by Peter Robinson

This is a coincidence that stretches beyond the imagination. In late 1950 and early 1952, General Motors and Ford – sworn rivals as the world’s two biggest car makers – launched totally new four- and six-cylinder engines with identical bore and stroke measurements and, therefore, precisely the same capacity. A fluke of engineering or something entirely different?

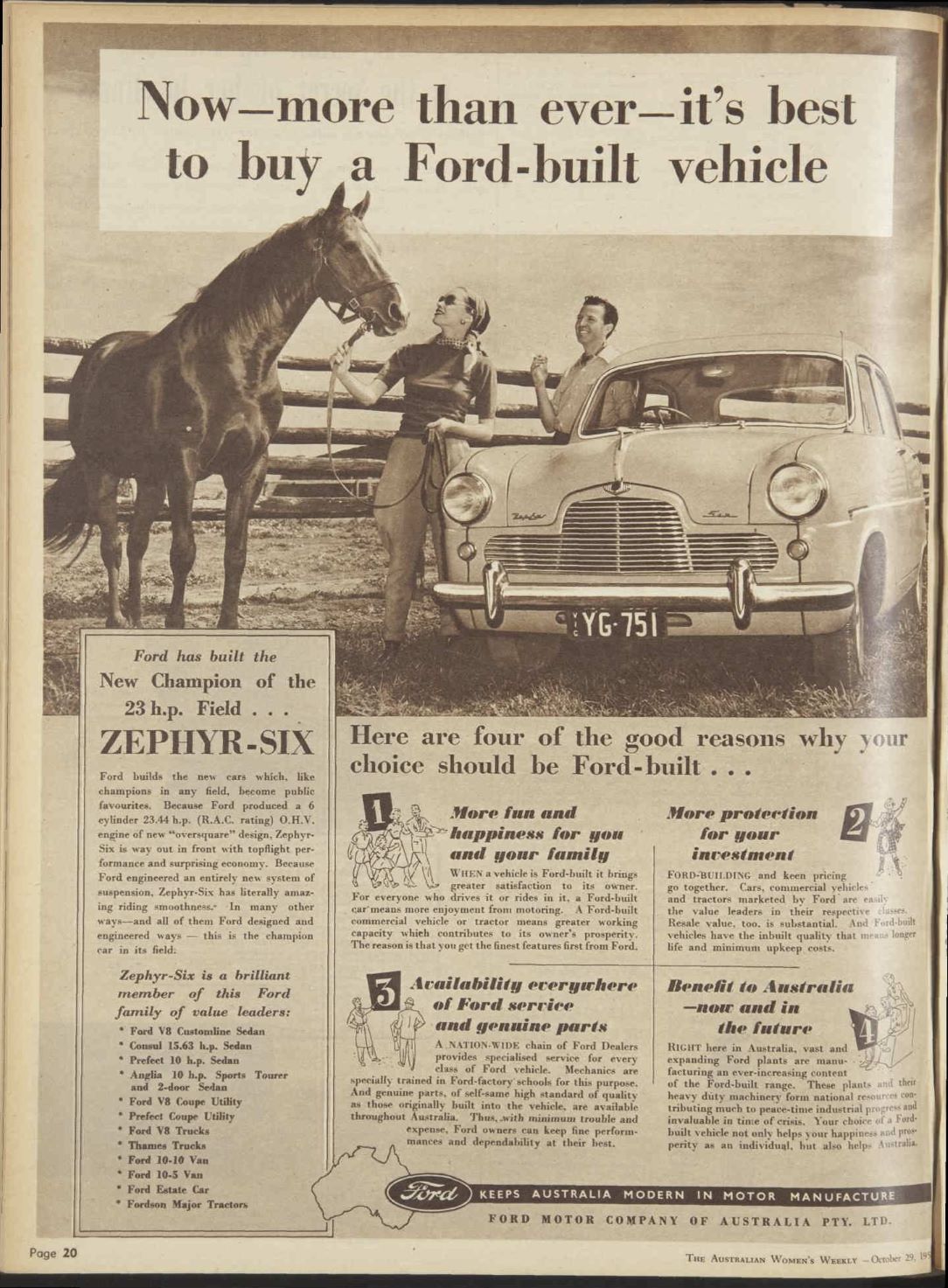

Ford unveiled its revolutionary new Consul and Zephyr models at the October, 1950 London Motor Show. The new, short-stroke overhead valve engines featured 79.37mm (3.12inch) bore and 76.2mm (3.00inch) stroke, the four-cylinder Consul giving 1508cc (91.7cid) and the six-cylinder Zephyr 2262cc (137.6cid). The Consul went on sale in January 1951 with the Zephyr following just a month later.

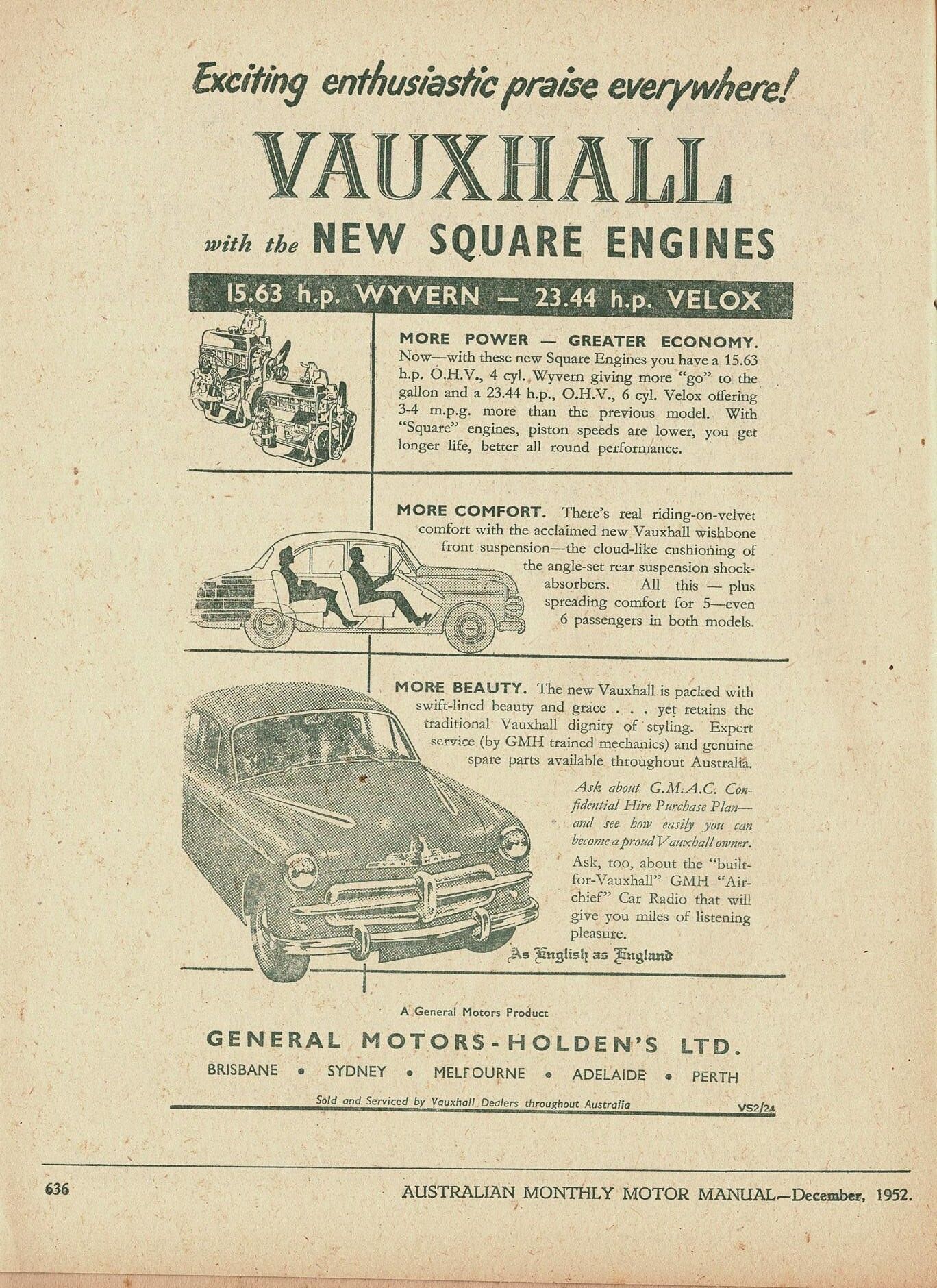

In April 1952, Vauxhall finally replaced the ancient long-stroke engines of the just six-months’ old Wyvern and Velox models with new short-stroke ohv four and six-cylinder engines of identical – yes, to the nearest cubic centimetre and millimetre – dimensions.

Until re-reading a comparison between the Zephyr and the Vauxhall Cresta (the luxury version of the Velox) in the July 1990 Classic and Sportscar magazine, I was unaware of the duplicated engine dimensions. At first glance, I thought the matching engine specifications in the data panel was a sub-editing error. A quick check confirmed their matching bore and stroke and engine capacity. How was this possible, I wondered?

The following C&SC issue contained a letter from respected English motoring writer John Simister asking the same question. After pointing out the obvious parallels, John wrote, “Was it the attraction of a simple 3.00inch stroke that drove ostensibly independent teams of engineers to identical sizes for these first oversquare mass-produced engines from British manufacturers? Does anyone out there know the truth?”

I anticipated learning more as I opened the following issue (yes, I have an almost complete set of the magazine from the first April 1982 issue).

Philip Turner, a respected staff journalist (1953-1988) on The Motor magazine, replied (Classic and Sportscar, September 1990), “When I asked the same question once while having lunch with the Vauxhall people, I was told that both the Zephyr and the Cresta power units had a common ancestor, namely a post-war project for a small Buick.

“When it was decided not to proceed with the project, the design staff immediately responsible for it migrated to Ford in Detroit where they were responsible for the general mechanical layout but more especially the power units of the Consul/Zephyr. However, GM later hauled the shelved small Buick designs out and used them first for an early Holden and then for the basic layout of the E-type Wyvern, Velox and Cresta.

“This background would seem to make more sense than such a very long arm of

coincidence.”

By then I was utterly enthralled by the mystery of the matching GM and Ford engines, although I knew that Turner/Vauxhall were wrong about the origins of Holden’s original grey motor. This engine dated back to GM’s pre-war 195-Y-15 small car prototype and was a long-stroke design – 76.2mm/3.00ins bore x 79.4mm/3.125in stroke for a 2171cc/132.5cid capacity.

However, Turner’s response provided an all-important clue. I suspected that rather than a small Buick (which nobody at GM’s Heritage Center in Detroit is aware of), the Vauxhall executives were referring to the Chevrolet Cadet, the innovative small car project run by GM’s brilliant engineer Earle MacPherson.

Now for the history lesson that is vital to my theory.

On May 15, 1945, GM announced plans to build “a lighter weight and more economical car in the post-war period”. The proposed Cadet, Chevrolet’s baby, never made it to the showroom but that didn’t stop it from becoming one of the most influential cars of all time.

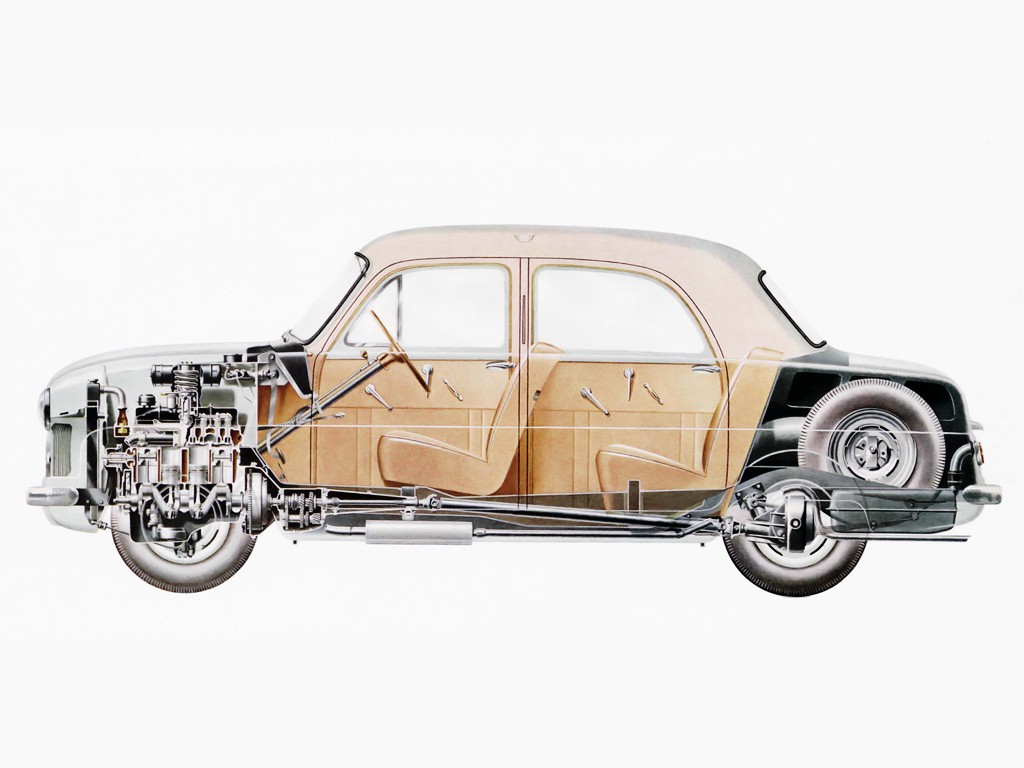

MacPherson’s inspired creation aimed for a target weight of 2000lb (907kg) for the four-seater. The Cadet was to be built on a 108inch (2743mm) wheelbase, eight inches shorter than the regular Chevrolet. But it was the suspension that was truly revolutionary. What MacPherson did was to combine tubular shock absorbers with external coil springs in tall towers that also served to direct the vertical travel of the wheels and, at the front, acted as the pivot line around which the front wheels turned. At a time when leaf springs and solid axle front suspension were still prominent, the idea was radical indeed. MacPherson wanted his suspension at both ends of the car to give the Cadet four wheel independent suspension and, therefore, reduced unsprung weight to make for a good ride and to give more rear seat and boot room. To reduce weight further, it was also to get tiny 12-inch wheels.

Other conventional engineering principles were ignored. The Cadet was to have a fully integral monocoque body when almost every other American car (Nash in 1941 was the first exception) rode on a separate chassis; its brake and clutch pedals were suspended from above – rather than coming through the floor – to work hydraulic cylinders via linkages. His 2.2-litre overhead valve six looked conventional but was slightly oversquare – bore 77.8mm/3.0625in x 76.2mm/3.00inch – for a capacity of 2173cc/132.6cid. At the time 7.25:1 was a high compression and helped the engine to produce 64.5bhp/48kW at 4000rpm. Unusually, it had a flywheel at both ends of the crankshaft and this allowed the rear flywheel to be just big enough to suit the clutch.

Early tests showed the suspension struts needed modifications to improve durability and eliminate squeaks. Even so, the first Cadets showed outstanding handling and a better ride quality than even a contemporary Cadillac, which did not go down well in parts of GM. The major deficiency was the poor performance of the brakes.

However, there was another more significant weakness. The Cadet was not going to be cheap to produce and would certainly have cost far more than the projected $1000. To reduce costs the team designed both Hotchkiss and torque-tube rear suspension, though they fought hard to prove how much better the car would be with the independent suspension.

A shortage of basic materials also counted against the Cadet: many argued that any available materials should be used for GM’s bigger, more profitable cars. In early 1947 GM’s all-powerful financial staff calculated that Chevrolet would have to sell 300,000 Cadets a year to earn an adequate profit. Chevrolet sales department said the target was too high. MacPherson would not give up and devised a cheaper single-leaf spring rear suspension, but it was not enough. On May 15, 1947 GM announced, “The proposed Chevrolet lighter car project has been indefinitely deferred due to a continuing material shortage.”

Devastated by events, MacPherson was only too willing to move camps when he was approached by Ford’s Harold Youngren. In September 1947, aged 56, MacPherson left GM and joined Ford in Dearborn.

Little more than three years later the British Consul and Zephyr appeared. Developed in Dearborn by a team led by MacPherson, they had slightly oversquare ohv engines, monocoque bodies, pendant pedals and, crucially, the MacPherson strut front suspension. It is one of the lovely ironies of motoring history that MacPherson’s GM Cadet was ultimately built by Ford. (Tragically, the last surviving Light Car Project Cadet prototype was scrapped by GM in 1968).

The engineering lessons of Cadet may have been largely ignored within GM, but I reckon the Vauxhall executives who spoke to Turner were right: MacPherson took the Cadet engine and adapted it for use in the new British Ford models (with the benefit of hindsight, perhaps the most innovative British Fords ever). Around a year later GM, realising Vauxhall’s desperate need for modern engines, revived the proposed Cadet engine for the Wyvern and Velox.

Not that the Ford and Vauxhall engines were otherwise identical.

A month later (C&SC November, 1990) reader Michael Allen, who I suspect may have worked for Ford, replied, “Apart from these particular (capacity and bore and stroke) similarities, the two blocks differ completely. The Vauxhall engine, which appeared 17-months after the Zephyr unit, is in fact a far less rigid affair than that of the Ford, as the latter is of the deep skirt type, giving much greater rigidity and altogether better support for the crankshaft, whereas the Vauxhall block terminates at the crankshaft centreline. Vauxhall had, in fact slipped up badly from the long-term point of view, for although it performed well and very reliably in the E-model Velox, the block was incapable of further development.

“For the considerably more powerful PA series Velox which came in 1957, a completely new block, this time deep skirted, was designed around the same bore centres and allowed the same stroke – a rather expensive exercise for an engine of identical capacity and the same bore/stroke ratio as before. Even this stronger unit only sufficed for three years’ production, as, when a larger capacity was deemed necessary in 1960, yet another block, longer by 21/4in and with wider bore spacings, was needed for the wider diameter bores.

“In sharp contrast, the basic Ford design sufficed for three distinct generations of Zephyr, having been schemed out in the beginning with larger main-bearing areas and an allowance for increased bore diameters at a later date without sacrificing the generous water jacketing encircling each cylinder.

“The Ford Mk 1 cars were designed in America, but with the assistance of Dagenham engineer George Halford who spent 18-months at Dearborn as a member of the design team. Neither of the two American Ford engine draughtsmen working on the Mk 1 had come from General Motors.

“But there was one ex-GM man at Ford involved with the Mk 1 project. This was Earle MacPherson who had brought with him his brilliant independent front suspension design which the Consult and Zephyr were to introduce to the motoring public.”

I put my theory, and Allen’s response, to David Booker, who runs the amazingly complete [email protected] website devoted to all things Vauxhall and includes a marvellous selection of secret design proposals.

“Interesting thought, but I think it was actually a coincidence. I confess that I am no expert on Ford engines, however, the Vauxhall 2262cc “square” engine and the smaller 4-cylinder version were developed under Maurice Platt [Vauxhall Chief Engineer, PR] as a direct response to the change in Britain’s archaic taxation system that had given rise to long stroke, low revving engines and the almost uniquely British “pint-size six”. Vauxhall was not alone, and the industry as a whole was moving in the same direction. Ford was well known for its “espionage” activities within the industry and it is possible they found out what Vauxhall was doing, but I can’t see any reason other than the general principle of a “square” bore and stroke (as to) why they would choose to copy the dimensions exactly. The actual design of the engine was very different to the Ford and had a far greater stretch built-in [largely for Bedford use] as essentially the same unit ended up being enlarged to 3294cc for the last of the PB models. Many have claimed it was a Chevrolet engine, which it wasn’t, but it did share many engineering features with Chevrolet engines at the time but nothing I know of Buick apart from generic GM engineering practices.

Later he followed up with this:

“I think Michael Allen was getting swallowed up in Vauxhall period publicity hype, the PA engine was introduced in the last of the E-Series models and was no more than a development of the original engine with a modified and strengthened [not completely new] block, larger valves and individual vs siamese porting. Developments such as these continued through the life of the engine, including six modifications to the cylinder heads. If Vauxhall were going to design a “completely” new engine as suggested then they would have, as a matter of course, added a 7-bearing crankshaft which was the engine’s biggest shortcoming and the cause of the renowned crank “waggle” in the larger capacities. Therefore I stand by my original observations.”

Maurice Platt’s 1980 book An Addiction to Automobiles mentions the new Ford ohv engine but, strangely, if he was involved in its creation, does not reference Vauxhall’s similar engines. Platt’s ignoring what was a fundamental shift to ohv short-stroke engines leads me to believe the Vauxhall engine design basically was resurrected from the Cadet via MacPherson from the GM in Detroit. My theory that both engines evolved from MacPherson Cadet holds up. Seventy years later, as Simister asks, does anyone out there know the truth?”

Astonishingly the coincidences don’t stop with the British Fords and Vauxhalls: for Holden’s 1960 FB the grey engine’s bore was increased to 77.88mm/3.063ins to give a capacity of, guess what? 2262cc/137.6ci.

| Make/model | Ford Zephyr | Vauxhall Velox | Holden | Chevrolet Cadet |

| Model identity | EOTTA | EIPV | 48-215 | Light Car |

| Launched/On sale | London Show (Oct 1950) (onsale Feb 1951) | April 1952 | November 1948 | 1945-47 |

| Engine | OHV in-line six | OHV in-line six | OHV in-line six | OHV in-line six |

| Capacity | 2266cc/137.6cid | 2266cc/137.6cid | 2266cc/137.6cid | 2266cc/137.6cid |

| Bore | 79.37mm/3.125in | 79.37mm/3.125in | 76.2mm/3.0in | 77.8mm/3.0625i n |

| Stroke | 76.2mm/3.00in | 76.2mm/3.00in | 79.4mm/3.125in | 76.2mm/3.00in |

| Compression | 6.8:1 | 7.5:1 | 6.5:1 | 7.25:1 |

| Power | 68bhp/51kW @ 4000rpm | 65.5bhp/48kW @ 4000rpm | 60bhp/45kW @ 3800rpm | 64bhp/48kW @ 4000rpm |

| Torque | 112lbft/152Nm @ 2000rpm | 108lbft/146Nm @ 1200rpm | 100lbft/136Nm 2000rpm | 108lbft/146Nm @ 1200rpm |

| Weight | 2660lb/1207kg | 2475lb/1123kg | 2247lb/1019kg | 2200lb/998kg |

| Wheelbase | 104in/2642mm | 103in/2620mm | 103in/2620mm | 108in/2743mm |