by Peter Robinson

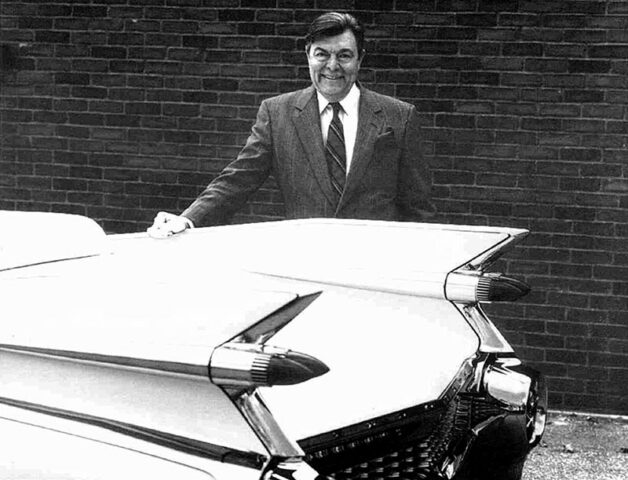

One lunch time in August 1956 Chuck Jordan, an inquisitive, 28-year-old General Motors’ stylist, decided to see what Chrysler was planning for its 1957 models. Jordan drove to the back of Chrysler’s Hamtramck assembly plant, a few miles across town, to get an advanced look.

“I used to go past there because I was anxious to see next year’s cars before anyone else,” Chuck told American automotive historian John Lamm. “There, through the chain-link fence, I saw all the brand new 1957 Plymouths. Wow, that was a real shock. They looked so clean and lean with that thin roof and nice proportions of glass: All just the opposite of what we were working on at GM at the time.”

“All I could see were fins, fins, fins,” Jordan told me years later, recounting the story. He immediately alerted his boss Bill Mitchell and together a small group of designers drove over to see the spectacular all-new Plymouths.

It was to be a turning point. Under Harley Earl’s 30-year reign as design boss, General Motors established design leadership and with it market domination. In an era when the annual model change largely dictated sales, GM simply out-styled its rivals. But by 1956 many at GM, including President Harlow Curtice and Mitchell, began to feel the once all-powerful Harley had lost his way. The 1957 Chrysler cars proved it.

It was too late to do anything about GM’s 1958 models – with their power-dome hoods, thick, heavy midsections and lashings of chrome – but with Earl away in Europe on his annual motor show tour, Mitchell was brave enough to start again on the ’59s as GM sought to re-establish its position as the styling pioneer with a series of individual designs of its own.

GM’s initial proposals for 1959, heavily based on the 1958 models, delivered more of the same. Earl was still pushing, “These low, massive chrome bumper bars, big roofs and thick cars”, epitomised by the 1958 Oldsmobile and Buick. Jordan told me how, for the baroque ’58 Olds, “Earl picked up the theme of the front and wanted it on the side. ‘You put all of this on.’ Harley demanded. Earl added, ‘and I’ll take off whatever I don’t want. ’” Except he never took anything off and the car was a chrome-plated disaster, the two side brightwork themes being completely unrelated. When Earl saw styling’s proposal for the 1958 Buicks, Harley Earl ordered designer Stan Parker to “add 100 pounds of chrome; that’s only 80 pounds. Put on some more.”

“As young designers we were depressed,” Jordan said. “We were about ready to quit. We couldn’t live with those heavy cumbersome cars.”

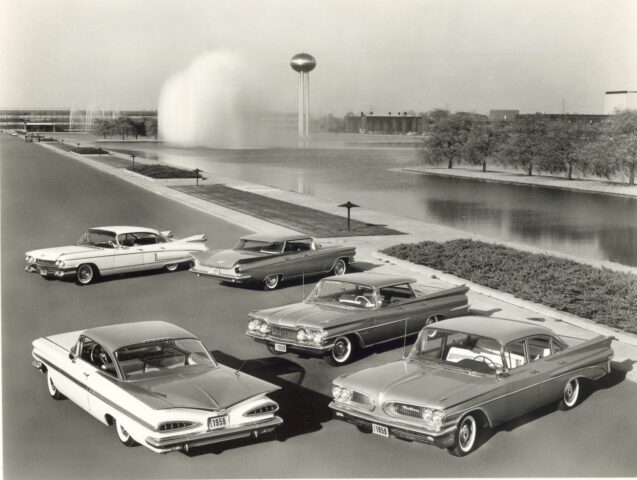

Effectively, those early 1959 models marked the end of Harley Earl’s regime. The palace revolt led to new ideas – some wild and too far out – while others were adopted: thin roofs and roof pillars, vast glass areas with ‘flying wing’ roofs on the four-door hardtops, gullwing fins on the Chevrolet and Buick, and the Cadillac’s super tall fins. Staggeringly, the redo meant that Chevrolet and Pontiac’s 1957, 1958 and 1959 models where all new, apart from their drivetrains.

According to Jordan, “When Earl returned from Europe he came into the studios, saw the new 1959 models, looked around, and walked out. Didn’t say a word. A couple of days later, Mitchell told us Earl had decided to support the second design.”

GM’s flamboyant 1959 models meet with mixed results. On November 22, 1958 Harley Earl, the father of car design, took mandatory retirement at 65 with Bill Mitchell his successor.

Jordan scored heavy with his work on those new 1959 models. Already in the GM fast lane, he was quickly seen as Mitchell’s successor as GM’s vice-president of design after the premature 1962 death of the talented Ed Glowacke. Except it didn’t happen, not then.

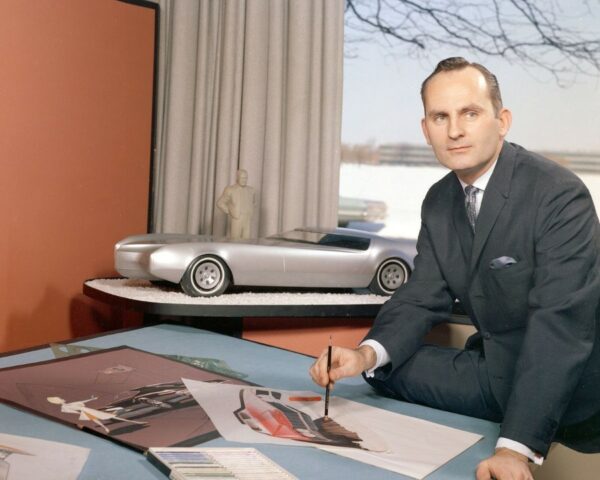

Charles Morrell ‘Chuck’ Jordan was born on October 21, 1927, in Whittier, California. His interest in cars and design began in school and he began drawing cars at age seven, won a $4000 scholarship in the Fisher (the old GM body division) Body Craftsman’s Guild in 1947, while still a student of automotive engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Until then he had always wanted to work at Ford: his first car, a 1940 Ford convertible, was replaced by a 1948 Buick convertible after he won the scholarship. Winning the annual competition meant he met, “All the GM designers, including Harley Earl, and got my first peek into a real design studio. I thought I’d died and gone to heaven.”

After graduating from MIT with a mechanical engineering degree, Jordan joined GM Design (then called Styling Staff) in 1949 as a junior engineer and designer in the truck studio where he famously developed the all-new 1955 Chevrolet pick-up. Later he was given a small, special projects studio to design an articulated, twin-engine crawler tractor, then a light-weight train for GM’s Electromotive Division. Soon after, Mitchell told him, “If you want to get anywhere around here, you have to design cars.”

Chuck knew Mitchell was right. Now in the big league, Jordan designed the 1956 Buick Centurion concept car, but he really wanted to work for Cadillac, then still somewhere close to being ‘The Standard of the World’, a style leader and an exciting place to work. Jordan told John Lamm (Collectible Automobile, June 1996) “I said to myself: Harley Earl started out with Cadillac and Bill Mitchell took over the Cadillac studio in 1936, so Cadillac looked like the place to be.”

In October 1957, Earl named 29-year-old Jordan chief designer at Cadillac. The 1958 Cadillac was just being finished and work had started on the post-seeing-the-’57- Chrysler-1959s. David Holls (later, with Michael Lamm, author of the great A Century of Automobile Styling) was the designer responsible for the high-finned 1959.

“Cadillac was the prestige studio and I wanted to be sure what we did was significant,” Jordan recalled years later. “The 1959 model was almost finished with when I took over. The studio had a 14-member team…we got comfortable with each other as we facelifted the 1960 model, so we were ready when it came time to start on the ’61.”

“The ’61 would be a clean sheet design and my first chance to do a brand-new production car,” Jordan remembered. “We all recognised it as a great opportunity, so we worked night and day. I believed in that car.”

The towering fins of 1959 were replaced by what Jordan called skegs, long pointy fins along the bottom of the rear fenders that were first seen on the 1959 Caddy Cyclone, Harley Earl’s last concept car. The skegs only disappeared on the ’63 Caddy after Mitchell told him they must go.

“We used to have photographs up on the board with all the Cadillac fronts from 1941 on, and Bill (Mitchell) felt the ’61 grille didn’t say Cadillac. It was a beautiful front, but it was like the ’39 which wasn’t a very good Cadillac either. Nothing wrong, expect it just wasn’t a Cadillac. So part of the assignment was to change that”. Instead, after he’d transferred to Chevrolet, Jordan used the original ’61 Cadillac grille on the ’63 Chevrolet. Jordan’s next major work was the spectacular 1967 Cadillac Eldorado that grew out of a series of styling exercises for a sporty 16-cylinder Caddy coupe.

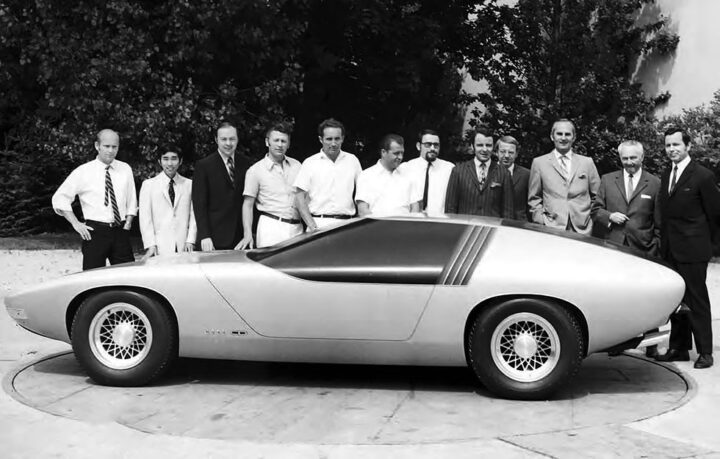

In 1967, on Mitchell’s orders, Jordan was sent to Germany as design director of GM’s Opel division. His timing was perfect, Opel was in trouble and could only go one way – up. Chuck, laughing, told me in our 1988 interview in Holden’s Fisherman’s Bend, Australia, studios, “You come in when everything is bad and go out a hero. It’s the same deal today.” In his three years at Opel, Jordan finished the GT, produced the CD show car and, from a clean sheet of paper, the Rekord 11, a smash hit, especially in coupe form.

“It was the first time I felt I had my arms around a team of designers. We worked together with vision, with a passion and, by God, we did some good stuff.”

Beautifully conceived and superbly executed, the CD and Manta shocked rival European designers. Jordan was sufficiently confident to show a Record sedan to Mitchell in front of the Board of Directors, which was taking a big risk. He got it through with little change. During his time in Germany, Ferry Porsche showed Chuck the new VW/Porsche 914, telling Jordan, “No designer touched it.” Chuck smiled and said, “It looks like it.”

Chuck always fought for design. Dave Holls remembered, “When I went to Germany, the engineers told me they wanted me to “Fight for design the way Chuck Jordan did when he was here.”

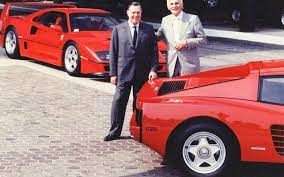

It was while at Opel that Jordan bought his first Ferrari, a Lusso. “It looks as good today as it when it came out.” Since then, the love affair flourished: Daytona, Boxer, a Testarossa, an F40, 456, 360 Modena and 348 which he quickly decided was not for him. “I still think the F40 is one of Pininfarina’s best designs – there are no ugly views. Then I found my love, the 456GT. It’s not exotic. It’s just a wonderful car. His passion extended to his model Ferrari collection, close to 4000 43:1 scale replicas.

As a Ferrari owner and fan, Jordan met Enzo Ferrari three times through their mutual friendship with designer Sergio Pininfarina. Chuck recalled once discussing design over lunch with Enzo, in the famous Cavallino Restaurant, opposite the old Ferrari entrance. Afterwards Ferrari asked Chuck if he wanted to come along on a test drive in the mountains.

Chuck remembers Enzo as an aggressive driver who deliberately did things to scare him. Still, looking back, he remembers it to be one of the best days of his life.

Later, back in Detroit, whenever Jordan became dispirited, he’d “Go out in the Testarossa for an hour and boy, when I come back, pow, it’s all together. I feel the spirit and the fire in the Ferrari. That’s a real thoroughbred car. We don’t compete with it. Not yet.”

But there was opposition and criticism of Jordan’s decision to drive a Ferrari rather than a GM product. The Wall Street Journal ran a letter to that effect in the late 1980s, the writer asking why he should put down his money for a GM car when they were apparently not good enough for the man who designed them. Valid question, though it was ignored by Chuck.

Most people at GM, including the designers, expected the enormously gifted and unassuming Ed Glowacke to follow Bill Mitchell as vice president of design when he retired in 1977. Soon after his 1958 appointment to succeed Harley Earl, Mitchell made Glowacke his assistant. They were close friends, but few knew that Glowacke was seriously ill. He died of Leukemia in 1962 aged 41. Next in line was Jordan.

In July 1977, the selection committee bypassed Jordan and named Irv Rybicki as the new design VP. Rybicki had been Mitchell’s chief assistant, with stints in all the design studios except Buick. Although Chuck Jordan was almost universally acknowledged as the better designer, Rybicki was more amiable: a team player. He was the antithesis of Mitchell and Jordan in personality, which was exactly what the selection committee wanted.

Like Mitchell, Jordan had strong design skills matched by an equally strong temper. Stylist Stan Wilen, who worked with him for years, said, “Chuck could be arrogant and sometimes downright brutal. I had to separate him once from a union shop foreman… They were actually going to duke it out.” Wilen called Jordan “a natural leader,” but his outbursts had made him many enemies within the GM hierarchy. Internally, Chuck became known as the Chrome Cobra, though never to his face.

Interestingly, when Bunkie Knudsen went from GM to Ford to become president in 1968, he attempted to recruit Chuck to join Ford as head of design. In the end Jordan stayed at GM, perhaps because Mitchell had promised Jordan that he would be Mitchell’s successor. But no one in senior management was enthusiastic about allowing his replacement to be more of the same.

Instead, GM decided that after Earl and Mitchell they didn’t have the stomach for another robust personality like the brash and aggressive Jordan and opted for “go along to get along” Rybicki, who was the textbook corporate player, avoided conflict, acceded to the wishes of others within the corporation, but arguably never truly lead anything. When accountants would demand cost cuts, Rybicki acquiesced. When Engineering and Manufacturing wanted commonality and easy-to-execute solutions no matter what they looked like, Rybicki consented. When executives decreed that a simple badge could turn a Chevrolet into a Cadillac (Cimmaron), Rybicki agreed.

Jordan responded to the news of Rybiki’s appointment with a tantrum – after coolly shaking Rybicki’s hand, he stormed out, jumped into his Ferrari and drove away in a rage. Rybicki was persuaded to make Jordan his design director. It was an uneasy arrangement. Jordan had previously been Rybicki’s boss, and he was bitter at being passed over. The two were repeatedly at cross-purposes, undermining each other’s authority and leaving their staff unsure which way to turn.

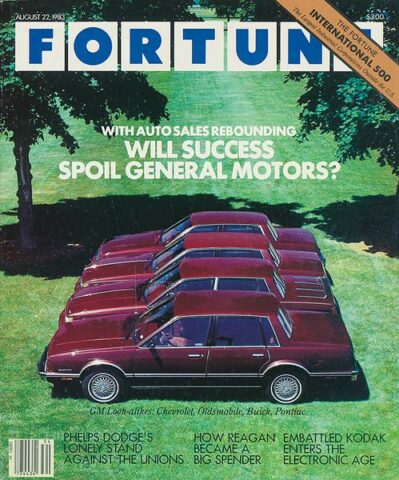

Under Rybicki the days of a larger-than-life design boss who relied on little more than his own taste to dictate the look of the company’s cars were over. GM’s styling was dominated by bland angular ‘three-box’ forms. At the same time, Government regulations safety, fuel consumption, exhaust emissions became crucial parts of the product decisions. The 1970s and 1980s were a bleak time for Detroit and GM. During Rybicki’s reign GM’s American market shared dropped from 46.4percent to 35.8percent in 1988 when the last of his designs reached the market and GM lost styling leadership. In 1983, Fortune Magazine ran a story on GM’s cookie-cutter image, complete with a famous cover photo of near identical four GM sedans, each wearing different brand badges, lined up side by side to show how difficult it was to tell them apart. The article sent shock waves through GM and forced senior management to change course.

“(The Fortune story) really yanked our tails,” said Stanley Wilen a senior GM designer. “It really got us upset; it became an infamous prod here. Not only we at design staff felt it, but then the corporation began feeling it. And all of a sudden that was one of the first objects of a program: get them different. And that was a blessing.”

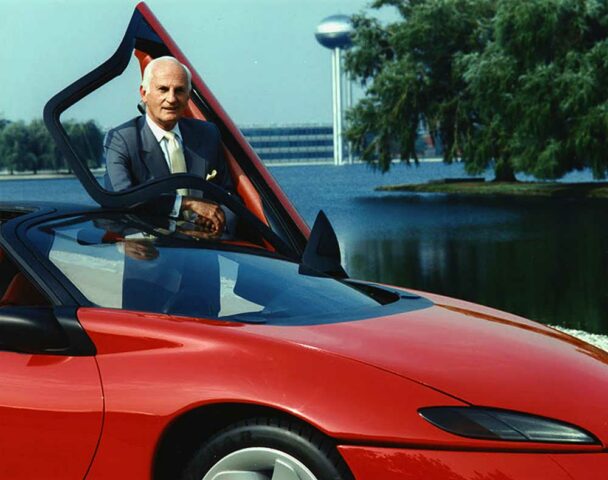

Jordan ultimately achieved the top design job in October 1986 when Rybicki retired, but only after it was too late and GM’s design leadership had been squandered. He quickly realised that he only had six years to have an impact on GM design. Chuck brought a renewed sense of energy to GM’s designs, beginning with an impressive array of show cars for 1987’s Teamwork & Technology exposition. However, the balance of power had shifted. Harley Earl and Bill Mitchell had created a unique climate of styling primacy, where engineers were obliged to follow designers’ lead as much as the reverse. By the late eighties, GM’s product decisions were no longer dominated by styling or engineering, but by accounting – the dreaded bean counters – and finance. To Jordan’s disgust, it was a victory of numbers over product.

Still, there were at least a few significant efforts to come out of the Jordan-era: the Buick Reatta, the first-generation Oldsmobile Aurora and Cadillac STS sedans, as well as the Oldsmobile Aerotech and Sting Ray III concepts. But they were too few to either create a totally positive legacy or, more importantly, stave off the steady decline in GM’s market share. The promise Chuck Jordan brought with him to the Tech Centre never materialized.

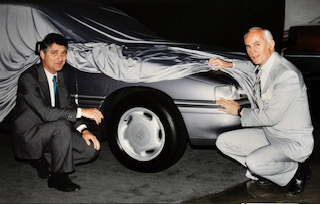

Jordan told me, “The 1992 Seville STS was one we were all proud of. When we introduced the STS, Bruno Sacco (then Mercedes-Benz design boss), whom I’d known for quite a while, said, “I never saw a car I like better than that.” That meant more to me than getting a big bonus.

It also needs be stressed that it was a time of turmoil at GM, and perhaps worst of all, Jordan, like all the senior product managers, had to report to that ultimate bean-counter, Roger Smith, GM’s Chairman and CEO. The boss patient was running the asylum.

Even so, Jordan wielded significant power, so much so that upon his November 1992 retirement, rivals made sure to clip the wings of design successor, Wayne Cherry. Respectful Cherry spent much of his own stint taking orders and watching as the hacks and bullies neutered seemingly every good design his team could come up with. The days of GM’s styling leadership were long past.

“After I retired, the culture changed,” Jordan said. “The engineers and brand managers were put in charge, with design relegated to a lower level. What happened to the Corvette is clear: the C5 was conservative. These guys were so afraid of risk, they’d say, “Oh, let’s take it to a clinic.” I mean, they took sketches to a clinic. I just about had a haemorrhage. A good designer doesn’t need Mr. and Mrs. Zilch from Kansas telling him what to do.”

Anyone who questions the potential role of design just has to look at GM history through the 1990s and 2000s. The lack of visually striking products was as critical to the maker’s eventual bankruptcy (2009) as its chaotic and confused business strategy.

When he rejoined the company in 2001, Bob Lutz tried to set it right. Just months before he arrived Lutz derided GM products as “angry appliances,” and was determined to allow the designers do what was needed again.

Cherry’s successor, Ed Welburn, wasn’t the emperor of decade’s past. Nor did he have the temperament of a Harley Earl, Bill Mitchell – or Chuck Jordan. Nonetheless Welburn relished the opportunity to make GM Design a most critical force within the company’s product development system. Offerings, like the Chevrolet Equinox, Cadillac SRX, Chevy Camaro and the Cadillac 16 concept, show what could happen as a result. However, it’s only under Australian Michael Simcoe, who took over in 2016, working closely with GM President Mark Ruess, that GM has truly returned to quality design.

Ask Jordan about great cars, the cars he called “home run cars” and he kept coming back to Ferrari. “If I came back in another life I’d like to join Pininfarina (in its golden years)”. But there are others.

“I remember the ’53 Corvette – that was a mind-blowing car. The old XK120 Jaguar was the same. The ’63 Sting Ray Corvette, boy, in its day that car with the spilt window was sensational. The ’67 Eldorado, if there is one car I’m identified with this is it.”

“There are two essential elements in the process of achieving good design: creativity and imagination. The ultimate goal is to create a design that when it hits the street, people say, “Wow!”

In the years after retirement, he took joy in teaching local high school students the art of drawing and automotive design. He was an advocate for the car design profession and its practitioners. I saw him regularly at motor shows and occasionally at major concours d’elegance like Pebble Beach and Detroit’s Eyes on Design and Meadow Brook. He was always friendly and, if I ever needed help with a story or column offered measured advice.

Chuck Jordan died on December 9, 2010 at the age of 83.

“I consider myself one of the luckiest guys alive,” Chuck once said. “All of my life I have been able to do the thing I love most – design automobiles. It’s always been exciting and fun and never quite what seemed like work.”