Readers of this column undoubtedly know of Borgward, but I suspect most people under the age of 50 have never heard of the marque, let alone acquired any real knowledge of the German cars. Yet, for a short time in the second half of the 1950s, the Borgward star shone brightly, before vanishing almost overnight, burnt out in an unnecessary plunge into insolvency that could surely have been averted.

By the end of the decade, Carl Borgward’s Isabella had become a favourite of both rally and racing drivers, enthusiasts, road testers and the general public, all of whom respected and even treasured its unique combination of virtues. There was nothing quite like it then, and there really isn’t any car today that unites the same fine qualities. Probably BMWs from the 1980s and 1990s, when they really were the Ultimate Drive Machine, came closest.

Of the Isabella, Doug Blain, wrote in Wheels (March 1959), “This, friends, is what a family car should be. If there’s a single manufacturer with interests in Australia who hasn’t already taken an Isabella to pieces then we advise him to get cracking….In matters of cornering, stopping and weight-for-age acceleration she leaves almost every other family car we’ve ever tried for dead. And in her price and interior space class she’s just about unbeatable value for the man who appreciates fine basic engineering and go-ahead design.”

Borgward accomplished the seemingly impossible goal of blending a large, five, even six-seat body with a small, 1.5-litre overhead valve engine to create excellent performance and economy. The big body/small engine/high performance philosophy was matched to precise steering, responsive handling and strong brakes. Little wonder that in 1959 38,000 Isabella were sold out of Borgward’s total production of 105,000 cars.

The Isabella first appeared in mid-1954 and was an immediate success. In 1955 Borgward was second only to Volkswagen among German car makers. Obviously well made, the Isabella’s engine used an alloy cylinder head and developed 60bhp, enough for a top speed of 85mph (137km/h). The secret to the strong performance and equally outstanding economy was, of course, the low weight of around 1070kg.

There were other virtues: the contemporary styling meant large glass areas for good visibility, an advanced specification that included all independent suspension, with wishbones and coils at the front and trailing arms and coils at the rear. A four-speed all-synchromesh gearbox was control by a steering column change proving such mechanisms could be made to work properly, for despite slow synchromesh it was precise as well as being a pleasure to use.

Soon there were wagon, cabriolet, chrome laden coupe and even ute versions, though it was the TS sedan, introduced at the 1955 Frankfurt show that really established the Isabella as a minor masterpiece. Few, if any, sedans from this period could match the Isabella. Now developing 75bhp at 5200rpm, its fine handling, high-revving engine produced a 0-100km/h of quick-for-the-period 16 seconds. Moreover, it was a delight to drive.

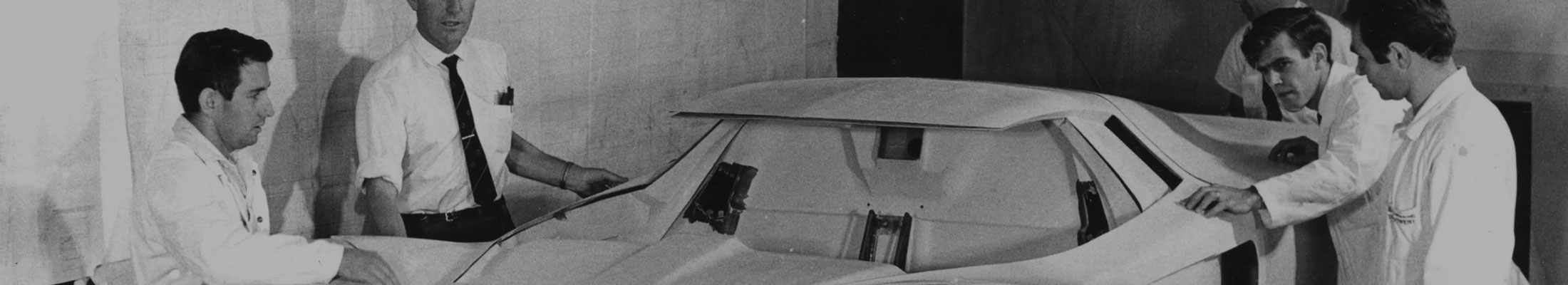

Yet, by July 1961 Borgward was finished and two year later its founder was dead. The replacement Isabella, with its newly designed 1.6-litre engine, never saw the light of day, although its Frau-styled body became the basis for the Glas 1700, soon to be a BMW. In fact some believe Borgward, with any providence at all, could have achieved the huge success of BMW. Ironically, it was to Munich that many key Borgward people went when they left Bremen after the collapse, while the Borgward facility is now owned by Mercedes-Benz and makes C-class variants, the E-class coupe and cabrio, SL sports car and, next year, the EQC electric car.

But what of Carl Friedich Wilhelm Borgward, who created this automotive empire and lost it so easily? Born on 10 November, 1890 in a suburb of Hamburg, Carl was a self-taught man, who left school at the age of 16 to become an apprentice locksmith, before being wounded on the Western front in World War One. After the war he joined a firm which made tyres, but under his influence switched to producing body panels and radiators for Hansa-Lloyd. Borgward rose quickly through the ranks and by 1921 had become sole owner of Bremer Kuhlerfabrick Borgward & Co.

Eager to get into the car business, Borgward designed a two-cylinder sports car, but lacked the backing to get the project off the ground. In 1924 he began building a petrol-powered, three-wheel delivery cart that was sold to the German post-office. Later came a three wheeler with the single wheel at the rear. Somebody recommended it should be called Lilliput, but Borgward reversed the argument to name it Goliath. Inevitably, the expanded range grew to include four-wheel models. By 1930 the newly named Goliath Werke Borgward & Co was so successful it built 10,000 vehicles and took over Hansa-Lloyd.

Then came the first car, a three-wheeler that was to be the star of the 1932 Berlin show. A simple 200cc two-stroke, the Goliath Pionier had a top speed of just 35mph (56km/h) and failed to attract enough customers to justify continued production after only 4000 were made. Borgward’s first ‘real’ car was the Hansa 1100 in 1934, soon to be joined by a series of 1.5-litre four and 2.0-litre sixes. Under Hitler’s car policy, allowing each car maker only selected classes, this broad model line-up was terminated and Borgward was left to produce just 2.0-3.0-litre luxury sedans. World War Two began only months later and spelt the end of car production. Borgward’s plant became an armaments factory during the war, he was interned by the allies for 34 months, not returning to Bremen and his war-torn factories until July, 1948.

Borgward enthusiastically began planning an entirely different approach. Instead of just one car company he would have three: Lloyd, Goliath and Borgward, a clever way to get three times the raw materials allotted to one firm. However, keeping the engineering, styling and sales departments of each company meant excessive duplication at a time when every pfenning counted. This policy even led to Lloyd developing a new water-cooled, 900cc flat four – later to be used by Subaru as a prototype for its boxer engines – when Goliath already had an 1100cc engine of the same layout.

Borgward’s best sales year was 1959; it also saw the release of the P100, the firm’s rival to the Mercedes-Benz 220SE six. Powered by a new 75kW 2.2-litre six, it had Germany’s first pneumatic suspension and was an attractive, powerful sedan. But its development cost Borgward more than money. Shortly after it was released Borgward had to ask the Bremen Senate to lend him money so the banks would provide further loans. This had been a regular occurrence but this year, the ship building yards desperate for men, the old threat of firing his workforce reduced his bargaining power. Germany’s top-selling weekly news magazine got hold of the story and implied that Borgward was too old and his company stumbling.

It was enough. Suppliers credit lines were cut off and the Senate stopped all cash flow. The management consultant that ‘save’ BMW less than a year earlier stepped in, though some believe BMW’s Herbert Quandt did his best to prevent any rescue of Borgward. In the face of the Big Three’s compact cars, US sales plummeted, while warranty claims for the new Lloyd Arabella mounted. The pack of cards was falling. The autocratic Borgward lacked the will to fight the political battles necessary for survival and on February 4, 1961, the Bremer Senate effectively filled off the company, before filing for bankruptcy a few months later.

A cooperative of customers, suppliers and dealers tried to intervene, but the Senate ignored their requests. After building close to 2500 P100s in Germany, the P100 tooling was shipped off to Mexico and around 2000 were produced there between 1967-1970.

Carl Borgward couldn’t understand how his empire could be lost so quickly and died a broken man. In the late 1990s, Carl’s grandson Christian revived the brand and with help from BAIC, the giant Chinese group, introduced a Borgward SUV in 2017. I yet to read an independent assessment of the new Borgward to know if it remains true to Carl’s philosophies.