by Kooverji Gamadia

– – –

If the India of the Raj was identified with the Maharajas and their Rolls-Royces, Bentleys and Daimlers, then independent India was identified with the Hindustan Ambassador, fondly known to two generations of Indians as “The Queen of Indian Roads”.

There was no whiff of royalty about her, quite the opposite, she was about as plebian as a car could be. She could be seen all over India, from the Himalayas to Kanyakumari, the southern tip of India where three oceans meet. She was daily transport and holidays for the urban, upper-class Indian family, a symbol of pre-liberalised, socialist, India. She was temperamental, stubbornly refusing to move at the worst of times, she had a knack for taxing patience to the limit, and she had quirks that the owner learned to deal with, quirks peculiar to each car. She ferried the latter-day rulers of India, as once the Rolls-Royces and Daimlers had carried the representatives of the Raj, with the mandatory red beacon atop the roof to convey its “authority” to the masses, and always in white livery. She thrived during the License-Permit Raj (of which more later) which prevailed from the late 1950s to 1991, the year of its unceremonious discarding, setting a global record for a car produced for the longest time – 56 years – from the same production line.

She met her Waterloo in a very different India to which she was completely unaccustomed, a liberalised India, at the hands of international car giants: Suzuki, Toyota, Honda, Skoda, VW, Hyundai and their ilk, and in 2014, she called it a day, sadly then unsung, but now evoking nostalgia in the generations she served so well. She had character, unlike the faceless modern cars which unsentimentally and rudely pushed her off the road. Her instant recognition by a generation that had never seen the old, socialist India, is testimony to her entrenchment in the Indian psyche.

In order to understand the Hindustan Ambassador and her longevity, it is imperative to understand the cultural milieu in which she thrived. In this essay, I’ve endeavoured to convey that context, rather than a recitation of her technicals,

GENESIS

This, then, is the story of the Ambassador. Derived from the English Morris Oxford Series 11 and first known as Landmaster, it became the Ambassador in 1956, ceasing production in 2014. How and why the Ambassador enjoyed such a lengthy production run requires a diversion into Indian automotive history.

Prestigious marques such as Rolls-Royce, Bentley, Daimler, Lagonda, Hispano-Suiza, Chrysler and Cadillac catered to the Maharajas and upper classes of British India, while marques such as Buick, Chevrolet, Oldsmobile, Studebaker, Austin, Morris and Standard were aimed at minor royalty, the wealthy business and land-owning classes, and professionals. All these cars were imports. General Motors and Ford were the first to establish plants for assembling knocked-down imports for sale locally by the late 1920s. GM’s Buick and Chevrolet marques were particularly popular. American cars with their soft suspensions and simple, robust builds, were more suited to the poor roads than British and Continental cars. British manufacturers for the most part did not establish plants because the Indian market was captive to British products. Sales of cars grew (although no reliable numbers exist) and are believed to have been somewhere around 15,000 units annually in the 1930s. Car production was interrupted with the advent of World War II and the local American plants turned to wartime production supplied to the Allied Forces.

Two prescient Indian industrial pioneers foresaw that the war’s end would ring in stupendous changes in the world order and sought to prepare for the aftermath. In 1942, the Birla industrial group incorporated Hindusthan Motors Ltd, later modified to Hindustan and, in 1948, opened a plant at Uttarpara, north of Kolkata [Calcutta]. A little earlier, the Walchand group signed up with Chrysler. By 1949, Walchand’s Premier Automobiles Ltd was assembling Dodge, DeSoto and Plymouth cars as well as Chrysler’s trucks and some Fiat models. A variety of collaborative ventures between Indian companies and Western automakers sprouted, the best known being the venture between India’s largest industrial group, the Tatas, and Daimler-Benz, which completely altered the Indian trucking scene with their Tata-Mercedes-Benz badged trucks. Although the collaboration ended in the 1960s, the enduring legacy of the Benz name in India induced Daimler, which re-entered India in the mid-1990s, to badge their locally made trucks Bharat Benz instead of Mercedes-Benz.

The end of the War unleashed global social and economic changes, to which the Indian automotive scene was not immune. Britain withdrew from India in August 1947 after Partition. The new Dominion of India was immediately engulfed in a moiety of problems: the huge transmigration of 12 million people across the subcontinent, and war with Pakistan. The new government of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru deemed motoring a non-essential activity.

In 1951 the Government introduced the Industries (Development & Regulation) Act, which sought to create a Soviet-style planned economy. This meant a license was required to establish a new factory or expand production/product mix in an existing factory, when the production was of items deemed to be of national importance. This policy, later notorious as the License Permit Raj, dissuaded foreign investment, and actively hindered India’s industrial development until it was dismantled in 1991. Import duties on foreign goods were simultaneously raised, which resulted in foreign automakers, including GM and Chrysler, exiting India by the end of the 1950s. What remained was an India in which almost everything was perniciously rationed, including basic foods such as rice, pulses, and cooking oils, which one could buy at ration shops. Shortages of milk and butter were common, cheese was unknown to the masses. Suffice to say that the situation was not very different from that in the USSR, and may be best described in the words of Dr Chidambaram, former Union Finance Minister and Home Minister, penned in the Indian Express newspaper of 5 January 2025, “The present generation (born after 1991) scarcely believes that there was an India with (only) one television channel, one car, one airline, one telephone service provider, trunk calls … and long waiting lists for everything from two-wheelers to train tickets to passports.”

The economic reforms initiated in 1991 by then Finance Minister Dr Manmohan Singh unleashed the latent potential of the Indian economy to startling effect.

It is against this backdrop that Indian motoring must be seen, a monochrome period that lasted from the early 1950s till the reforms of 1991, during which only three indigenous automakers monopolistically thrived: HM, PAL and Standard Motor Products of India Ltd. PAL made the Fiat 1100 (Premier) in its various models until the early 2000s. Standard Motors produced various Standard-Triumph models but died out by the late 1970s and was wound up in 2006. With car production throttled by the 1970s, waiting lists to buy a new Ambassador or Premier were as long as seven years. It is this scarcity factor that accounted for the Ambassador’s long production run.

These halcyon days were not to last. In the early 1980s an upstart called Suzuki entered into a joint venture with the Indian Government called Maruti-Suzuki Udyog Ltd and completely transformed the automobile industry. Suzuki’s modern cars, then badged as Maruti, were produced in far greater numbers, to meet demand. Nobody wanted the stodgy, out-of-date Ambassador or Premier. The Ambassador survived as the vehicle of choice for Government until it too fell under the onslaught of international automakers who entered India starting in about 1995. These included GM, Ford, Mercedes-Benz, BMW, Audi, Skoda, VW, Fiat, Daewoo, Hyundai, Kia, Toyota, Honda, and even the Chinese BYD. In the midst of this turmoil, the role of the home-grown Tata Motors Ltd, a market leader in many segments especially EVs, ought not to be overlooked. When India opened up international brands could sell you a car on the spot (instead of a seven-year waiting list), which sent Ambassadors to the scrap heap because everyone flocked to buy the latest cars.

THE BIRTH OF THE HINDUSTAN AMBASSADOR

In 1949 HM, recognising the need to cater to two segments of the Indian market, namely big cars for the upper classes and small cars for the middle classes, signed two agreements with Studebaker and Morris. Soon, Studebaker’s Champion was being locally assembled, selling well into the upper classes. In England, Morris re-introduced the pre-war Morris Ten, which HM made locally renaming it the Hindustan Ten, and fitted with a Morris 1.1-litre engine. In 1950 the Morris Minor replaced the Ten. In 1956 the Morris range was complemented by what was to become the most famous of all Indian cars: the Morris Oxford Series II, renamed Hindustan Fourteen, fitted with Morris’s side valve 1.5-litre engine. The Minor cost Indian Rupees 8,025 and the Fourteen Rs 10,085 (roughly £500 and £630, respectively at the prevailing exchange rates). By comparison, Studebaker Champions sold for about Rs 12,000 (about £750).

THE REAL AMBASSADOR

When Morris introduced the Oxford Series II in England, HM replaced the Hindustan Fourteen with the Series II in 1954, renaming it the Hindustan Landmaster, and carried over the side valve engine from the Hindustan 14/Oxford MO. Morris then introduced the Oxford Series III in 1956. Upon cessation of production in England in 1959, HM bought the tooling and started producing the venerable Hindustan Ambassador. It would survive from 1959 until 2014.

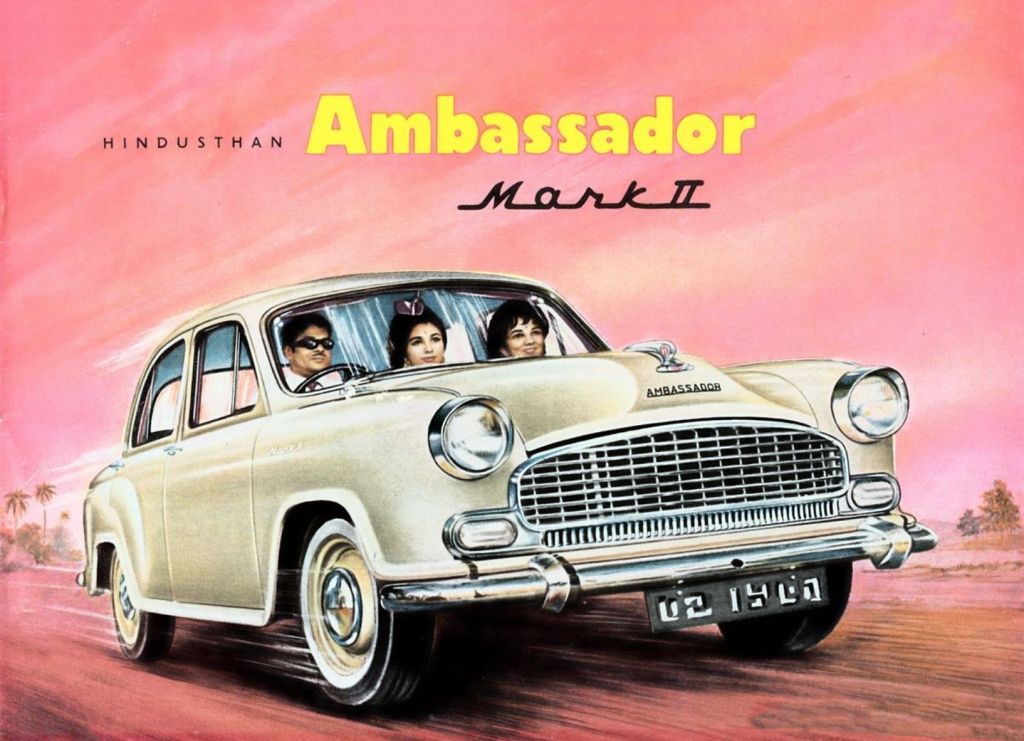

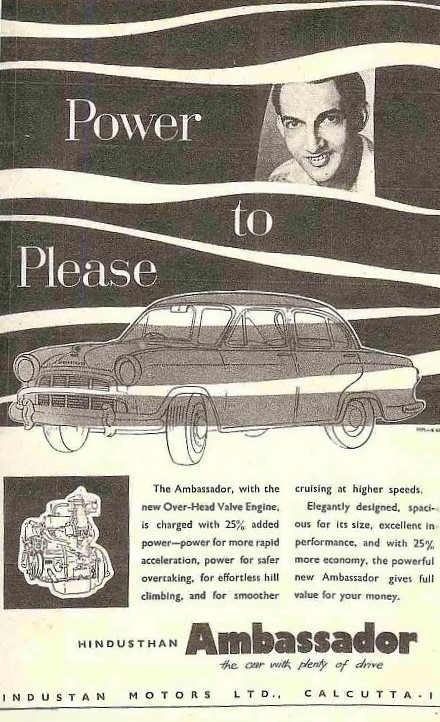

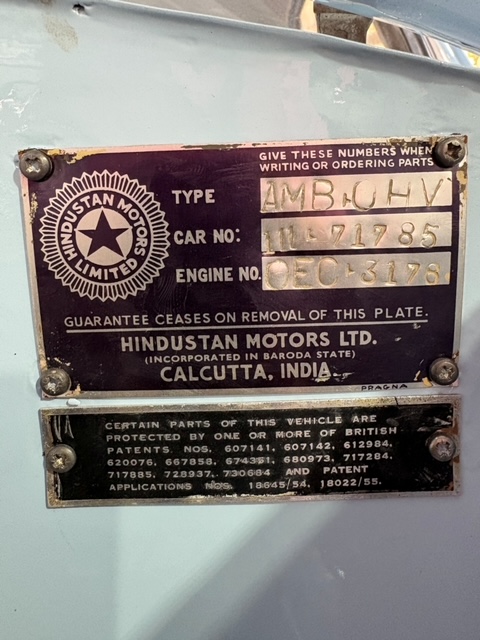

The Ambassador started its life with the same 1.5-litre side valve engine used in the Landmaster, but by 1959 adopted the BMC B-series ohv engine. These later cars proudly sported the O.H.V. badge. In 1962, the O.H.V. underwent a minor facelift of a new grille, side lights and bumper guards, and was called Ambassador Mark 2. The older side-valve and O.H.V. cars were retrospectively termed Mark 1. The Mark 2 was produced from 1962 to 1975 when it was replaced by the Mark 3, then the Mark 4, and other variants, some with Isuzu petrol and diesel engines.

Call me pedantic, but I do not consider the versions produced from 1975 to 2014 to be real Ambassadors.

Why, when they appear to be essentially the same car? Because they use an Isuzu engine. I suspect that only a few Ambassador enthusiasts feel this way, while the rest of the population lumps them all together.

The semi-monocoque Ambassador was roomy, had a simple engine initially fed by an SU electrical fuel pump and SU carburettor but later replaced by indigenous products. Its solid rear axle became notorious for breakdowns. But its overriding virtue was ruggedness, a necessity for Indian conditions, accompanied by simplicity, which allowed roadside mechanics to repair the car. The gauge of steel employed in its construction resembled that in naval light cruisers. It was the car of choice for upper-class families in those austere times when imports were not permitted.

Those were the years when India was building her heavy industrial base, such as steel and power plants, oil refineries, and dams which Nehru called “The new temples of India”. Foreign exchange reserves were scarce, foreign travel was severely restricted, and in general, severe import restrictions were in place. The Government’s dicta to industry was to indigenise in order to conserve foreign exchange, and by the early sixties, the Ambassador began the first of its many transformations from its English parent. Owing to the scarcity of parts, HM was known to mix parts in individual cars as they became available. A collector friend of mine told me that an Ambassador Mk 2 bought in 1969 had the SU carburettor whereas the one bought in 1973 had a Solex. Smiths dials, originally calibrated in miles were gradually replaced with ones in kilometres in the sixties, and starting about 1967 by locally made Yenkay instruments. Despite these born-of-necessity modifications, the car essentially retained its English character until Mark 2 production ended in 1975. The name plate of my Mark 2 lists various English patents to prove the point.

BEYOND THE MARK 2

The Mark 2 was produced from 1962 to 1975, before it was replaced by the Mark 3 in 1975 and the Mark 4 in 1979, with other variants following. Suffice to say that cosmetic changes in the design of grille, lights, bumpers, dashboard and the like continued, with the BMC engine replaced by Isuzu units. Annual sales of some 30,000 to 40,000 during the car’s golden period in the 1960s and 1970s dwindled into nothingness by the early 2000s, until production ceased in 2014. HM sold the rights to the Ambassador brand to PSA Peugeot Citroen in 2017.

During the 1980s and 1990s, the Ambassador rendered yet another service to the public. Petrol in India was priced thrice as much as diesel, causing many old cars such as Ambassadors, the locally-assembled 1950s Dodge Kingsways and Plymouth Savoys, to be converted from petrol engines to diesel engines. The most common diesel engine retro-fitted to the Ambassador was the Matador 2.4-litre engine, built under licence from Mercedes-Benz and from a large van. These converted cars were rough, rattled your bones to the core, and required considerable fortitude to survive long drives. By the late 1990s the advent of international manufacturers with their sophisticated modern fuel-efficient cars rendered this practice redundant.

MEMORIES OF THE AMBASSADOR AND MY MARK 2

I first saw an Ambassador in 1964 when I was six. I now realise it was a Mark 2. I was sitting on the rear seat of our 1939 Flying Standard at a traffic light when a pinkish purple (called Autumn Russet) Ambassador descended on the opposite side of the intersection. Traffic was sparse then, and the oncoming car caught everyone’s eye. I remember my parents commenting admiringly. No one could then foresee the place this car was to hold in the hearts of two generations of Indians.

For most Indians born before 1991, the Ambassador is the one symbol of socialist India etched into their memories, a symbol of the earlier scarcity and austerity. She was the family car, the car that their grandfathers, fathers and uncles drove, the taxi that ferried you to school, or from railway station to home or hotel, the car that took you on holidays, and if you were among the fortunate few, to your bungalow in an erstwhile British Hill Station. She was simplicity itself, with lots of spare space under the bonnet and none of the congested clutter and maze of pipes and cables that infest the engine bays of modern cars. She had no pretensions to sophistication, and none of the bells and whistles so beloved of modern cars. Her gears were hard and regularly produced gnashing and growling sounds during gear shifts, her right-slanted steering called for strong biceps, and her brakes almost called for you to stand on the brake pedal. The standing joke was that everything made noise except the horn.

It was the car that dutifully blew its cylinder head gasket in the middle of nowhere, with dad cursing under his breath and being forced to hitch a ride on a passing lorry to fetch the nearest mistry (mechanic). Mum wondered whether he could repair a bicycle let alone a car, while she laid out the durrie under a tree by the roadside and spread out sandwiches, biscuits, patties and lemonade while the mistry worked his magic.

In his piece on the Ambassador in the Times of India, 10 October 1999, long-time BBC India correspondent Sir Mark Tully describes the Ambassador’s contribution to the creation of a quintessentially Indian “vehicle recovery system … which is far more efficient than the service networks set up by the new manufacturers and a lot cheaper too. Almost every village on a main road has its misteri or mechanic who knows the Ambassador like the back of his hand. The misteri is a master of improvisation never stumped by a lack of spare parts. If you can’t get the car to him, he will come over to you and repair the car on the spot”.

In his book Rambles and Recollections of an Indian Official, Col. Sleeman describes his adventures in 1800s India. Indian road trips in those days were adventures of a not-too-different kind, complete with the dacoits (bandits) described by the good Colonel, for which you prepared by carrying an extensive tool kit and a whole host of spares, including but not limited to fan belt, starting handle (most useful for installing a new fan belt), condenser, contact breaker points, spark plugs, hoses, thin wire, towing cable or rope, not to forget jerry cans of water, because the Ambassador could be relied upon to throw tantrums sometime somewhere, and it paid to be an amateur mechanic, a situation eloquently summarised by Sir Mark, “The Ambassador’s aerodynamically unfriendly, rounded, bowler-hat roof, and its unfashionable high gait, recall the gallant days of motoring when drivers never knew whether they would reach their destination without a breakdown”.

Among the old lady’s quirks was a stubborn refusal to start in the mornings after a heavy tropical downpour. You then hastily removed the spark plugs, roasted them in a fireball of cotton waste soaked in petrol, re-installed them, and had the satisfaction of seeing the old lady spring to life. Every now and then, the mechanical fuel pump, located near the exhaust, took a holiday. You coaxed it back to life by jacketing it in water-soaked cloth until it cooled down. A more permanent solution was to encase the fuel pump in the two halves of a coconut shell, an insulation technique more effective than the best materials devised by the American space program. A packet of turmeric powder, poured down the radiator, sealed leaks in the cooling system.

Those were the days of a kinder, gentler, unhurried time, during which you dutifully gave hand signals before turning (turn semaphores and flashers were rarely used), gave way to ascending vehicles on hills and to traffic on your right at roundabouts, graciously allowed a car from a side lane to enter a main road, did not madly honk and curse loudly while a stalled car was being pushed to the side of the road.

The Ambassador was also adept at providing other forms of employment. I recall a monsoon day in the late 1980s as a passenger in a friend’s Mark 2 in a flooded street in Kolkata. The Ambassador dutifully exhibited one of her quirks: ingress of flood water into the distributor. As the car stalled in the centre of the road, a waiting horde of small boys rushed towards it and for a small pittance pushed it to terra firma.

Buying an Ambassador in India was an experience in itself. In about 1993, a colleague and I journeyed the 150km from Cochin to Coimbatore to take delivery of two company-ordered Isuzu-powered Ambassador Novas to drive them back to Cochin. We’d been assured that both cars were ready for delivery. To our dismay we found one Ambassador with its engine half-opened on the shop floor and with a dented and scratched body. The dents and scratches were more glaring on the other car. The dealer apologetically told us they were unavailable for immediate delivery. In those times, cars were driven from the Uttarpara factory to their destinations, typically hundreds of kilometres away. Braving Indian roads meant they generally required attention upon reaching their destinations before delivery to the customer.

I was witness to one of the reasons for the Ambassador’s longevity. In the 1980s, one of the largest steel companies in India replaced the Ambassador as the company car in its iron ore and coal mines in Eastern India with a locally made version of the Rover SD1 (badged the Standard 2000). Even though the car was modified with a higher ground clearance for the Indian market, the Rover was unable to cope with the rough rural roads which presented no obstacle to the Ambassador, while its repairs were outside the scope of any vehicle recovery system, resulting in Rover’s hurried phasing out, and the Ambassador’s triumphant re-entry.

In recent years, the introduction of an Indian Heritage Class in car shows has sparked a resurgent demand for India-made cars. Since most older cars were either scrapped or converted to diesel or otherwise modified, original Landmasters and Mark 1 and Mark 2 Ambassadors are rare, and increasingly sought after. I looked for years before I found an unmodified Mark 2, which belonged to a retired Indian Air Force officer. The car which had been laid up for a decade, came in her original Royal Ivory, was flat-bedded down to Mumbai and with a little attention, became operational. I used her for some months, receiving appreciative gestures from passers-by and fellow motorists who even took photographs and videos of this relic from a bygone age, before deciding to send her for a complete restoration.

* * * * *

(I am greatly indebted to Mr Gautam Sen for his knowledge and his book “The Automobile, An Indian Love affair” for many of the facts and figures contained in this story, and to Kartik Aiyar and Karl Bhote for allowing me to use photographs of their Ambassador Mark 1 and Landmaster.)