Few travelling companions were as stimulating as Anatole ‘Tony’ Lapine, the Latvian-born American who ran Porsche design from 1969-1988 and died in late April, 2012, just weeks after the death of his predecessor Butzi Porsche.

Tony and I were two of a disparate group of journalists gathered together by Automobile Magazine in the week before the 1993 Geneva show. Our task was to compare five ‘world class’ and favourite American cars on European roads. Tony’s writing task was the Ford Explorer, a vehicle he quickly came to despise. “To embrace this dressed-up truck, Europeans would have to forget what they know about vehicle dynamics. Don’t count on it,” he wrote. “I don’t like things that are ‘good enough’ and I particularly do not like seeing a great company like Ford working so far beneath its capability.”

Over a copious dinner one evening Tony, fluent in at least four-languages, told us how he came to join Porsche. Lapine working in Bill Mitchell’s notorious, secret Studio X at General Motors, where he contributed to the gorgeous 1962 Chevy Monza GT concept and was studio engineer for Japanese-American Larry Shinoda on the gorgeous ’63 Corvette Sting Ray, The modeler was Italian Chester Angeloni and the three were affectionately nicknamed the “AXIS POWERS” as they worked directly for Bill Mitchell. According to Lapine, Shinoda would occasionally come into the studio and yell out…”Bill’s (Mitchell) not here today” and the team would depart for lunch with Larry driving like hell to Woodward Avenue to an Italian restaurant for the longest liquid lunch.

In 1965 Lapine was transferred to Opel. Following a chance meeting with members of the Porsche family in 1968, he invited them to visit Opel to see their new design studio. Chuck Jordan, the American design chief at Opel, was hugely impressed that a group of old world Porsche executives, including Ferdinand Piech, FA Butzi Porsche and Ferry Porsche would be interested. The Germans arrived. Not as expected in a fleet of 911s, but an enormous air-conditioned Pontiac wagon.

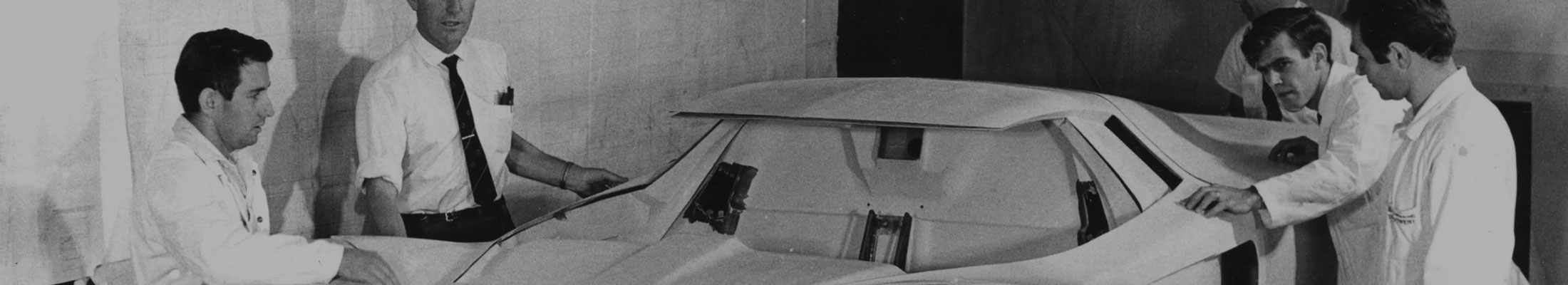

A few weeks later, Lapine was approached to join Porsche and in 1969 he and four colleagues left Opel to form the foundations of Porsche’s new design studio. Jordan was not impressed. A little later Porsche built a new design studio, inspired by the Opel facility. These men Dick Soderburg and Wolfgang Mobius, modeller Peter Reisinger and engineer Jurgen Mayer, plus Lapine, formed the core of the team that designed both the 924 (with Harm Lagaay) and the 928, though in separate studios so one could not influence the other.

Initially, the 928 package called for a car a little longer in wheelbase and length and slightly wider than the 911, yet with two plus two seater. Problems arose when they realised the Mercedes-Benz automatic transaxle forced a dramatic blow-out in width. Under Lapine’s leadership, the designers disguised the 928’s vast width – it ended up being 186mm wider than the 911 – to create Europe’s first ‘soft’ production car, a hugely influential design that was copied and recopied for two decades and, significantly, never replied on any 911 design cues. It is a tribute to Lapine’s eye that the 928 looks smaller than it really is. Approach it from three-quarters front or rear and, because of the extreme taper at each end, there appears to be virtually no overhang.

Tony also oversaw creation of the G-model 911 and was responsible for the 964 911, the body virtually all new, yet little changed visual. Tony claimed it was not the car he originally planned to design. By the late 1980s, his heath feeling the pressure of the job, Tony was gently edged out of Porsche to be replaced by Harm Lagaay. Erudite, charming and a great story teller, the timeless 928 ensures that Tony Lapine also leaves a giant design legacy.