In 1989, when the Tokyo motor show moved 30km from downtown to Makuhari, the only practicable way from the city (where most of the press and manufacturers stayed) was by train. Which is how I meet Julian Thomson and Simon Cox. As almost the only Caijin on the platform, we struck up a conversation.

I discovered the youthful Thomson and Cox both worked for Lotus as designers. What I didn’t appreciate, until we talked later in the day on the Isuzu stand, was that these two young Brits, then around 30, were responsible for the star of what was later recognised as one of the great motor shows.

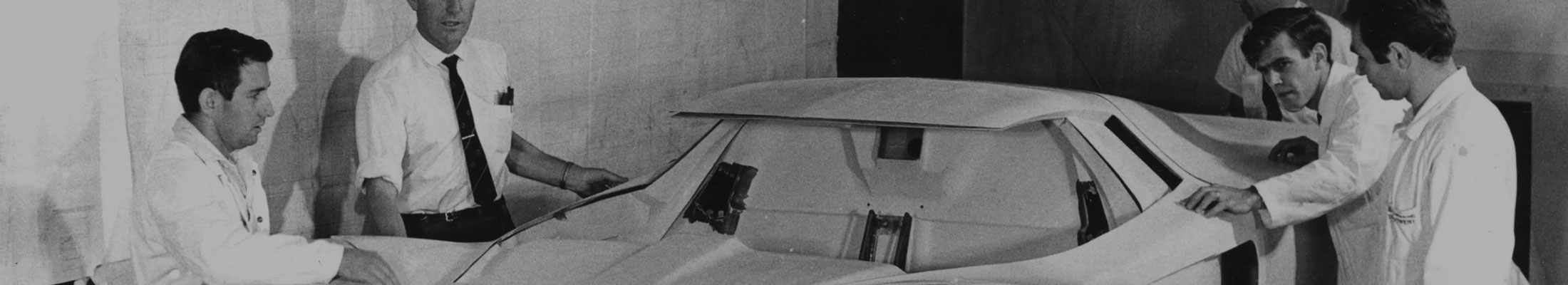

Lotus and Isuzu were then both under the General Motors umbrella. Working under Shiro Nakamura, who ran Isuzu’s Brussel’s design studio and would later go on to a stellar career as head of Nissan design, they were asked to create what became the Isuzu 4200R, a mid-engine supercar, powered by a Lotus 4.2-litre V8 with Thomson responsible for the exterior design, Cox the interior.

Such a car from Isuzu is almost impossible to imagine today, with the Japanese manufacturer (most famous for the Gemini, once Australia’s best-selling small car) now the maker of an only middling range of SUVs and utes. Not so in the 1980s, when Isuzu cars were sold worldwide under various badges. (As well, though few people are aware, the Holden Statesman was sold as an Isuzu in Japan).

Of the gorgeous 4200R, two plus two coupe, Julian told me, “I only did a car like this because I can’t do futuristic ones like the Mitsubishi HSR. I’m not very good at coming up with radically new shapes. I leave that to Simon Cox, who did the interior. What I like doing is classic shapes, well-proportioned with modern touches. I just hope people think it is beautiful.”

So positive was the reaction to the concept car that Isuzu faced immense pressure to productionise the car. Only then did management realised it was a step way too far for the financially troubled car maker. A mere four years later development of all cars ceased and Isuzu was forced concentrated on commercial vehicles.

Following the recent departure of Peter Stephens (who styled the front drive Elan and went on to design the McLaren F1), the two young Poms formed part of what was a revitalised ‘Brat Pack’ of designers at Lotus. In May, 1990, Thomson and a few of his mates (including Lotus chassis engineer Richard Rackham) at Lotus, along with Ghia designers Moray Callum and Sally Wilson, stayed at my Calino, Italy, home. Calino is just outside Brescia, the birthplace of the Mille Miglia and base for the retrospective Mille Miglia. The Lotus Esprit driving Brits then joined a group of Porsche designers, who fashioned fake press passes for their 911s, to run the course with the competing cars. Twenty-five years ago the MM was a highly competitive, if unofficial, road race from Brescia to Rome and return, following the same courses as the original (1927-1957) race. The designers, having found car paradise, couldn’t resist joining in. Today, the retro-MM is far more civilised, more a mobile car museum, than a serious race where the police constantly encouraged you to go faster.

In 1993, when General Motors finally understood tiny Lotus was outside its understanding, Romano Artioli (who also owned Bugatti) bought Lotus. Immediately, Artioli set Thomson, and some outside designers, to work on proposals for an all new Lotus. Their brief was to, ‘realise a car that would revive Lotus with the true ideals of the company’s founder Colin Chapman’.

Thomson’s in-house design easily won the competition. For his Elise, inspired by a Dino 246 GT, he set about creating a car that was as close as possible to a motor bike in terms of simplicity and minimalism. In 1985, when Julian was still working at Ford he bought a red 246 GT at a time when it cost the same as a Sierra, the equivalent of a Mondeo. Smart move. A decent Dino goes for close to half a million dollars today, when a Sierra is virtually worthless. Thomson still owns the Dino – he taught his son to drive in the car – and a Series One Elise, which has also become a classic. With his friend Rackham designing the clever and ultra-light weight extruded aluminium chassis, the little mid-engine Elise was launched in 1996 and remains in production today.

Thomson stayed with Lotus for 11 years, but when it became obvious that Proton, who bought the company from a bankrupt Artioli in 1996, didn’t have the money to develop models beyond evolutions of the Elise, he moved to the VW Group’s Design Centre Europe studios in Stiges, just down the coast from Barcelona. Established in 1994, DCE did concept proposal and production design work for VW, Audi, Skoda and Seat. He survived as head of exterior design at DCE from September 1998 to December of the following year, but was unhappy with the internal company politics (VW eventually closed the studio in 2007) and started to look for an alternative position.

Wanting to return to England, Thomson asked if I could help organise an interview with Ian Callum, who’d recent become head of design at Jaguar. Door opened, Thomson quickly made the move and is now the Director of Jaguar’s advanced design studio. Some months after his appointment at Jaguar Julian, following his thank-you practice of 1990, sent me the drawing – dated November 2000 – reproduced here. No badges, just a discreet Jaguar tag on the huge alloy wheel of what remains a lovely car.

Of car designers, Julian once said, “Our job is to say, ‘What if.’”