by Brian Goulding

For me, the outstanding character in the popular 2019 movie Ford v Ferrari was the cantankerous, ex-patriate race driver and engineer Ken Miles. Actor Christian Bale was Miles exactly as I imagined him to be. The movie was a not very accurate story of how Ford finished 1-2-3 in the 1966 Le Mans 24-hour sports car race. The movie was nominated for four academy awards and featured some great acting performances, most obviously Bale.

Five and a half years before the movie, I wrote a piece on Ken Miles for the ARDC newsletter. I was reading about the development of the AC Cobra for sports car racing in the US and the name Ken Miles kept coming up as the test and development driver. It struck me that I knew little about this driver who played a very important part in the development of three iconic race cars – the AC Cobra, the Ford GT40 and the Ford Mustang GT350.

Ken Miles was born in Sutton Coldfield, UK on November 1, 1918 (10 days before the end of World War I). Before World War II he raced motorcycles and during the war he was in the British Tank Corps where he rose to the rank of sergeant. After the war he raced a Bugatti, an Alfa Romeo and an Alvis at Vintage Sports Car Club meetings before a 1952 move to California to work for the MG distributor.

In 1953 he drove to 14 straight SCCA class victories in an MG special that he built himself. In 1955 he raced a second MG special, “The Flying Shingle” against a rookie in a Porsche 356 Speedster. The rookie’s name was James Dean. By 1956 he was racing Johnny von Neumann’s Porsche 550 Spyder. In 1957 and ’58 he successfully raced a 1956 Cooper fitted with a Porsche 550S engine and dominated the F-Modified class.

Ken’s big break came in 1963 when he was hired by Carroll Shelby. Shelby was transforming the AC Ace by substituting a Ford 260 cubic inch (4260cc) Ford V8 for the Bristol 2-litre 6. After building 75 cars, the better known 289 (4736cc) engine was adopted. The resulting sports car, known as the AC Cobra, certainly needed some sorting out and Ken did a great job. He also raced for the factory team with good results.

At the 1963 Sebring 12 Hours, Miles drove a Shelby Cobra 289 to 11th outright and won the over-four-litre GT class. Interestingly, he was entered as Ken Miles from Great Britain. Later in the same year he finished second in the Bridgehampton 500 Kilometres driving a similar car.

In 1964 he drove Shelby Cobras in four international races. In March he raced a 427 (7-litre) Cobra in the Sebring 12 Hour but failed to finish with engine problems. It was unusual for the factory team to run 427 engines in their Cobras. They did it a few times to develop a 427-powered production car but once it was in production they handed racing of the 427 to privateers. In June, Ken took a 289 Cobra to Mosport in Canada for the Players 200 but was outgunned by the faster CanAm cars. In September, he scored a fine fourth driving a Cobra 289 in the Bridgehampton 500 Kilometres. The year was rounded out by a trip to the Nassau Speed Week with a 396 Ford-powered Cobra. Pole position for the Nassau TT unfortunately became a DNF and the car failed to finish again at the Nassau Trophy one week later.

But 1964 was mainly spent chasing the US Road Racing Championship. Held over 10 rounds at 10 different circuits, Ken Miles (still from Great Britain) won his class (GT over 2 litres) no less than eight times. In those days the American definition of GT was based on units made rather than sports cars with roofs. Hence, the open Shelby Cobras often competed as GT cars.

Things moved up a notch in 1965. After doing a lot of development testing with the American side of the Ford GT40 project, Ken was invited to race the 289 powered GT40 Mk 1. At the Daytona Intercontinental he won with Lloyd Ruby. At the Sebring 12 Hours he was second with Bruce McLaren. Later at the Monza 1000 Kilometres he was third, also with McLaren.

In November 1965, the Shelby organisation took advantage of an opportunity to test a prototype 427 Cobra under race conditions. The race was the Australian Tourist Trophy, which was a fancy name for the Australian Sports Car Championship. The venue was the bumpy, twisting and fast Lakeside circuit just north of Brisbane.

Ken’s Cobra (chassis CSX3002) was a normal 289 with a dry-sump 427 installed. The large oil tank was accommodated in the right hand mudguard (fender). The rear mudguards were ballooned out to cover the wider Goodyear Blue Streaks critical to control the extra power. The car and driver put on a spectacular show, but even with the big engine the production-based Cobra was always going to struggle against the well sorted local sports/racing cars.

Miles faced some formidable competition in the form of Ian Geoghegan and Greg Cusack driving 1600cc Lotus 23Bs and Kevin Bartlett in the Mildren Maserati. Also in the field were Spencer Martin in the Scuderia Veloce Ferrari 250LM and Bob Jane running his Lightweight Jaguar E-Type without its hardtop. In the race the Cobra broke its rear suspension, puncturing a rear tyre, which brought a premature end to Ken’s race. He had been running as high as third. Bartlett also retired. Geoghegan went on to win from Cusack, Martin and Jane.

1966 started well with a win at the Daytona 24 Hours with Lloyd Ruby in a 427 powered GT40 Mark 2. This was followed up by another win at the Sebring 12 Hours again with Ruby, driving the topless GT40 Mark 2 427 known as the GT-X1.

One week later Ken was at Le Mans for the test day, his GT40 Mark 2 427 finishing up second fastest. It was a good and bad day for Ford. The J-Car, the replacement for the Mark 2, was fastest of all but works driver Walt Hansgen was severely injured when his Mark 2 left the wet road and hit a barrier. He died five days later. Ford halted the J-Car test programme until August 1966.

After two years of failure to get on the podium at Le Mans, Ford threw everything they had at the 1966 event. Shelby American entered three 427 GT40 Mk 2s for Ken Miles/Denny Hulme, Bruce McLaren/Chris Amon and Dan Gurney/Jerry Grant. Holman and Moody, the NASCAR people, entered similar cars for Ronnie Bucknum/Dick Hutcherson, Lucien Bianchi/Mario Andretti and Paul Hawkins (Australia)/Mark Donohue. English team Allan Mann Racing also entered 427 Mk 2s for Graham Hill/ Brian Muir (Australia) and John Whitmore/Frank Gardner (Australia). That was a total of eight works Mk 2s, any of which could have won the race. They were backed up by four privateer 289 Mk1s for Jochen Rindt/Innes Ireland, Peter Sutcliffe/Dieter Spoerry, Guy Ligier/Bob Grossman and Skip Scott/Peter Revson. This stellar line up was taking on 14 Ferraris of various types, three long-tail Porsche 906 LHs and a lone Chaparral 2D.

The Fords dominated the race and towards the end they were running a very comfortable 1-2-3. Because the Ford Motor Company heavyweights, including Henry Ford II (and his teenage son Edsel Ford II) himself, were trackside it was decided to try and stage a formation finish for the media. The race organisers threw a spanner in the works when they pointed out that even if an exact three-way dead heat could be organised, the three cars would have travelled different distances because they started from varying distances behind the finish line. Therefore, whichever car started from the highest grid position in the side by side Le Mans start would win the race.

As viewers of the Ford v Ferrari film well know, Miles was ordered to slow down in the lead and let the second and third cars catch up. He did as asked. His light blue car and Bruce McLaren’s black car came out of the last corner side by side. As they approached the finish line Ken eased off to let McLaren take the flag. The story goes that this was his little protest against being told to give up the lead. You can understand that he would not be happy about giving up the triple crown – Daytona, Sebring and Le Mans.

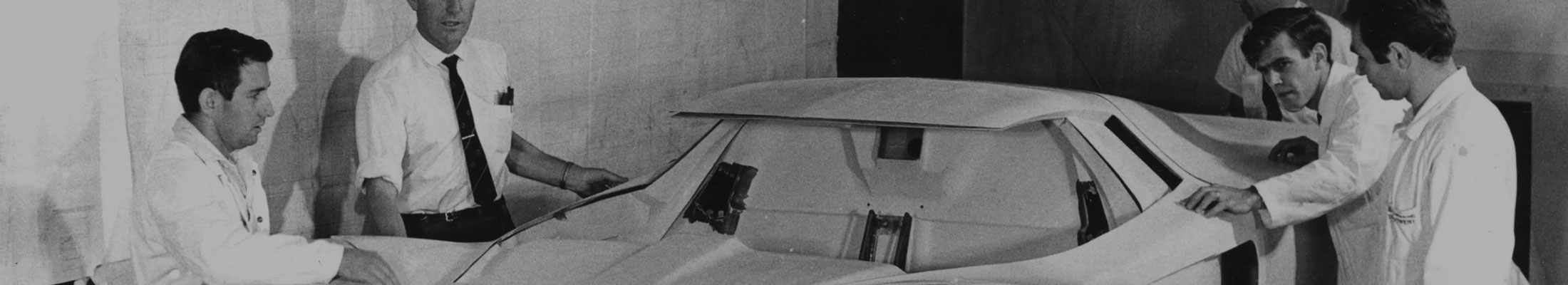

In August 1966 the J-Car testing programme was re-started. The J-Car had a bread van shaped rear end that employed Kamm tail aerodynamics. It also used honeycomb construction, which was supposed to be lighter, stiffer and stronger than aluminium.

At the end of a long hot day of testing at Riverside International Raceway in California Ken was at top speed at the end of the downhill back straight. The J-Car spun, flipped over and caught fire. Ken was killed instantly.

As a result of this incident the aerodynamics were redesigned and a heavy gauge steel roll cage was made mandatory for all new race cars. The revised car was re-named the Ford GT Mk IV and it won the only two races it was entered for – Sebring 1967 and Le Mans 1967.

After this second Le Mans success in 1967 Ford withdrew as a works team. They employed veteran team manager John Wyer to oversee two more Ford victories at Le Mans, in 1968 and 1969, using modified GT 40s called Mirages and 302 (5 litre) engines which conformed to the new rules. Unfortunately, Ken was only part of the first Ford Le Mans victory, but sure as hell he contributed to all four.