by Peter Robinson

Nine months before the launch of the 996 – the first water-cooled 911 – I attempted to arrange an interview with Butzi Porsche, designer of the original air-cooled 911 and son of Ferry Porsche. That was February 1997. However, my attempts to set up a meeting with Butzi at Porsche Design, his independent design consultancy based in Zell am See, Austria, elicited just silence. It was only after Porsche Public Relations boss Anton Hunger interceded and spoke in favour of my interview with Mr F.A. Porsche (as he was always known in Zuffenhausen), that we finally settled on a date in April.

There were, however, two provisions. I was to submit written questions beforehand “so F.A. can prepare himself” and Michael Schimpke, Porsche’s foreign press boss, was to sit in on the interview. No bad thing, as I discovered. Butzi, an inherently shy man, preferred to have his native German translated in to English, with Schimpke acting as simultaneous translator.

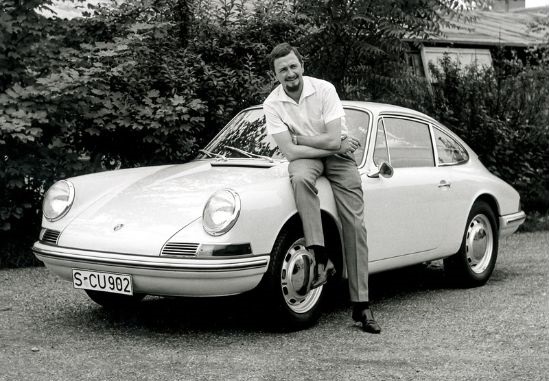

I arrived just before noon on Thursday April 17, 1997, at Porsche Design’s minimalist glass two-storey HQ to meet Ferdinand Alexander Porsche III – Butzi to the world at large – to interview the man who created the apparently timeless 911 shape. Ironically, though no one knew it in the early ‘60s, the 911 was the last car designed solely by the obviously talented F.A. Porsche, who died on April 5, 2012.

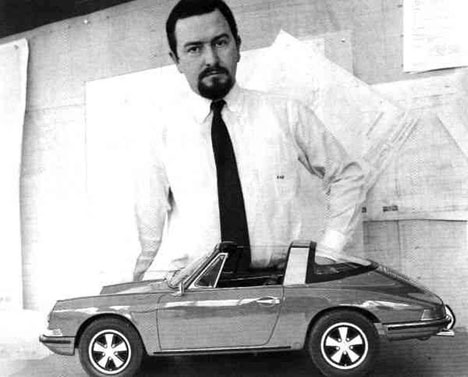

After Butzi, and his brothers and cousins (including Ferdinand Piech) left the family company – Ferry and Louisa, Ferdinand Porsche’s children, wanted to avoid the growing internal family feuds and banned all family members from holding managerial positions within the company – he started Porsche Design as an independent design studio in 1972. His first object was the famous Porsche watch, but he also worked on furniture, lights, sunglasses, cameras, trains and even pipes.

We met in the conference room of Porsche Design’s chalet studio in Zell am See, in the Austrian Alps. After a few questions (all from my list) Butzi seemed to approve and we moved to his far more personal office, with its views of the lake and snow-capped mountains, that was to remain his favourite workplace until he retired in 2005.

Formal to the point of being retiring, yet still friendly, Butzi didn’t come across as a designer in his suit, handkerchief in the jacket pocket, and tie. In the shelving behind his desk were dozens of model cars, books on design and the history of Porsche, and a row of motoring badges, while the walls were lined with photographs, including two of the 911. There was even a drafting board. “It’s a source of mirth to those who work with computers,” he said, smiling “but I need it for ideas and inspiration.”

Most prominent among the models were his favourite Porsche – the 904, the 1963 mid-engine racer he designed – plus an early 911 and the 1993 Boxster concept. Others included a Citroen 2CV, Morgan +4, Duesenberg Model J, Cord 812, an early Ford Mustang and a ‘20s Rolls-Royce. Why these?

“They all caught my attention,” he said. “Not necessarily for positive reasons. Most have natural, classical shapes that appeal to many people. I wanted to create something with the same harmonious elements.

“Good design should be honest and functional.”

Butzi Porsche was born in Stuttgart in December 1935, at a time when his grandfather was engineering the VW Beetle for Adolf Hitler. After the allies began bombing Stuttgart during WWII, Ferry Porsche decided to move his four sons to the Alps and the children transferred to Zell am See in 1943.

“We left all our toys behind,” Butzi said. “In Stuttgart we could afford anything we wanted: now we had nothing. We were left to our own devices and our imaginations. There was a glider field in the town, so we made cardboard gliders that really did glide.”

Butzi went to a private Rudolf Steiner school, “where my creativity wasn’t stifled” and learned basic craftsmanship in metal, wood and stone. He was apprenticed to Bosch as a machine engineer and three years later, in 1957, he spent six months at the Ulm School of Design. Finally, in 1958, the young Porsche joined the family company.

At the time, Porsche’s tiny design department was run by Erwin Komenda, who had worked on the Beetle with Ferdinand Porsche and, later, helped style the 356. Butzi’s first design task at Porsche was to build wooden 1:5 scale models for testing in a Stuttgart wind tunnel. “The creativity was in the models and from these we did the (drafting) drawings,” he explained. “It was the opposite of the normal process, in which the drawings come before the models.”

Years later his father said, “Butzi soon showed a remarkable talent for styling.” As Porsche’s 1962 F1 car and the beautiful 904 (officially Carrera GTS) proved. Working within the strict limitations of the sports car regulations – that basically set the dimensions – Butzi and Porsche’s racing department had just four months to create the 904. The time constraints meant that Butzi’s original design was left unaltered by the engineers; clean, pure and delicate of style.

The origins of the 911 began with the idea to build a four-seater 356 Cabriolet. Butzi concedes that this much bigger 356 didn’t work.

“The funny thing was,” Butzi said, “that if we did a four-seater, everybody wanted a two-seater and if we designed a two-seater, they wanted a four-seater. The idea was not so much a new car, but how to change the 356.”

Butzi’s first interpretation of a car to replace the 356 came with the Type 754 T7, built on a wheelbase of 2400mm and intended as a four-seater. The first 1:7.5 Plasticine model was completed on 9 October 1959, two months before his 24th birthday.

“I recorded my ideas in rough sketches, in part so that I had better control of the lines, but then quickly translated everything to the model so that I could better visualise the shapes.”

A full-scale model was finished on 28 December 1959. Apart from a wrap around rear window, it is the 911. Then Ferry decided the new car should be more sporting by reducing the wheelbase to 2200mm (the 992’s wheelbase is 2450mm). Butzi’s design was immediately selected by the board and soon after, in 1961, Ferdinand III was appointed head of Porsche’s ‘model’ department.

The 911 reduced the curves of the 356, presenting a more solid, yet minimalist appearance, while trimming the bright-work back to a minimum. I asked why the 911 has survived for so long – remember this was 25-years ago in 1997 when the 911 was just 34-years old – Butzi paused. “It is my father’s idea that a car should not be ostentatious, nor too aggressive; the shape should be harmonious yet also have presence. The 911 has balance; it is also small. There is a modesty about the car that makes it notable. Good design is where you don’t force things into success or recognition. Catch a glimpse of the silhouette and you know it’s a 911.”

Would he still like to be designing Porsches? “Yes,” he said, his voice tinged with regret. “But I respect the wishes of the family not to operate in the business.”

Any thoughts on the then-new Boxster? “I like the shape, but there is too much James Dean Spider about the car generally. I find the form of the rear lights unacceptable. Form used to follow function: form is too dominant today.”

Ten years earlier a major Japanese car maker asked Butzi to design a sports car. He refused. “I am too close to Porsche. I just didn’t want to do it.”

After Butzi’s death, Porsche issued a long and emotional tribute to the man, quoting him as saying:

“Design must be functional, and functionality must be translated into visual aesthetics, without gimmicks that have to be explained. A formally coherent product needs no embellishment, it should be increased by a mere formality. The form should be presented to understand and not distract from the product and its function. Good design should be honest.”