This is a mildly edited version of the talk AMHF board member Peter Robinson gave to the 51st National Citroen gathering in Bendigo on April 4.

Good Evening….and thank you for inviting me to the 51st National Citroen gathering.

It is far too long since I spent time in the presence of so many marvellously creative cars. Perhaps I should admit now that I’ve only owned one Citroen: a 1985 2CV Special, bought new by circumventing import restrictions.

So perhaps the best way to prove my credentials is to describe my protracted relationship with surely the most original of all automotive marques. Yet, talking to such a knowledgeable group on their favourite cars is fraught, so please forgive any errors. Your knowledge of Citroens far surpasses mine…

On Sunday, December 26, 1965, LH 254 flew me to Paris’ Orly airport. I was but 21 and in my third year as a cadet motoring journalist. My plan was simple: catch the airport bus to central Paris and find a DS taxi – only a DS – for the ride to the hotel. Ignoring the Peugeots and Renaults at the taxi rank I waited… intent on landing my first ride in a Goddess.

Unhappily, I don’t have any photographs of this adventure, so have substituted this 2015 shot.

Unhappily, I don’t have any photographs of this adventure, so have substituted this 2015 shot.

I’m not alone in thinking Citroen’s ineffable DS the most beautiful car in the world. My bias may colour any such judgement, yet I contend that the combination of absolute purity of line, originality of concept, and radical – advanced is too mild a word for the breathtaking DS – engineering and design, created a car of unsurpassed beauty.

I still stop and stare whenever I see the exquisite DS: to admire the simplicity of its shape, the flawless proportions of Flaminio Bertoni’s sculptured contours and the clarity of its detail design. Such is the depth of its cleverness, this most intellectual of all cars can still surprise 65 years after it first stunned crowds at the Paris salon in October 1955.

I lingered in the midnight cold for at least 15 minutes before a black DS taxi arrived. Wallowing in the unmatched comfort of its vast rear seat and soaking up the ride comfort of the red-fluid suspension, I knew it was the most comfortable car I’d ever experience…Who said you should never meet your heroes?

A couple of days later I hired an Ami 6, the weird, also Bertoni-styled, rebodied 2CV. I wanted the sedan with its reverse angle rear window – like a ’59 Ford Anglia – but the rental company could only offer the Ami wagon. On snow covered pre-Autoroute roads, I drove to Le Mans to lap the famed road circuit. A thrill, even with a mere 602cc, 19kW and 105km/h top speed. My contemporary notebook tells me, “duelled with a girl in pigtails, also driving an Ami”, though I doubt she was aware of our contest.

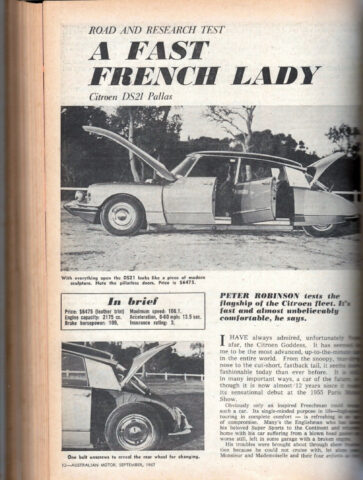

Two years later and further along in my career, I road tested a DS21 Pallas for Australian Motor Sport & Automobiles magazine, writing, “The Citroen is a long distance runner, out front and alone.”

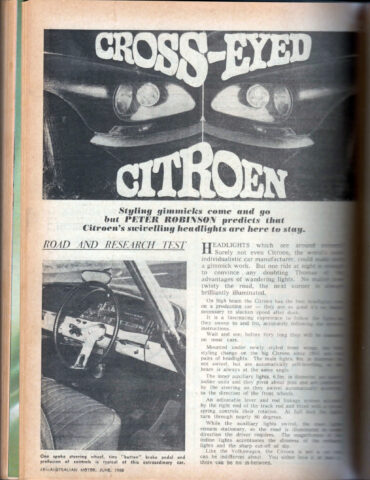

A year later, Victorian dealer John Regan lent me a new DS, the first with turning headlights.

Both came with the short-stroke 2.2-litre 109bhp engine, but the manual gearbox of the newer car slashed acceleration times: to be precise the standing quarter mile dropped from 20.0seconds to 18.9seconds and again I discovered the DS’s supreme straight line high-speed stability.

I wrote, “Citroens are not for stop-start motoring, to be really appreciated they must be driven fast on the open road – preferably one with a poor surface. In these conditions they are unsurpassed.”

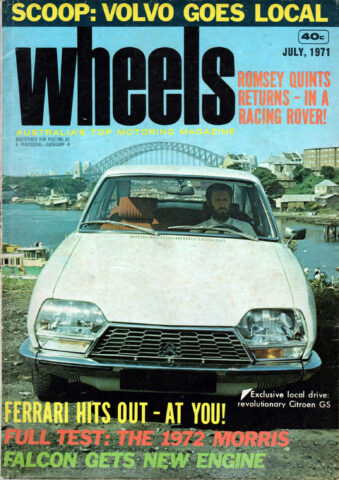

In 1971, three months into the editorship of Wheels magazine, my enthusiasm for all things Citroen pushed the new GS to the cover.

Sadly, sales of the magazine bombed….a Citroen hasn’t reappeared on the Wheels cover.

Our left hand drive test car, then the only GS in the country, came from Citco, the NSW importers, and won our admiration for all its traditional Citroen qualities. Still, we questioned the legibility of the drum speedometer and how Australians would take to a 1.0-litre car priced 50percent higher than the local Holden and Falcon sixes?

A year later, word filtered through of the arrival of Australia’s first SM, converted to right hand drive by Chapel Engineering in Melbourne.

The SM shared garage space with a Ford Thunderbird and a Buick, which perhaps explains why the owner’s wife found the manual Citroen hard to drive. Hence, LAB 888 was for sale….

After a day’s driving the ‘cloud nine’ SM, I wrote, “Revolutionary in the true sense of the word, complex, sophisticated and completely captivating, the SM represents a realm of motoring beyond the imagination.”

I wanted an SM then and I want one now.

The CX finally arrived in Australia in 1976 and, initially, came as something of a disappointment, perhaps because our expectations for any DS-successor were too high. Low gearing suggested the need for a fifth ratio, wind noise was excessive, the air conditioning weak but, most of all those early cars, with their manual steering, just didn’t feel like a traditional effortless big Citroen.

The CX finally arrived in Australia in 1976 and, initially, came as something of a disappointment, perhaps because our expectations for any DS-successor were too high. Low gearing suggested the need for a fifth ratio, wind noise was excessive, the air conditioning weak but, most of all those early cars, with their manual steering, just didn’t feel like a traditional effortless big Citroen.

Even with almost five turns lock to lock the steering was heavy at low speeds and demanded too much lock in any given driving situation. We told readers to wait for the much faster power steering, promised for a few months hence.

In mid-1982 we again tested the CX and proclaimed “Promise fulfilled”. The car came from Jim Reddiex and did everything we expected. The CX Reddiex loaned us corrected almost all of the early 2200’s flaws: its 2.3-litre injected engine came with a five-speed gearbox and variable power steering that felt like the SM, and instantly appealed. My old enthusiasm for Citroen returned. Again a big Citroen achieved the high-speed-lounge-room-on-wheels of the DS.

I called it “quite simply the most comfortable sedan in the world.”

Sadly, around that time, the Government’s complex quota system saw the number of Citroens allowed in Australia reduced from 870 in 1975 to 400 cars in 1979. New agents Brysons’ attempt to resurrect the marque failed and they gave up, selling its Citroen quota to BMW. This left Jim Reddiex’s Maxim Motors with just 102 quotas for Australia. So low were the numbers that for a time Citroen took Australia out of its manufacturing computer. There were rumours Leyland Australia, newly appointed as Peugeot distributors, might take over Citroen.

That didn’t happen and after quotas were finally eliminated in 1988, Citroen distribution passed through a number of hands, a situation that continues to this day when, sadly, only a limited range of C3 and C5 models, and not even a Berlingo, are offered.

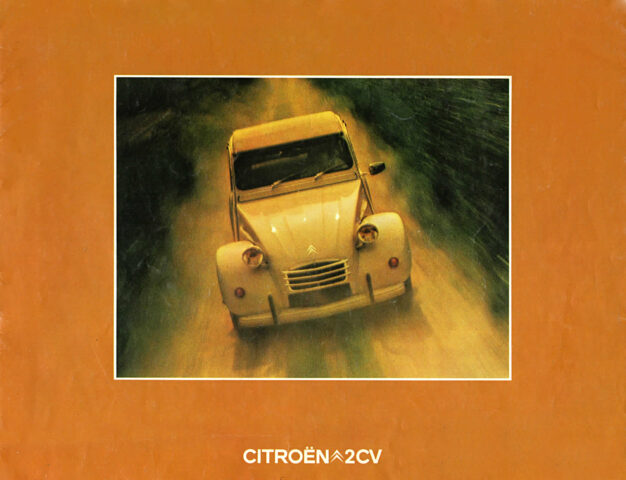

In late 1984, while staying in London with my friend Steve Cropley, then editor of UK’s Car magazine, I whinged that the stiff and notchy manual gearbox and sharp clutch of my loaner six-cylinder Jaguar XJS made driving smoothly in London’s heavy traffic difficult. Steve suggested I borrowed his 2CV and we swap cars for the weekend. I had hoped for nothing less. Not for a moment did I miss the Jaguar.

In late 1984, while staying in London with my friend Steve Cropley, then editor of UK’s Car magazine, I whinged that the stiff and notchy manual gearbox and sharp clutch of my loaner six-cylinder Jaguar XJS made driving smoothly in London’s heavy traffic difficult. Steve suggested I borrowed his 2CV and we swap cars for the weekend. I had hoped for nothing less. Not for a moment did I miss the Jaguar.

The 2CV’s charm, its ease of driving and practicality, were ideal in London, the performance entirely adequate, the ride superb. And I fell for the 2CV advertising campaign.

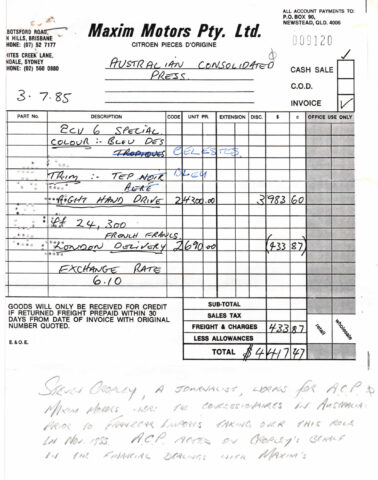

I handed back the Struggler, Steve’s nickname for his bright red 2CV Special, and immediately began to plot to buy a new example and import it home to Australia. In late 1984, I persuaded Kerry Packers’ Australian Consolidated Press, which owned Wheels magazine, to bid for the rights to produce the official program for Australia’s first World Championship Grand Prix. When Wheels won the tender, I was asked what I wanted for the extra work? Management agreed to buy me a 2CV. Time to comb through my collection of 2CV brochures.

At the time, Australia’s import laws meant that if you owned a car outside the country for three months and then brought it back it could be registered as a tourist delivery car.

That’s what I did: ACP bought the Celeste blue 2CV Special in Steve’s name, though he did not see the car until two years later when we registered the 2CV in my name in Sydney. The little duck was everything I wanted: so utilitarian that with the rear seats removed it collected bookcases and Christmas trees. The skinny 125 x 15 Michelin X tyres provided traction that bettered many four wheel drives, the engine always willing, even if progress was slow.

The lack of a radio annoyed my sons, though I doubt they’d hear anything above the throb and thrash of the air-cooled twin. Why, oh why, did I sell it? ORA 858 where are you?

By the way, have any of you seen Andrew Frankel (Autocar magazine and The Intercooler website) and Chris Harris (Top Gear) racing their 425cc 2CV across an English field? Delightful story.

Having moved to Italy to work as European editor of the UK’s Autocar magazine in 1988, I attended the May 1989 XM launch in the south of France. For the XM, Citroen management sought four design proposals: Two came from the in-house studio under Carl Olsen, one from Bertone and the fourth from Marcello Gandini, by then an independent designer who, while at Bertone, had earlier been responsible for the controversial BX. Bertone’s proposal was accepted after styling clinics played a part in ensuring the design was “correctly targeted”.

The result was no DS, but distinctive and obviously a Citroen.

Again, the new Citroen’s ride combined the ability to adjust the suspension, were overwhelmingly the car’s best feature, even taking into account the availability of a V6 version, the first six in a Citroen sedan since the Big Six went out of production in 1955. The SM, also V6, could never be given such a prosaic definition was sedan.

Later the same year I compared the XM with a BMW 530i and Rover’s Honda Legend-based Sterling. The BMW won, but the XM finished a close second.

More interesting by far was evaluating the XM with its predecessors: all drawn from the company’s vast, then secret, collection of old cars.

Citroen delivered a 1954 Big Six 15H, the six-cylinder Traction and the first car to feature hydropneumatic suspension, if only at the rear; a 1973 DS Pallas 2.3 driving through a four-speed semi-automatic gearbox; a 1972 SM, with its claimed 0.25cd drag factor; one of the last CXs, here in GTi form and firm riding to the point of being harsh; and the new XM as a V6.

Citroen delivered a 1954 Big Six 15H, the six-cylinder Traction and the first car to feature hydropneumatic suspension, if only at the rear; a 1973 DS Pallas 2.3 driving through a four-speed semi-automatic gearbox; a 1972 SM, with its claimed 0.25cd drag factor; one of the last CXs, here in GTi form and firm riding to the point of being harsh; and the new XM as a V6.

My idea was to discover how true the XM was to its historic ancestry. What we gathered was an automotive quintet of exceptional courage and far-sighted thinking. The assemblage also represented a history of the family car according to Citroen, at least until the arrival of the much-delayed C6 in 2005.

Will you be surprised to learn that we found the DS the most convincing expression of all that Citroen wanted to achieve, then came SM, the Big Six, despite its extremely heavy steering, followed by the XM, leaving the CX trailing. Yes, trailing, rather than last. The reality is, today I’d be happy to have any of them in my Theoretical Car Room. garage.

Around 25 years ago, rumours of a still secret Citroen bunker first surfaced.

Located somewhere in the suburbs of Paris, it was said to contain a stash of hundreds of historically important models, including once hush-hush prototypes. I was desperate to gain access. My enquiries were ignored, normally helpful Citroen people denied any knowledge of the collection, despite their having produced that great selection of cars in 1989.

Frustrated at not being able to breach the secrecy while living in Europe, I retired disillusioned, knowing one of the few genuine possibilities on my now short automotive bucket list remained unfulfilled.

Not quite. In early 2015 I mentioned the collection to Tyson Bowen, then Citroen’s new pressperson. A few weeks later the always helpful Tyson rang to ask if I’d like to go to Paris to see the Citroën Conservatoire. I’d retired from full time work the year before but this, I know you will understand, was impossible to resist.

Tucked off to one side of Citroen’s old Aulnay-sous-Bois plant, which closed in 2013, and close to the A1 autoroute heading north to Charles de Gaulle airport, is a low, nondescript gray and mirrored-glass building surrounded by near empty car parks. One double-chevron logo adorns the awning at the entrance of a structure that was purpose built to house nearly a century’s worth of Citroens, including several rare one-of-a-kind models and an example of nearly every model the company has produced.

Before the museum’s inauguration in 2001, most of the cars, engines, documents and memorabilia were scattered throughout northern France in various PSA Peugeot-Citroën factories. During the 1980s and 1990s, when Citroen’s creativity was minimal and it was building too many boring cars under the PSA regime, the company consciously turned its back on the quirky models from the past.

Fortunately for us, under a more enlightened management, Citroen has come through the denial-period and now takes its rich history seriously.

Almost every piece of Citroën’s collection is now located in the Conservatoire, though not everything is on display.

About 300 of the circa-400 cars in the collection are on the floor at any given time and most are in excellent running condition and used on a regular basis. The others are on loan for classic car events and publicity campaigns. The archive section is located in separate rooms that boast almost two kilometres of shelf space and can now be accessed for research and to obtain detailed information on old Citroens.

At first the Conservatoire wasn’t open to the public, only Citroen clubs from around the world and the occasional lucky journalist. That changed, though today, the exhibition is closed due to COVID. For those who have not seen the Conservatoire, please think of a visit once international travel begins again. You won’t regret it, I promise.

The collection includes the first car ever made by the eponymous Andre Citroen – a 1919 Type A – which he repurchased in 1925, knowing even then that it was worth retaining. Only from 1982 did Citroen adopt a formal policy of keeping the first or the last (or both) of any new production car, all concepts and crucial engineering prototypes.

The density of innovation is obvious everywhere and takes in a rotary-powered RE-2 Citroen helicopter, the twin-engined 2CV Sahara, rotary M35 coupe, dune-buggies and Sebastian Loeb’s WRC winning cars. Most I knew, if even vaguely, but one gold mystery car confused me. Built sometime around 2000, it was a foam mock-up based on the Xantia and lacked an engine and interior.

Ordinary in appearance, except this little known styling exercise was intended for the Detroit International Auto show as a proposal for Citroen to re-enter the American market, a plan later abandoned.

It’s possible to trace the evolution of the 2CV from the 1936 TPV – French for Very Small Car – single headlight prototype to the final Portuguese production car in July 1990, the last of 5,114,966 units. Among all the 2CVs is a special display of three dusty 2CV prototypes. During the summer of 1939 Citroen built a pilot run of 250 cars, brochures were printed and everything was ready for the 2CV to be launched at the October ’39 Paris show.

The outbreak of war forced abandonment of the unveiling and for decades it was believed all but two of the cars were destroyed to prevent their use by the Germans. Until, in 1994, workmen found an additional three TPVs walled up in the attic of a barn of a farm building at a Citroen test centre.

Deliberately hidden from the invaders and then forgotten, they were discovered by accident. Today, happily, they remain covered in grime and unrestored and that, according to Citroen, is the way they will stay.

Among the many highlights at the Conservatorie:

Andre Citroen’s first car launched in 1919 as the Type A. In 1925 Citroen bought it back and it formed the basis for the current collection. Learning from Ford, Citroen quickly became Europe’s first mass-producer of cars, building 20,000 Type As in 1920.

The Traction Avant, launched in 1934, established Citroen’s reputation for radical design and engineering, though the early cars were so troublesome they went through three evolutions before the end of the year. It took until the 1936 model, one of the first cars with its rack and pinion steering, to truly establish the model they called the Steel Greyhound.

A diverse range of Traction body styles included these now highly collectable coupe and cabriolets, engines ranged from a 1.3-litre four to a 2.8-litre six. There was also a plan to stretch up to a Citroen-engineered 3.6-litre V8. The Traction 22, displayed at the 1934 Paris salon, was killed off when Michelin took over the company in late ’34. By the time the Traction went out of production in 1957 Citroen had built 760,000 cars.

These are the 1939 TPV prototypes of the 2CV found in the roof of a barn at Citroen’s Ferté-Vidame test circuit. Stashed in 1940 by workers, they had to be lifted out of the barn roof by crane. All three cars had little corrosion and were shod with their original tyres. They used a 375cc, water-cooled, flat twin, a three-speed gearbox, could be started solely on the handle and a single headlight.

Early 2VCs – revealed at the 1948 Paris salon – used a corrugated bonnet of thinner than normal steel, to retain the required strength.

Originally the 2CV came with an air-cooled flat-twin of 375cc, with 6.5kW, capacity upper to 425cc in 1955 and a 21kW 602cc in 1968. Car with a spare on the bonnet is the twin-engine Sahara. No doubt some of you will identify this 2CV from Western Australia.

After deciding they needed a four wheel drive for Africa, Citroen developed the 2CV Sahara with two 425cc engines, one in the front and one in the rear, each with separate ignition switches. Only 694 were sold, though production lasted from 1960 to 1966. In 2012 an unrestored Sahara sold in the USA for $(A)185,000.

Coccinelle C10 is the only survivor of a range of models developed by Andre Lefebvre in 1955 and 1956, the engineering genius behind the Traction Avant, 2CV and DS. The idea was to create a lightweight, water-drop shape, powered by the 2CV’s twin. It weighed just 382kg and the doors opened like gullwing.

Project C60 was intended to fill the chasm between the 2CV and DS. Designed by Bertoni this prototype dates from 1960 and features a reverse angle rear screen, like the Ami 6, and was to be powered by 1.1- and 1.4-litre flat four engines, the bigger capacity model also getting hydropneumatic suspension. Abandoned as too expensive to build.

M35 was a coupe derived from the Ami 8, powered by single rotor Wankel engine. An experimental model, it was supplied to loyal Citroen buyers for testing. The GS Birotor did make the showroom in 1973. Launched during the fuel crisis, sales were poor and the car was withdrawn after 847 units were sold.

Work on Project L, the last design by Robert Opron (who took over as design boss when Flaminio Bertoni died in 1964) began in the late 1960s. Opron himself died in late March at 89. The design brief called for the ability to fit the SM’s Maserati V6, a tri-rotor Wankel and new flat four and six cylinder engines. Launched in 1974 as the CX with conventional fours.

Designed in 1998 by Brit Mark Lloyd, Volcanne concept was planned to be unveiled at the 1999 Frankfurt show. Instead, in July 1999, Citroen management decided to hold the car back and develop it as the B5 Project that became the first C4, launched in 2004.

Shelves around one wall of the perimeter of the Conservatorie’s hanger contain dozens of intriguing scale models, most date from post-1980s, though there are a few from much earlier. Some are obvious production cars, others pure fantasy, all deserve a good look.

It’s now common-knowledge that the DS should have been powered by a horizontally-opposed six-cylinder boxer engine – air and water cooling were tried at the prototype stage – but instead ended up with an evolution of the old four-cylinder lump from generations of Traction models. What I didn’t know until seeing the Conservatoire was that Citroen explored a variety of different engines during the DS’s near 20-year life cycle. Among many DS on display, including the oldest known example (a prototype produced in July 1955), is a hard worked 1967 mule, powered by a supercharged, two-stroke 1.8-litre V4, with the compressor driven by an independent 200cc four-stroke engine. All intended to meet California’s proposed 1975 emission standards.

It’s now common-knowledge that the DS should have been powered by a horizontally-opposed six-cylinder boxer engine – air and water cooling were tried at the prototype stage – but instead ended up with an evolution of the old four-cylinder lump from generations of Traction models. What I didn’t know until seeing the Conservatoire was that Citroen explored a variety of different engines during the DS’s near 20-year life cycle. Among many DS on display, including the oldest known example (a prototype produced in July 1955), is a hard worked 1967 mule, powered by a supercharged, two-stroke 1.8-litre V4, with the compressor driven by an independent 200cc four-stroke engine. All intended to meet California’s proposed 1975 emission standards.

Other DS engine projects included a 2.1-litre 90deg sohc V6 and a 3.0-litre 90-degree V8. The coming of electronic fuel injection and development a new range of fours of up to 2.3-litres closed the internal debate.

The thread that binds all these wonderful cars together is creativity, imagination and genius. Is it too much to hope that the creation of DS as a standalone brand allows a true revival of Citroen’s authentic character, to push the boundaries of technology and style? Given that DS is now just one of a staggering 15 brands owned by Stellantis, sadly, I suspect that might be too much to hope for.

Imagine the product planning nightmare of rationalising platforms between such disparate brands as Abarth, Alfa Romeo, Chrysler, Citroen, DS, Fiat, Fiat Professional ie commercials), Jeep, Lancia, Maserati, Mopar, Opel, Peugeot, Ram, and Vauxhall. Forgetting, too, that Stellanis is playing catchup when it comes to development of electric cars.

Finally, I thought you might like to see a custom DS, styled by ex-Holden design boss Richard Ferlazzo, the bloke responsible for the beautiful Holden Efijy. Purist may cringe, but Richard says: I am a great admirer of the DS, as any car designer would be.

Frankly, the DS doesn’t need any help, but I have often mused over the idea of a Custom DS, EFIJY style. Chopped roof, extended body and billet wheels – voila!