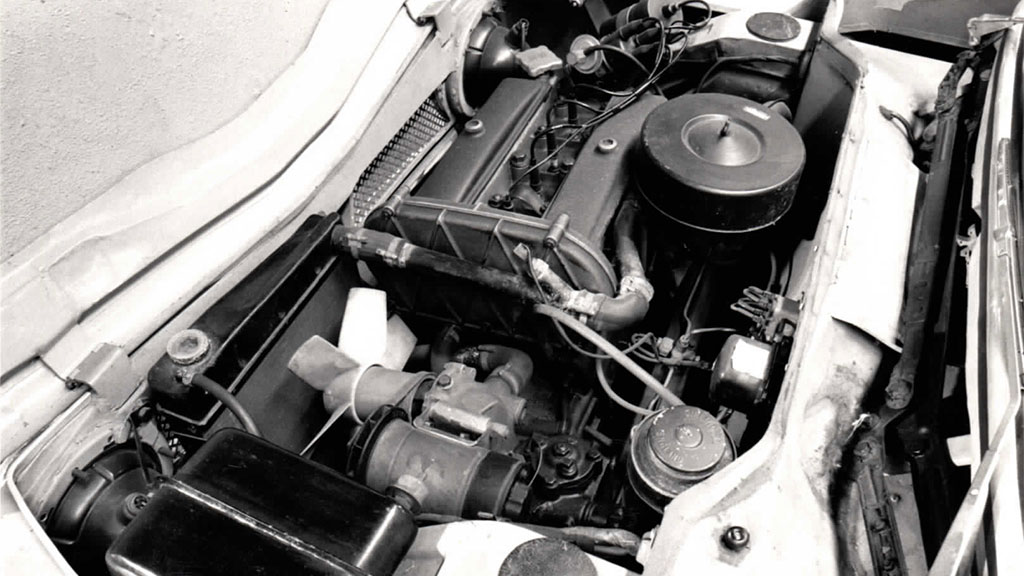

The Bell’s Line of Road proved that by 1974 the 105’s technology was already old. Yet nothing could detract from the Alfa’s spirit, its class or the flexibility and enthusiasm of the twin-cam four, the gear lever an extension of my arm, the steering taut, the rear end jiggling over the road’s uneven surface, all communicating the car’s character and engineering so that we were together, partners in the adventure.

A year later I took an original Alfetta GT from Rome to Barcelona and return for my first World Championship Grand Prix. Left hand drive, so the tacho, rightly, took pride of place as the only instrument in front of the driver, something not repeated on the cars for Australia. The 705km run back from Monaco to Rome was covered in 4 hours and 40 minutes for an average of 151 km/h. It was, I wrote, “the right way to drive, and the safe way.”

The GT also spent time at Balocco, Alfa’s famous test track in the rice fields of northern Italy where, appropriately, corners duplicate those from famous Grand Prix circuits: Curva Grande and Lesmo from Monza, Tarzan from the old Zandvoort circuit in The Netherlands. It was here I learned that cornering hard in the Alfetta required early steering lock to combat the inherent understeer that was apparently a function of the De Dion rear suspension. Once understood, I quickly came to appreciate the GT’s driver appeal and swiftly learned not to hurry gear changes, especially into second.

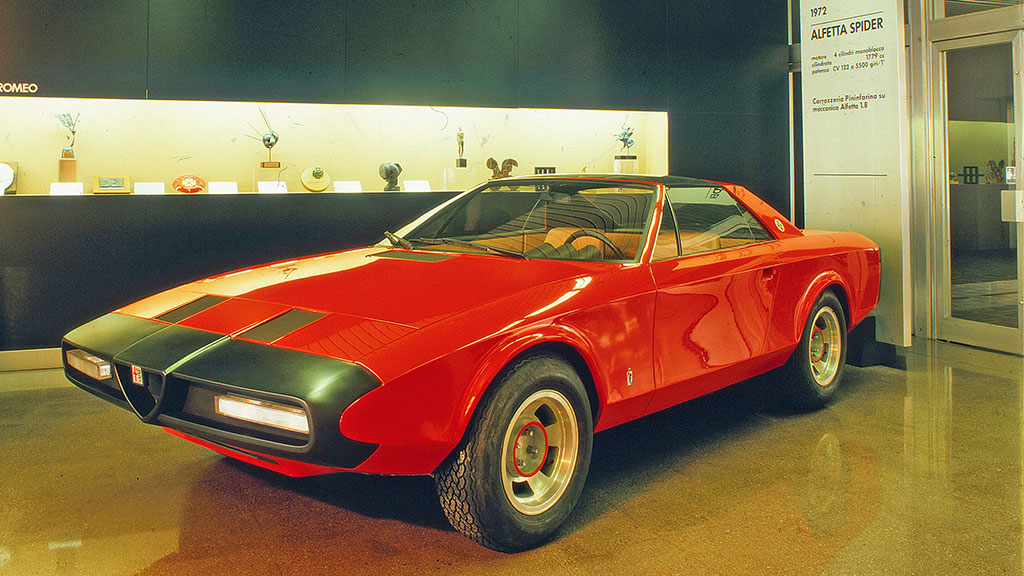

We spent a morning in the Alfa Museum close to the company HQ in in Arese, soaking in the wonderful cars and admiring the many beautiful racing and sports cars. I also came across what I thought was a Renault R8. I remembered Alfa assembled the Renault Dauphine in the old Portello plant, so wasn’t too surprised. Except, a closer look revealed that this was a 1954 protype of an Alfa small car, the Tipo 103, that never went into production.

Alongside the car was a lovely little twin overhead camshaft 896cc engine, obviously designed to be mounted transversely to drive the front wheels. This, years before the Mini.

In the early 1950s, Alfa realised it needed a high-volume car in order to be viable. That meant going smaller and, inevitably, confronting Fiat. Once Fiat became aware of the project it began lobbying the Italian Government – remember, Alfa was state owned – at every level – including the Pope – to abandon the project. So effective was the push that Alfa was forced to cancel the program. Later, Fiat tried the same tactic to stop the Sud. This time the government resisted the pressure because the Sud was to be built in the depressed south.

Before it was abandoned, the Tipo 103 project got to the stage of having laid down a new assembly line. This sat idle until in 1958, Alfa signed an agreement with Renault to build the Dauphine and sell it through Alfa dealers.

The deal included clauses for future technical cooperation between the two companies. Which leads me to the thought: did the 103 influence the R8? Yes, the Renault is rear engined, but the styling is surely too similar to be coincidence…If only applies to so many prototypes that never went into production, but what a jewel the 103 would have made if it had hit the market in the mid-1950s.

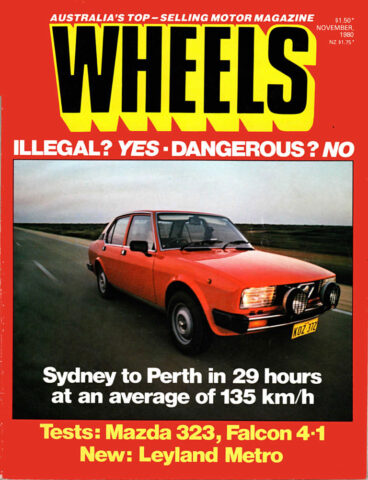

In 1980 my colleague and friend Steve Cropley and I drove an Alfetta sedan from Sydney to Perth, stopping only for fuel and to debug the windscreen. We first drove from the Pacific to the Indian Ocean in 1977, only months after the final section of the Nullarbor Plains Road was sealed, for a Wheels magazine story. I’ll admit we did it for no-other reason than because we wanted to. It was a giant self-indulgence of the very best kind. Our wheels: a specifically built Falcon XC 4.9-litre V8 with the long range 125-litre fuel tank and tall gearing. On that occasion, we took 32 hours 58 minutes, averaged 123.9km/h, the Falcon returning a hideous 23.5l/100km.

Three years later, I learned that Alfa dealer and former racer Brian Foley wanted to prove you could comfortably drive an Alfa from Sydney to Perth in 40 hours over a weekend. After much discussion with Brian and much support from Alfa Australia, an Alfetta 2-litre sedan was prepared for our record attempt. To the totally inadequate 49-litre fuel tank they added a 70-litre auxiliary tank, driving lights and Koni dampers. Cropley, flew out from the land of the Pom where he worked on Car magazine, to reunite the team. Alfa insisted mechanics meet us at two key points along the route – Broken Hill and Port Augusta – just in case there was a problem. This was nothing less than a full works drive. No pressure then.

Worked, too, with Cropley playing hero driver, we successfully reduced the time to 29 hours 14 minutes and five seconds, to establish what I still believe is a record for the cross continent journey. The Alfetta averaged 137.5km/h and 16.6l/100km…and caught just seven red lights along the 4020km route.

In 1978, I’d hoped to spend three weeks in Europe with the new Alfasud Coupe, instead I wound up with a 1.3-litre 5-speed Sud Super sedan. Far more than just an adequate substitute. I experienced again the steering, brakes, agility, space and, above all, the brilliant handling and roadholding that placed the Sud in the very highest bracket of small cars.

But the Alfasud’s intrinsic qualities never had a chance.

Years later, in 1990 when living in Italy, I interviewed Rudi Hruska, the father of the Sud.

By the mid-1970s, Hruska was managing director of the Pomigliano d’Arco plant, near Naples, where the Sud was built, and preoccupied with union problems, absenteeism that sometimes-reached 100 percent a week, and clashes with management in both Rome and Milan. But his biggest problem, the one that led to the Sud’s reputation, was poor paintwork and lousy resistance to corrosion, created by the use of cheap Russian-sourced steel. A production rate that existed on paper could never be reached in reality. The Naples plant stopped and started chaotically and mostly ran at about half its theoretical daily rate.

Although the car’s mechanicals achieved a fine reputation – the engine was later fitted to the 33 and 145/146 and survived until January 1997 – while the handling remained peerless throughout its 12-year life span, Alfa built only 900,000 Suds before it was replaced by the 33. Attempting to run Pomigliano was a “terrible” time in Hruska’s life, but he created a flawed masterpiece.

The most memorable drive involved the Alfa SZ…‘Il Mostro’, a couple of which have made it to Australia.

Thirty years ago, I drove the SZ (the so ugly it’s fabulous, Zagato-built, coupe based on the rear drive V6 75’s platform) from Italy’s north to Palermo. A day later, I set off in the Alfa with Nino Vaccarella to do a lap of the Sicily’s Piccolo Madonie Targa Florio circuit and bathe in the mystique of a unique and wonderful motor race. If there has been a better day as a motoring journalist, I don’t remember one.

“I have driven the course a thousand times,” Nino told me. “I know every corner. Every tree, every stone tells me whether a corner is narrow or wide, if it goes up or goes down. Every centimetre I know. “How many corners? Five, six hundred…the Targa Florio is all corners,” he laughed, the Busso V6 singing soaring, romantic Italian arias as if Verdi composed the engine note.

Fifteen years after Nino Vaccarella last raced around the 72km circuit of public roads, where he won three times, he still had total recall. Back then the flying headmaster from Palermo took on the world’s best drivers and beat them in his own backyard, using his knowledge and not a little driving skill so well that his name became synonymous with Sicily’s great race. You heard about the Targa Florio and you thought of Nino Vaccarella.

Ignoring unobtainable greats like the 1750 Zagato and 8C 2300 Monza, if I could have one Alfa, I suspect the SZ would be close to topping the list.

What made Alfa special was not just the cars, but the people.

Alfas first arrived in Australia in the 1920s and a small number continued to be imported after the first distributor went broke, including a 6C 1500 chassis raced by Lex Davison’s father.

For a brief period from 1963 the local agent was Harold Lightburn, manufacturer of washing machines and the fibreglass Zeta. Shortly thereafter Mildrens in Sydney and MW Motors in Melbourne became the main distributors.

With sales expanding, the factory took over in 1971 and operated out of a small facility in Artarmon under Doctor Messi. A few years later the urbane Doctor Silvano Tagini took over. Tagini quickly understood how the motoring press worked and took advantage of its enthusiasm for Alfas. Road test cars were now always available and Tagini liked talking to the motoring press.

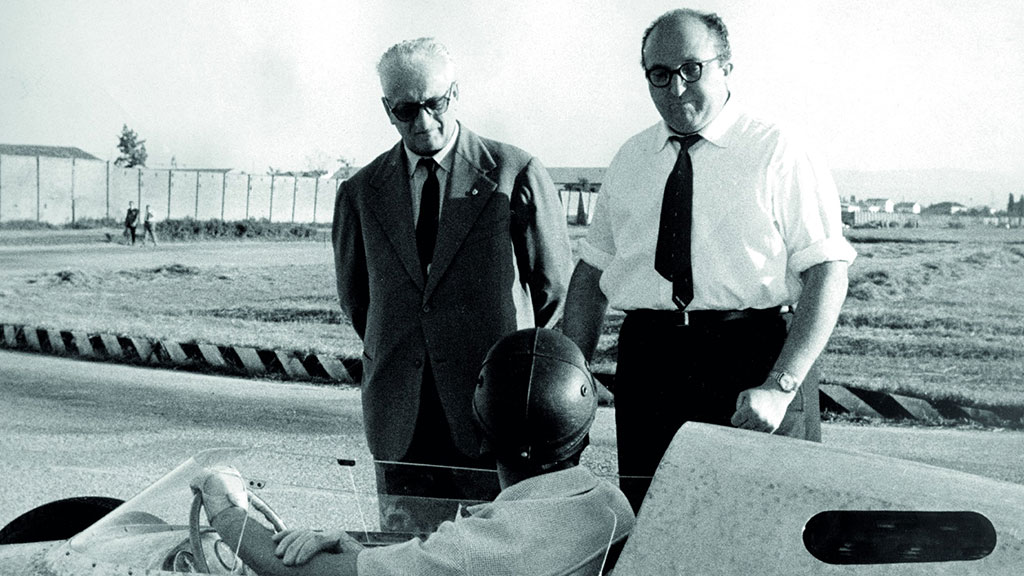

In 1975 he hosted Carlo Chiti and son Arturo, on an “almost holiday” in Sydney. Chiti, the legendary ex-Ferrari engineer – the twin nostril 1961 championship car the Type 33 Alfa sports racing car – where created under his leadership. In 1975 he was head of Alfa’s Autodelta racing team.

Tagini and Chiti braved snowstorms to fly to Bathurst to see the Mount Panorama circuit. “It’s okay for touring cars, but the Grand Prix drivers would never race on its. Some of the corners are too dangerous,” Chiti told me the following day as we cruised the Sydney Harbour. After his acrimonious departure from Ferrari in late 1961, I asked about his current relationship with Enzo Ferrari.

“We are friends, but not very good friends: we respect each other”.

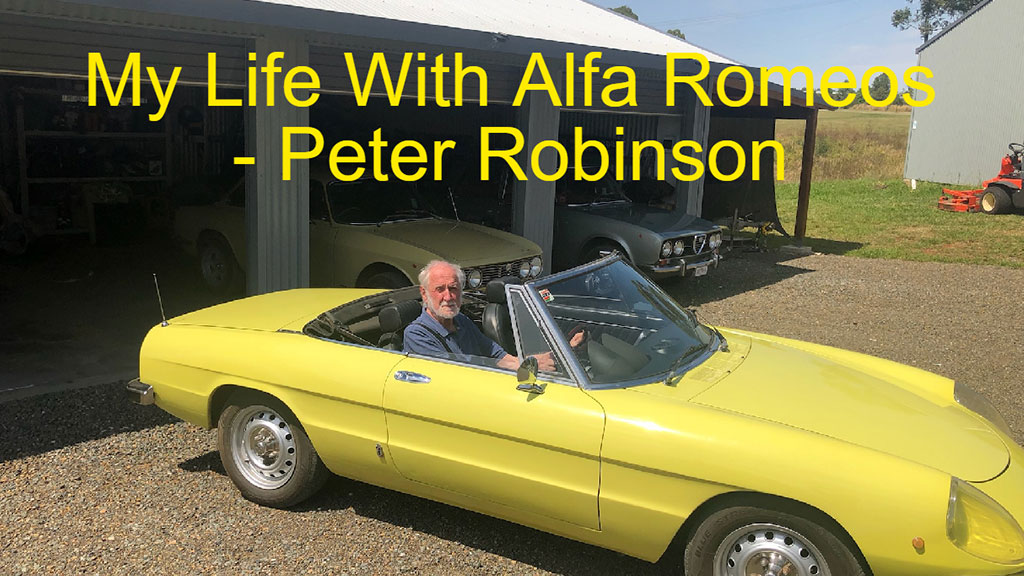

Also in 1975, Tagini arranged for Steve Cropley to borrow a 2000 GTV as his holiday wheels. For this farewell 105 test Steve drove to Cairns, his old stamping ground. The odo read 51 miles when he set off (yes, it still read in miles and not kilometres, years after Australia went metric) and 7000 kms later a broken-hearted Steve returned the car. We now believe that Giallo Piper car belongs to your own Bill McGoffin.

That Alfa was so tiny, the Giugiaro proportions perfect, the pillars delicate, the lines smooth and flowing, even if, perhaps, the final facelift lacked the purity of the original, I was not surprised Cropley returned from holidays besotted.

Nor was I surprised that tiny Alfa Romeo, with quota restricted sales of just 1184 cars in 1975, frequently occupied a disproportionate share of the motoring pages. The Italians realised there was potential for growth.

Tagini open Alfa’s impressive new Matraville HQ in 1976, complete with a professionally run cafeteria for the staff. And it was Tagini who persuade engineer Ruggero Rotondo to come to Australia as Alfa’s chief technical officer. When Tagini departed in 1981, Rotondo took over as MD.

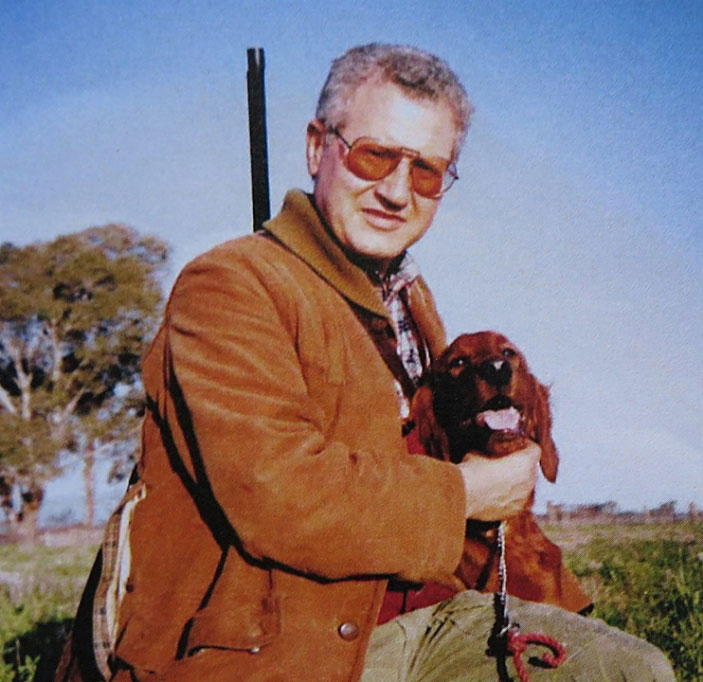

Enthusiastic, charming, jovial and certainly the most loved MD in the Australian motor industry, Ruggero Rotondo always ran Alfa Romeo professionally.

Yet it seemed to us motoring writers that it was also an unofficial branch of Italy’s tourist office.

We called him Roger Round. A term of endearment, though I’m not sure Ruggero ever heard the phrase.

Alfa’s new model launches were always spectacular affairs. Only Alfa Romeo would launch a new car – the 33 – in Venice….and include partners in the invitation.

Alfa trips to Italy, always as much a cultural event as an opportunity to drive the latest models, achieved legendary status in the 1970s.

The 1976 Ciao Tour, seven days in duration, included a “typical” Italian 12-course lunch with wine in a celebrated restaurant in Orvieto. Famously, at around 4.00pm, the happy journalists were advised by their Italian PR-host, “Hurry, hurry, get on the bus or we’ll be late for dinner.”

Any invitation to lunch at Alfa’s Matraville headquarters was accepted with pleasure. If you ate with Enrico Zanarini, Alfa’s super smooth, Armani-clothed, PR and marketing boss, the staff canteen was the location. This was no ordinary canteen – under Ruggero it became a proper Italian restaurant down to the chequered red tablecloths, al dente pasta and balsamic vinegar. We journalists believed this was Sydney’s best Italian restaurant.

You knew you’d moved up the pecking order when you dined alone with Ruggero in the board room: pasta, of course, salad, a choice of fish or meat for the main course – accompanied by wine, Italian of course – followed by an espresso. Then came the famous pressie cupboard from which Ruggero would select one from a collection of Alfa jackets, Alfa briefcases, Alfa model cars, Alfa novelty tool kits and books about Alfa Romeo. Ruggero was the embodiment of the Italian cultural tradition of gifts. They served as something else to connect us to Alfa, Italy and his infectious spirit.

His agile mind worked at a hundred miles an hour, darting from one subject to another…..“By the way…” Ruggero would start, before launching into an unrelated subject. And he drove as fast as his mind worked, as a suspended licence confirmed.

He took the CEO job seriously, buying quota from other importers to get around the import restrictions. He lifted Alfa sales to a peak of 2400 in 1985.

Last year Alfa sold 618 cars in a market almost twice the size.

Ruggero also took Alfa racing with the Australian Alfasud Trophy and persuaded world champ Alan Jones to drive a GTV in Group A, tripling the model’s sales. He went racing and rallying himself, often with Enrico.

It was engineer Rotondo who outfitted the Alfetta sedan that Steve Cropley and I drove from Sydney to Perth.

It was Ruggero who decided the Australian motoring press corps should discover Opera. Mozart’s Cosi Fan Tutti was my, and most of my colleagues’, first opera. A new pleasure for me and a lasting one.

To Ruggero, the saddest thing that could happen was for a journalist to write a critical story of a new model Alfa. When my Wheels road test complained about the driving position of the 33, Ruggero, taking it personally, thumped his chest, “You stab me in the heart.

“I thought you were a friend of Alfa Romeo.”

He once complained to Will Hagon about a fellow motoring journalist.

“This Phil Scott, he says the gearbox is notchy and awful. I think maybe he does not drive like an Italian. How often you n-e-e-d first gear?”

Five minutes later, as Will was leaving, Ruggero invited him to return, “I want you to come back on Tuesday to tell you about the modifications to the gearbox.” He pretended not to see the irony.

It was only when I lived in Italy that I came to realise that being a “friend” to Italian car makers and most Italian journalists, meant never being critical. Few understood the concept of objective assessment from a ‘friend’. Without exception the Italian manufacturers took critical assessment personally, even if it was factual, and immediately you were perceived as the enemy.

Slowly, in the 2000s a more professional – read Anglo-Saxon – relationship developed and they accepted that my love for Alfas – and Ferraris – didn’t prevent criticism.

In 1988, 18-months after Fiat took over Alfa, and aware of the inevitable cultural change, and that sports cars and coupes didn’t figure in Alfa’s mid-term future, Ruggero resigned and moved out of the motor industry.

After he retired, each year Ruggero would spend six months in Naples and six months in Sydney. He loved the outdoors. Sadly his love of hunting led to his death in a road accident on a hunting trip in Estonia in 2016.

I now need to return to cars and the 1990s. In 1992 Alfa sold just 254 cars in Australia. The inevitable followed. In 1993, Alfa pulled out, knowing that it needed to sell 1200 cars a year to break even…

With the 33 now 10 years old, the 75 dead and the 164 still a secret, Turin decided the millions necessary to re-engineer the Fiat-based 155 for the Australian Design Rules was a step too far. Alfas shouldn’t look the way the 155 looked, so part of me was pleased it didn’t come to Australia. Yet I loved the way it felt and drove.

We should go back almost a decade to 1986, when Fiat stole Alfa from a keen Ford, who understood the potential of the near penniless firm. Inexorably, control of Alfa shifting from Milan to Turin with senior Fiat management making the key decisions, including the controversial move to front wheel drive for Alfa models above the Sud. Unhappily for us, so began three decades of changes in ownership, mismanagement, inconsistent product planning decisions, disastrously expensive development programs that produce little result, and a belated entry into the booming SUV market.

Still, in the mid-1990s the new front drive Spider and GTV offered hope and in ‘97 Alfa returned under Ateco, who could also see that the soon-to-be-released 156 and coming 147 offered huge potential. The arrangement with Ateco lasted until 2016 when the new formed Fiat-Chrysler group took over.

The high-points in this period were the 156 – Alfa sold 680,000 across its 10-year life cycle from 1997 to 2007 – and the closely related 147 – 652,000 traded between 2000 to 2010. So taken was Audi with the beautiful 156 that the designers were direct to move from Audi’s traditional horizontal grille to a vertical layout. Based on the appeal of the 156, Ferdinand Piech, CEO of the VW Group, decided he must have Walter de Silva, Alfa’s passionate design boss. Eventually, de Silva become VW design supremo. Moving from his beloved Milan was a wrench, but a rumoured 100percent pay increase diminished the burden.

Over the years Piech then made a couple of futile attempts to buy Alfa Romeo. It was not for sale to Volkswagen.

Replacement of the 156 and the terrific 147 proved problematic. Fiat, in the midst of a short-lived joint venture with General Motors, originally intended the 159 should be built over GM’s Epsilon platform that underpinned cars like the Saab 9.3 and 9.6, various American models and the Holden Vectra and Malibu. Hardly encouraging.

Late in the cars’ development the 159 was transferred to a new GM/Fiat Premium platform, intended for more upmarket cars like Cadillac, Saabs and the successor for the Alfa 166. Jointly developed by Alfa, Opel and Saab you can imagine the cultural complexity of linking passionate Latin temperament, German formality and Scandinavian precision and directness. Predictably, it didn’t work.

Moving the 159, Brera coupe and Spider resulted in attractive models that showed great promise, but were overweight and too expensive to build. So much so that the planned Premium-based Saabs and Opels were quickly discarded. The new Alfa’s engines, the 2.2-litre four and 3.2-litre V6 used GM blocks – the V6s made by Holden – with Alfa heads, but neither was as smooth, as rev-happy or as charismatic as the engines they replaced.

One problem with both engines was the timing chain. Traditionally, Alfa used a twin chain because they were reliable and did not stretch. For the new engines Alfa Romeo decided that they could get away with a single chain. Big mistake for the chains stretched, especially on the fours.

Alfa planned a twin turbo 159 GTA, there were rumours of a V8, but they never happened. Weight was reduced and cost taken out for a facelift, so logically, the 159 should have provided the basis for the next generation. Still, many here can attest to the Giulietta’s spirited character.

But the new Giulietta, switched to the Fiat platform, was only moderately successful with sales of 469,000 over its 10-year produce span to 2020.

The Fiat-GM joint venture ended acrimoniously in 2005….There was more drama to come. In 2014, following the bankruptcy of Chrysler, Sergio Marchionee’s Fiat took over Chrysler. His ambition for Alfa was to match Audi.

Marchionne knew underdone Alfas – like the mediocre Mito and the only-competent Giulietta – based on low-cost Fiat architectures wouldn’t work in America. He also rejected styling proposals for the new Giulia and sent Marco Tencone, Alfa’s design boss and the bloke responsible for the 4C, back to the drawing boards to come up with more beautiful cars.

Alfa set up a secret skunk works in Modena, Italy, to develop a raft of rear drive Alfas, the project eventually to be called Giorgio.

Far from Alfa’s Turin HQ, a small group of engineers based at Maserati and headed by Philippe Krief, ex-Ferrari and former head of dynamics for the Fiat Group, modelling a four-pronged range of rear and all wheel drive models intended to take Alfa back to the USA. The new flagship 2.9-litre twin-turbo V6 designed by ex-Ferrari engine man Gianluca Pivetti.

Marchionne’s new plan, the fifth since his 2010 prediction of global Alfa sales of 500,000 in 2014, was directed by a 150-strong team of product planners, engineers and marketers working at Chrysler’s Alburn Hills complex near Detroit.

The first Alfa to be sold in America since the 164 in 1995, the mid-engine 4C sports car, arrived in 2014. Alfa predicted sales of 2500 a year, but when production ended in 2020, they’d built just over 9000 cars. Alfa’s planned version of the Mazda MX-5 became a Fiat. Only 1000 of the exotic 8C were built. Everything depended upon Giorgio.

The Giorgio architecture, developed at a cost of around $8billion dollars was originally earmarked to be used by 15 models and slated to sit beneath not only Alfas, but also Dodge, Chrysler, Jeep and even Maserati models.

When Marchionne died unexpectedly in 2018, and despite the new Giulia being a marvellous car, Giorgio became yet another unfulfilled Alfa Romeo promise, only ever used for two models: the Giulia sedan and the Stelvio SUV, the other Giorgio proposals – some were tooled – including a Giulia wagon, coupe and Spider, a larger BMW 5-series rivalling sedan were shelved. The result: last year Alfa’s US sales totalled just 18,252 and a pathetic 55,000 globally, a far cry from 2001 when over 205,000 cars were sold.

Alfa became one of 14 brands – don’t ask me to list them all – when Fiat-Chrysler merged with PSA in 2021 to become Stellantis. New CEO Carlos Taveres insisted the Group’s brands only use four platforms and that they were all electrified, thus ruling out Giorgio.

Speaking recently to Italian journalists, new Alfa Romeo CEO Jean-Philippe Imparato insisted all future Alfa Romeo models would use the Group’s STLA large-vehicle architecture instead of the Giorgio.

Under Imparato, Alfa Romeo is preparing a renewal of its line-up by the middle of the decade and claims Alfa, “has the potential to be the global premium brand of Stellantis”.

With Alfa Romeo’s sales on a dramatic decline and its existing models, the Giulia and the Stelvio SUV, already in the latter half of their planned seven-year cycles, Imparato is looking towards a newly developed range of hybrid and pure-electric models to drive growth.

He says the line-up will include successors to both the Giulia and the Stelvio, and a new GTV and Spider. Imparato alluded to the Alfa Duetto and T33 Stradale as reference points for future sports cars…We can but hope.

By 2025, just one Alfa Romeo model, the new Tonale compact SUV, will use an FCA-developed platform. The rest will be based around one of three passenger car platforms originally developed by the PSA Group and made available to Alfa Romeo by Stellantis, giving the Italian brand access to pure-electric drivetrains.

Alfa Romeo will continue to operate in close company with Maserati. The two Italian brands will pool more areas of their engineering and development activities as well as sales and service operations in moves aimed at improving their exposure in key markets.

The first Alfa Romeo model to really benefit from Imparato’s leadership will be the firm’s upcoming third SUV, known internally as Brennero. Set to be produced alongside successor models to the Fiat 500X and Jeep Renegade in Poland from 2023, it will form the future entry-level point to Alfa.

Brennero is based on a PSA-developed platform, now known as the STLA Small, which underpins a wide range of models, including the Citroën C4, the Peugeot 2008 and the Vauxhall Mokka that can house multiple powertrains, so the Brennero will be offered in both combustion-engined and pure-electric forms and is set to become Alfa Romeo’s first electric production model.

Key to the plans laid out by Imparato is the adoption of the STLA Large platform. Initially developed by fellow Stellantis brand Peugeot, it will be used for all future premium Alfa Romeo models as a replacement for the Giorgio platform.

This will allow Alfa Romeo to offer mild-hybrid and plug-in hybrid variants of future models, seen as vital to growing sales and a return to profitability within the context of increasingly tight emission regulations in Europe.

Also under consideration as part of Alfa Romeo’s 10-year revival plan is a successor to the Mito which ceased production in 2018. Insiders suggest that it’s likely to be twinned with the next Lancia Ypsilon, building off the same platform as the Brennero.

By 2027, the last internal combustion engine-powered Alfa Romeo will leave the lineup, making Alfa’s EV-exclusive lineup the first of Stellantis’ brands to be fully electrified.

Does Alfa have a future? How can I end on a positive note?

For decades Alfa Romeo was Italy’s answer to BMW, a company that made technically innovative, stylish and dynamic cars.

The only problem: it’s been around forty years since the ‘good old days.’

The dilemma for Alfa Romeo: it can’t hope to match BMW, Benz and Audi model-for-model. The dealer body is weak everywhere compared to the glass and steel cathedrals of the German opposition. Impartaro needs to think outside the box and come up with a strategy that will make Alfa a compelling alternative in what is a crowded luxury-car class.

His team should be brave, try something radically different and stop attempting to compete with the Germans head on. Could a better target be Tesla, a smaller, more boutique brand with a loyal and passionate following, rather like Alfa Romeo used to have.

With Alfa Romeo now just one cog in the larger Stellantis machine, bigger brands like Peugeot, Opel and Jeep must focus on volume, while the Italian brand puts its energy into making exciting, beautiful cars that hark back to its glory days.

Models like an all-electric trio of a GTV and Duetto and like a bigger, better, battery-powered version of the 4C. Given the flexibility of EV platforms, you could build all three off the same architecture and use the same powertrain technology.

In the short term this may not be the most profitable plan, but it’s a vision and that’s something that is crucially important for a brand that’s 112 years old and has struggled for the last four decades.

No matter what Alfa Romeo does under Stellantis, it must follow a strong strategy that, unlike the last few grand visions, is actually followed through on. Otherwise, this once-great marque will face an uncertain future.

Thank you listening.