by Peter Robinson

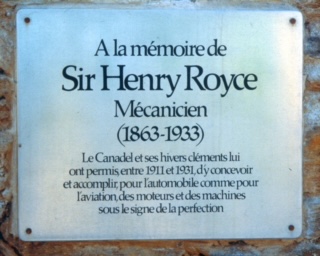

Observant motorists driving east along the Avenue de la Corniche, as it winds above the Mediterranean between Le Lavandou and St Tropez in the south of France, will notice a small stone plaque beside the road on the way into the village of Le Canadel. Those with eagle eyes will decipher the words Sir Henry Royce Mecanicien.

In 1991, Citroen’s test route for the new ZX took journalists passed the weather-beaten plaque. It was too good an opportunity to miss: I had to stop and learn more. Despite scant French, I translated the memorial to discover that this was where the great man lived for 20-years from 1911 to 1931.

I drove up the small street alongside the house and found a local. Yes, she told me, Sir Henry Royce had loved here and his house, further up the hill was now for sale. A few hundred metres beyond was an impressive gateway with yet another plaque built into a stone wall. This inscription, far newer than the one of the mainroad, said (correctly) Sir Henry Royce lived from 1863 until 1933, and celebrate his accomplishments in the fields of aviation and motoring. It suggested his name had become a symbol of perfection.

And, yes, the house was for sale according to an estate agent’s sign. A few phone calls later and, yes, the present owner, Jacques Gueudet, would be happy to show me through the place later that afternoon. I was hooked.

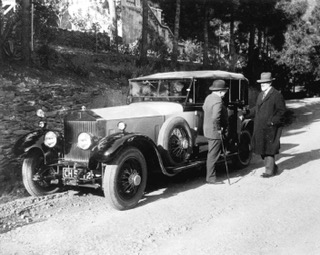

Shortly before 5.00pm Jacques arrived in his ancient Ford Fiesta and we drove through the electronically controlled gates and up the stone driveway towards the lovely ochre-yellow house. Jacques Gueudet is an enthusiastic Frenchman and the story he told was rich in automotive mythology.

According to Jacques, Henry Royce fell ill in 1910 and his doctors recommended that he spend some time in the warmer climate of the South of France. Claude Johnson, often referred to as the hyphen in Rolls-Royce (indeed there’s a book of that name by Wilton J. Oldham which tells the story of Johnson’s life), found an hotel near Canadel. Henry was so taken with the area that he instructed Johnson (CJ, as he is known to Rolls-Royce enthusiasts) to buy some land and build four houses. One was for Royce, another for Johnson, the third was to be a place for Royce to work and the fourth would accommodate house staff.

Gueudet told me this was soon accomplished, and that Royce then spent his winters living in France with his nurse, before he returned to England, where he died in 1933.

Apparently, the house was owned by the Rolls-Royce company, which sold it in 1933 to M. Mestre, who made his money from a chain of French car accessory supermarkets, and then lived in Monte Carlo. From around 1965 the house – Jacques referred to it as Villa Jaune – was left vacant. However, in 1981 Rolls-Royce expressed an interest in buying the house back and, in partnership with a Belgian firm, turning it into an exclusive hotel. When the socialists came to power in France the deal fell through.

Seven years later, Jacques was offered the house and, knowing of its history, approached various banks who loaned him the money to buy the two-acre property. Jacques claimed that it was only on the strength of the Rolls-Royce reputation that he was able to borrow the money. He built (and then sold) six small houses on the land to help pay back the banks, plus two additional guest bedrooms below the main part of the house. The restoration was completed in October 1990 and now the Villa Jaune was for sale at a cool 1.6m pounds ($4m in 1990).

Jacques produced an elaborate glossy brochure to help sell the villa. It claimed, “Sir Henry Royce lived in this house at Canadel from 1911 to 1931.” Jacques used as his reference, in claiming Villa Jaune was Royce’s home, a book called The Rolls-Royce Motorcar and Bentley by Anthony Bird and Ian Hallows, now long since out of print.

However, The Rolls-Royce Heritage Trust’s book Henry Royce – Mechanic tells a subtly different version that suggest the villa for sale is actually Claude Johnson’s home and not Royce’s, which was called Villa Mimosa and is located just down the hill.

This book explains, “CJ already had a hillside villa at Le Canadel and R (Royce) was so enchanted with the view from it down to the sea that he decided he could quite happily work there. CJ seized the opportunity and acquired land to establish quite a colony. Below CJ’s Villa Jaune there were to be R’s villa Mimosa, Le Bureau for the design office and Le Rossignol to house the designers. Whatever the original intention, the main one was that R should spend the summer in the south of England, within reach of the works, and the winter at Le Canadel.”

Photographs in the book, taken shortly after the four houses were built, substantiate the fact that the building highest up the hill is in fact CJ’s home.

The late Lieutenant-Colonel Eric Barrass, then historian of the Rolls-Royce Memorial Foundation, confirmed the view that Villa Mimosa is the Royce home. Anthony Bird died many years earlier, but his co-author Ian Hallows told me them they had drawn upon a book, The Life of Sir Henry Royce, written by Sir Max Pemberton and published a few years after Royce died in 1933, as the source of information on the years at Canadel. However, the book is a little ambiguous in its detail on the colony at Canadel, although it does suggest Mimosa was Royce’s home.

In Barrass’s view, Henry Royce was “more than a workaholic” and it was over-work that led to a complete breakdown in his health in 1910. Specialists gave him three months to live. Claude Johnson refused to accept the prognosis so a nurse, Ethel Aubin, was hired to look after Royce. At the time Royce’s marriage was already shaky, and his wife Minnie and adopted daughter, Minnie’s niece Violet, resented the control exercised by Aubin. After the houses in Le Canadel were completed in 1912, patient and nurse would leave England in October and return in the spring.

Shortly after they moved to Canadel, Royce suffered a recurrence of cancer of the bowel and had to be rushed back to England in a Rolls-Royce converted into an ambulance. This led to have his what Barrass says was the first colostomy operation in the UK. Nurse Aubin was now completely in charge of her patient and the Royces separated, although they were never divorced. Henry ensured they were provided for until Minnie’s death. Violet died in 1987.

It was CJ’s idea to keep Henry away from the works – Barrass says he never returned to the Derby factory after 1912 – so a great deal of his design and engineering work was carried out at Canadel. The World War I Eagle and Falcon aero engines were deigned there, as was the Phantom I engine and (probably) the Phantom III V12. Here, too, work was carried out on the ‘R’ engine that won the Schneider Trophy in 1929 and 1931 and the V12 engine that was later to be called Merlin and powered the Spitfire.

While Royce was spared the day-to-day problems of running the company, managing director Claude Johnson was forced to accept an increasing workload as the company expanded. Ignoring his own advice to Royce, CJ died at the age of 62 in April 1926. In 1930 Henry Royce, mechanic, became Sir Henry Royce, baronet, OBE, MIME and MIEA. Not that it stopped him working until his death three years later.

Villa Jaune and Villa Mimosa are an integral part of the history of Rolls-Royce and, if you have the money, can be enjoyed today.

In 1991 the Villa Jaune – five bedrooms, five bathrooms, two living rooms and a dining room – was for sale. Today, you can rent the villa for an astonishing $(A)4123 per night. Villa Mimosa is currently also available for rent at a mere $2400-$7400 per week, depending upon the season.

For Rolls-Royce enthusiasts the temptation must be irresistible.