by Peter Robinson

Silverstone has Hamilton Straight, Scotland the Jim Clark circuit, Sydney Motor Sport Park Brabham Straight and Bahrain the Schumacher S, all named to honour the memory of famous racing drivers. And there are other corners, straights and grandstands on circuits globally called after the world’s best wheel men.

But it’s not only the drivers who star in this manner: one of the corners at the UK’s Bicester Heritage’s track is now Cropley Curve, named after motoring journalist Steve Cropley.

Cropley, for over 30-years Autocar magazine’s editor-in-chief, was one of the first journalists to see the enormous potential in Bicester Heritage, a former RAF airfield on 180 hectares that is now home to over 50 specialist automotive businesses: restorers, a motoring magazine, classic insurance companies and auction houses, plus a gin manufacturer.

In the interests of full disclosure, I should acknowledge that Steve Cropley is a mate. In fact, I’m the bloke who gave Steve his first job in motoring journalism. That was way back in February 1973, when I was editor of Australia’s Wheels magazine.

Five years later, after establishing his credentials in a highly competitive occupation, Steve defected to join Mel Nichols (another ex-Wheels staffer) at Car magazine in the UK, becoming editor in 1981 when Car was the world’s best and most influential motoring title.

In 1989 Steve and a couple of colleagues took the plunge and started their own magazine. Two years later they sold Buying Cars to Haymarket Magazines, publishers of Autocar. His weekly Autocar column followed and shortly thereafter Steve became the magazine’s editor-in-chief.

A year or so ago, Steve started working four days a week, but soon realised that was not only impractical, but unenjoyable. So he’s back to five days, still producing a prodigious output of compelling stories, his copy clean and accessible, while managing to keep abreast with the new technology of a constantly changing media.

All this, plus his ongoing efforts mentoring young journalists, is combined with an undiluted enthusiasm and enjoyment for all things car… his disparate stable currently includes an Alpine A110, Mini-Cooper S, Dacia Duster and, most recently, a Ford Ranger Raptor. This passion and commitment, so obvious in the weekly Autocar column and now in his My Week in Cars Autocar podcast (with Matt Prior), has truly made Steve Cropley one of the world’s great and most influential motoring journalists.

Now that his name is applied to the corner of a motoring racing circuit, I think it’s time for me to explain the truly extraordinary journey that took a boy from Broken Hill, a mining town in Outback Australia, to such a level of fame.

Steve grew up under the strict tutelage of his mother Claire, an English teacher. Her motivation must have worked because Steve finished ninth of 10s of thousands of pupils in English across New South Wales in the final year exams.

Despite his success in English, after former Wheels editor, the great Bill Tuckey’s, death Steve confessed. ‘Bill Tuckey is the reason I didn’t do well at school. I was too busy reading Romsey Quints (Tuckey’s alta ego) under the desk. He’s the reason I wanted to get into motoring journalism, though as a feckless kid from Broken Hill I didn’t believe his world would ever have a place for me. Bill’s writing had everything I valued: it was warm, inclusive, authoritative, and hilarious. And always stylish. In English lessons, when teachers droned on about great writing, I privately reckoned Bill Tuckey would finish any writing race 10 lengths ahead of Shakespeare’.

Yet mostly because he loved cars, Steve decided to do mechanical engineering at the Adelaide University.

During his second year, now aware that engineering was not for him, Steve and a mate took a sickie and went off to the Adelaide cricket ground. Back home in Broken Hill, Jack Cropley, Steve’s dad was watching the same test match on tv.

When a cameraman, bored with the cricket and the seagulls, zeroed in on two spectators, beers in hand, esky between them, Jack was horrified to realise one was his son.

The telephones ran hot between Adelaide and the Hill that evening. Steve explained to his anxious parents that he intended to drop out of engineering. To Claire’s chagrin, it was the end of her only son’s formal academic education.

Instead, Steve obtained a journalism cadetship at the Adelaide Advertiser, working mostly in the finance department, where he began to dream about the seemingly remote possibility of becoming a motoring writer.

But not yet.

After three years at the Advertiser, Steve, answering the call of a friend, went into partnership in a trucking company in north Queensland. Every week, Steve battled the Cairns to Cooktown and return run, covering 650km in an old truck on a treacherous gravel road while often coping with floods, washaways and bogged vehicles. The trucking venture failed and, while plotting a return to journalism, he worked in a Wolfram mine north of Cairns.

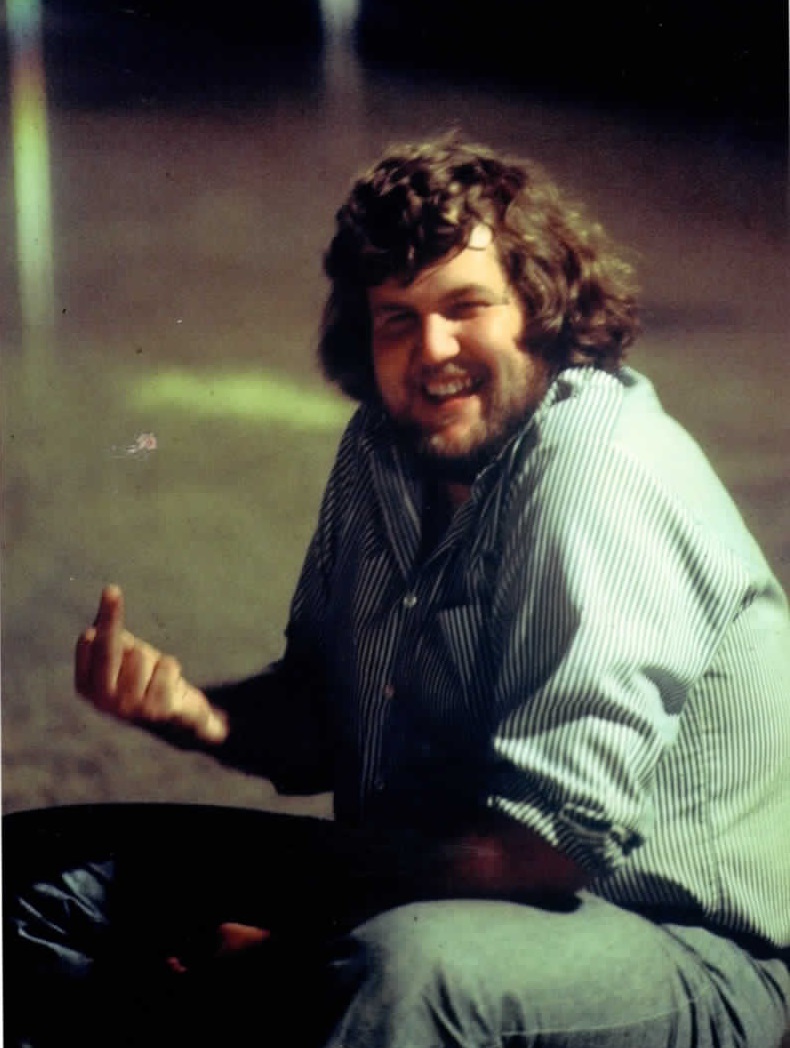

In late 1972 I advertised for an assistant editor for Wheels. Among 25 typed applications came a four-page handwritten note from Steve. He had no typewriter in Queensland. Stupidly, decades later, I gave Cropley the letter without scanning it.

However, I remember he explained his time at the Advertiser, the trucking escapade and his love of cars: he’d owned everything from a racing MG TC, early Rover 75 with the cyclops eye headlight, and Citroen Light 15, to a Hillman Minx Series 111A.

The letter was articulate, well written, it flowed and displayed a self-deprecating humour. He suggested that at six-foot two and 16 stone, he could offer a valuable insight to testing cars.

We sent Steve a telegram asking him to ring for an appointment.

Battling floods and a blown head gasket, Steve drove his aging fintail 220S Mercedes the 2400 km from Cairns to Sydney. Along the way, the girl friend who sent him a copy of my advertisement loaned him the money to buy a suit to wear to the interview.

We didn’t fill the job during the month Steve took to arrive in Sydney. Of course, the job was his… while the suit and tie permanently went into the wardrobe. When Steve married in 1989, I was the only person present who’d seen the bloke in formal attire. He swears it wasn’t the same suit.

Steve instantly became an invaluable member of Wheels’ tiny staff. I was to later learn the first car magazine he bought, aged 12, was the December 1961 issue of Wheels, still a treasured possession.

Such was his obvious talent that when Mel Nichols took off to Europe, Steve was appointed editor of Sports Car World magazine, Wheels’ sister title. Five and a half years later, in October 1978, Steve departed for the UK to work with Mel on Car. From 1981 to 1988 he became, in the judgement of Leonard Setright, Car’s best editor. Then came Buying Cars and in 1991 his move to Haymarket Magazines and Autocar where, shortly thereafter, Steve became the magazine’s editor-in-chief, a position he has held for over three decades.

Steve, one of those blessed people to have discovered his true vocation, has never wanted to be, in his words, ‘a shiny bum’ – though there were plenty of offers.

It is obvious to all that he loves being a working journalist. Ask and he’ll tell you he simply cannot imagine another career that could provide the same enduring satisfaction and pleasure. Today, at 75 Steve sees no reason to step back from the front line.

Courtesy of Haymarket Media

Nobody in motoring is more respected or has a better contact book. If Steve needs to talk to a design boss, an engineering guru, or CEO (Bill Ford, FoMoCo’s executive chairman, rang one day to complain about an Autocar story), of virtually any car maker, he just picks up his mobile.

I suspect he would be the last to admit it, but the fact is Steve Cropley knows the right people and can open doors.

Courtesy of Haymarket Media

In the late 1990s, when the UK’s Royal College of Art asked for his help in finding sponsorship for the 30th anniversary celebrations of the Transportation Design department, a single letter from Cropley to Ford president Jac Nasser produced the necessary, seven-figure funds.

Three decades ago, concerned that too many of the applicants to Haymarket’s many motoring titles lacked specialist journalistic skills, Steve begun to lobby Coventry University to start a post-graduate degree course in motoring journalism. His persistence, quiet urging and behind the scenes involvement led to the creation of just such a course in 2004.

This unique master’s degree continues today (Steve lecturing the students at least once a year) with the vast majority of the 138 graduates finding work in motoring journalism (Autocar, Evo, Top Gear, Classic Cars, Auto Express) or public relations for car companies in the UK, Europe, USA, India and Asia.

A year later, in astonishment, Steve rang to tell me he’d been asked to be the visiting professor of motoring journalism at Coventry. The one person he wanted to know was Claire, his then 92-year-old mum and, as it would turn out, in the last year of her life.

His telephone call to Broken Hill found her on a good day. Steve told her his news.

Claire understood.