by Peter Robinson

In the beginning, appropriately, it was Piero Ferrari’s idea. Enzo’s second son believed any successor to the mighty F40 should be no less than an F1 car for the road. Piero’s idea, first conceived in 1989 – only two years after the launch of the F40 and the year following the death of his father – became the prime motivation for the F50.

As the engineers struggled to turn an open wheeler into a road machine, it was Piero’s persistence and determination as vice chairman of Ferrari (with a 10 percent shareholding that makes him worth $5.5 billion) that carried his great ambition to fruition.

“In the beginning,” Piero explained to me in 1995, “it was our customers. They would come to Maranello and ask, ‘Why can’t Ferrari make something close to a Formula One car we can drive on the road.’ I tried to give an answer. Maybe, I told them, 330km/h is enough, but we could make something closer to the Formula One technology.

“People said the F40 had a fantastic engine with a lot of power, but it was still an eight. Older Ferrari clients dreamed only of a V12, the classic Ferrari engine. So, this was our first choice. Second, the F40 looked like a modern carbon fibre car, but it wasn’t true. The chassis was a tubular frame with carbon fibre parts. Our second idea was to develop a real carbon fibre chassis like a Formula One car. To combine the two was the beginning of the idea for the F50.”

Piero realised the F40’s successor should, therefore, incorporate as much contemporary motor racing technology as possible and in early 1990 his basic format for the car began to progress into hardware.

“I was thinking to use the exact layout of the Formula One of those days, when Nigel Mansell and Prost were driving for Ferrari: a carbon fibre chassis, V12 engine and six-speed gearbox. We started to design the car at the beginning of 1990.

“We decided to develop the (then) current 1990 3.5-litre F1 engine from the 641. It was very compact, very short, where our other V12s, like the new engine for the (front engine) 456, would be very difficult to fit in the rear without making the wheelbase too long. We didn’t want a big car with a big engine, our desire was to have a compact engine and a low centre of gravity.

“The challenge was to take the 3.5 litre engine and increase the stroke to make the maximum possible capacity inside the block.”

“The important thing,” Piero said, “was to keep the (exterior) dimensions of that engine, to keep it small so that it would fit in the rear. What is common to both is the 65-degree angle, the length of the block and the five valves per cylinder design for the heads: everything else has changed.”

The 641’s V12 revved to 13,500rpm and, like all F1 engines from the top teams, needed to be stripped and rebuilt after every race. Ferrari knew that for a road car, even one as specialised as the F50, that was absurd.

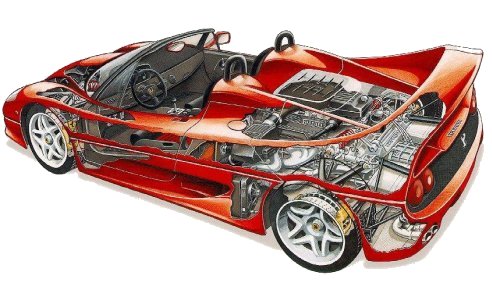

Massively oversquare – bore 85mm, stroke 69mm – the Tipo F130B V12 displaced 4698cc, with three intake valves and two exhaust valves per cylinder, the four overhead camshafts driven by two Morse chains with titanium conrods and forged aluminium pistons to permit sustained high revs. Electronics and injection were provided by Bosch’s M2.7 brain. Dry sump lubrication, of course. Peak torque arrived at 6500rpm, though Amedeo Felisa, then head of product development at Ferrari, reckoned it would be more accurate to say that the 470Nm spanned 5000-7000rpm. The redline and cutout were set at 9000rpm, the engine delivering 382kW at 8500rpm (a Ferrari naturally aspirated record of 111bhp per litre). To nobody’s surprise, in bench testing the V12 proved capable of running at 10,000rpm.

Ferrari mounted the ultra-close ratio gearbox behind the engine but, despite the engineers’ best efforts, the F1 car’s push-button automated gear change couldn’t be made to work in time and only arrived on the F355 in 1997. Close ratios: how’s 103km/h in first at 9000rpm, 138 in second, 152 in third, 180km/h in fourth and 272km/h in fifth… at the claimed 325km/h top speed the V12 was pulling 8800rpm, just 300rpm beyond maximum power, in sixth. The factory claimed 3.7secs to 100km/h, 0.4sec quicker than the F40, though the older car beat the F50 over a standing kilometre: 21.7secs to 20.9sec. Despite this the F50 was four seconds a lap quicker around Fiorano. And, of course, the McLaren F1 was quicker than both at 3.2secs and 19.6secs. (More on the F50’s acceleration later.)

Aerodynamics and the desire to develop a body that shaped itself around the mechanicals, in what Pininfarina described as a single sweep, inspired designer Pietro Camardella to create a wildly exotic form that included a dominant rear wing and somewhat bulbous nose treatment. Still, there was no denying its presence. Both the chassis, a fully load-bearing structure, and the body were carbon fibre. The F50’s monocoque, which included the 105-litre rubber-lined fuel tank, weighed just 102kg, the entire car hit 1230kg (unladen) with a 42:58 percent weight distribution. The attachment points for the double wishbone front (and rear) suspension and the engine/gearbox/rear suspension were provided by light alloy inserts bonded to the chassis, a first for a road car. And therein lay the F50’s greatest engineering hurdle.

For months Ferrari struggled to solve the question of mounting the engine directly to the carbon fibre bulkhead. There was talk of broken bulbs as the engine hit its natural frequency, filling the cabin with a level of noise and vibration that was unacceptable. Tellingly, at the drive launch Ferrari refused to allow any journalists to drive the car with the standard removeable coupe roof in place. Yes, I did ask and more than once.

“The big challenge for the F50 was the NVH (noise, vibration, harshness),” Felisa admitted. “There is no solution if you think of it as a normal car. But if this is a special car, then we have been successful, and you know it’s a Formula One car for the road. The noise is not a negative aspect of the F50.”

“I was concerned about noise problems,” Piero confessed. “Now it is still the question mark about the car.”

Ironically, given Ferrari built the F50 as an F1 car for the road, at the official launch journalists were denied the opportunity to drive the car anywhere but at Fiorano, Ferrari’s legendary test track, and in open form. Making a definitive judgement on ride quality, noise and vibrations levels or heat soak impossible. Road time, I was assured would come later…except it never did for me. The cynical might suggest that Ferrari well knew that if the F50 was going to shine it was right here on home territory as an open car without the demountable roof in place.

So it proved. For the press launch and with just two cars on hand, Ferrari invited small groups of journalists to Maranello on a day-by day basis. During the morning I shared the red F50s with two German journalists. However, the only plane from Bologna to Stuttgart left early afternoon with my friends from Auto Motor und Sport and Sport Auto on board. Leaving me with a new definition of paradise: alone for two hours in an F50 on Fiorano.

Of all Ferrari’s supercars – 288 GTO, F40, F50, Enzo, LaFerrari – the F50 is commonly considered the least compelling.

Yet, in simple terms, the F50 was the easiest of all (though I’ve not sampled the 288 GTO) to drive on the limit, balancing the car’s attitude on the accelerator, loading up the outside rear wheel, instantly detecting any loss of tyre grip. I was immediately aware that any dramatic lifting off would immediately alter the drift angle, not enough to demand premeditated opposite lock, more a tiny, imperceptible reduction in steering input.

Amid all the howls, the wails and bellows and whoops from the engine and gearbox, the F50 was benign, friendly even, and not at all intimidating. Within two laps of Fiorano I realised that although there’s taste enough of Formula One in the noise, the power, the handling, the overwhelming tactility of each element of the F50, the balance and poise of the chassis, meant everyone who drives this can feel like a hero. I could barrel out of the famous hairpin, scene of a thousand power oversteer photographs, F50 sideways and accelerating, the initial understeer, exaggerated by the need to dial in a quarter turn of lock at low speeds, had abruptly vanished, replaced by agility that came mostly via the throttle.

If I, with my driving limitations, could tighten the line at will, placing the F50 to the nearest millimetre in avoiding the ripple strips, and not ever be fearful of an abrupt snap into oversteer, then it was obvious Dario Benuzzi, Ferrari legendary chief test driver, had done his job incredibly well. The terrific thing is such safe handling was totally unexpected from so responsive a chassis and so exciting a car. For all that, I should admit to spinning, but once only, and not for the camera.

Which perhaps makes it all the more surprising that Ferrari should announce to the press that, “No, there is no press car.”

Despite this declaration, the American magazine Car & Driver was determined to obtain F50 performance figures, mostly to see if it matched the F40. America was allocated 55 F50s, all available only on a two-year lease. As well, any potential lessee, was sent a questionnaire by Ferrari. C&D quoted one interested customer being asked ‘What Ferraris do you currently own? How many Ferraris have you sold in your lifetime and for how much? Have you raced any Ferraris?’ and ‘Do you plan to race the F50?’ And so on.

In trying to find a car, Car & Driver spoken to 11 Ferrari F50 lessees over 13-months. Most expressed annoyance at Ferrari North America’s questionnaire and leasing scheme. “I always pay cash for my Ferraris,” said one. “This time, I couldn’t do that, so the car doesn’t feel like it’s mine. Throughout all of this, I’ve felt as though Ferrari was questioning my motives—me, a guy who buys another of its cars every single year.”

None of the 11 were prepared to lend C&D a car for performance testing, even if they drove the car. One explained, “I buy every new Ferrari that comes out. It was suggested that if my F50 got tested, I might not be on the list of preferred customers.”

“There are perks for being a loyal Ferrari customer,” another to the magazine. “Things like personal factory tours in Maranello and private drives at Fiorano. Maybe I have a big ego, but those things mean a lot to me. So, to be told I might lose those perks, well, you know. . .”

Finally, the magazine found a Ferrari enthusiast, who was not a lessee and had bought a European model and was prepared to let the magazine run figures on the 7.5-mile Transportation Research Center’s oval. The results were published in C&D’s January 1997 issue: Top speed: 194mph, 0-60mph in 3.8secs, and a 12.1sec standing quarter mile, essentially matching the F40.

In Japan, Car Graphic magazine – which also road tested the McLaren F1 – were loaned an F50 by another owner. running the car on the 5.5km oval track at the Yatabe (now JARI) proving ground. This F50 clocked 4.2secs to 100km/h, 11.9 over the 400metres, numbers which compare favourably to the F40 the magazine tested: 4.7secs to 100km/h, 12.2secs for the 400metres. Car magazine was forced go to the Middle East to drive an F50 on the road. However, the magazine didn’t bother with acceleration testing.

When production ceased in July 1997, Ferrari had built 349 F50s, rather less than the 1315 F40s, which probably accounts for the later car now being more valuable than the F40.

Perhaps it lacks the charisma of the F40 and the outright pace of the Enzo and LaFerrari but, if I could learn to ignore the appearance, the F50 would be my choice. Especially if I owned a suitable race circuit.