Leonardo Fioravanti gripped me by the elbow and steered me to a point diagonally behind the red Daytona. I’d asked, apprehensively, “Is there anything you would change, if you could do it again?”

This question, akin to suggesting another Leonardo alter the Mona Lisa, proposed reworking the voluptuous Ferrari GTB/4 Daytona? All skin-tight curves, every last tissue of its proportions and stance thrusting forward, the engine somehow pulling the wheels far ahead of the cabin to emphasise the seductive sweep from the headlights, across the outstretched bonnet, to the rear quarterlights of its condensed cabin. The Ferrari grille, lower and flatter than it had ever been, almost hidden by the bumper. Change, to this classic shape, a true automotive masterpiece, considered by many to be the definitive front-engine supercar?

The elegant, almost aristocratic, Italian responsible for the design of the Daytona turned, took a short step sideways, crouched down a half a metre or so and nodded, before stepping away and indicating that I should assume precisely the same position. Only then, with me in place, did he speak.

“Now, look,” he said, striding forward while explaining. “The base of the C-pillar should be five millimetres further out. It dips too much, there’s not enough metal.”

He insisted we repeat the exercise at the front, taking even longer to find exactly the right spot from which to view the Ferrari’s nose.

“The side (indicator) lights grow out too much, maybe 50mm,” he growled, his hands marking where the lights should have gone.”

“It’s all I see when I look at a Daytona today.”

Minor flaws pointed out, I can see that Fioravanti is right. They don’t spoil the car – nothing could – but perhaps perfection becomes slightly less so. Despite his reservations, the Daytona is one of the two Ferrari models – of eight he designed – Fioravanti is most delighted to have created.

“The Daytona represents the last of the front engine GT cars, the BB the first of the mid-engine cars. I was deeply involved in the concepts of both cars. I am proud of both.”

For its inspiration, the 1971 BB – more correctly, the 365GT/4 Berlinetta Boxer, Boxer for short – drew on the 1968 P6 and became another definitive Pininfarina shape penned by Fioravanti for Ferrari.

Giorgetto Giugiaro and Marcello Gandini are names familiar to all who know cars. So is Nuccio Bertone and now even Franco Scaglione. Cavaliere Dottore Ingeniere Leonardo Fioravanti never achieved the same prominence. Yet this man, working under the deliberate anonymity of Pininfarina, created some of the most beautiful and influential cars of 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. Anyone who can say of the Dino 246, Ferrari 308GTB, P5 and P6, the Pininfarina BMC 1800 and, of course, the Daytona: “I designed those cars,” has left the world a richer place.

When I first met Leonardo in early 1991 he worked from a frescoed 12th century office in Moncalieri’s beautiful Piazza Vittorio Emmanuel – close to Pininfarina and Giugiaro’s Italdesign – in the foothills surrounding the southern edge of Turin, the home of Fiat and, back then, most of Italy’s famous carrozzeria. Leonardo had gone freelance and was almost finished with an exclusive contract with the Fiat Group. After 24-years with Pininfarina, a year with Ferrari and two years as manager of Fiat’s Centro Stile, Fioravanti, then 55, faced the world as an independent.

Leonardo began designing cars at just 12, even then knowing it would be his life’s work. In 1963 he graduated from Milan’s Polytechnic with a degree in mechanical engineering. It seemed perfectly natural that his thesis was devoted to, “the study of the engine and bodywork of an aerodynamic, six-seater saloon.”

For years he had been fascinated by aerodynamics and the work of Dr Wunibald Kamm. Fioravanti believed Kamm was the only person with any real understanding of how to achieve a truly slippery shape in a car. Kamm’s concept of a sharply cut-off tail appealed to Leonardo and the principle continually appeared in his drawings. Studying under professor Antonio Fessia, an accomplished engineer who, when at Lancia, was responsible for the Flaminia, Flavia and Fulvia, Fioravanti first drew and then crafted in wood a scale model of his advanced sedan.

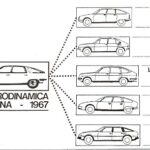

At 25, he obtained his degree and was immediately hired by Pininfarina. Four years later, his barely modified thesis design was presented at the 1967 Turin show as the Pininfarina BMC 1800 Aerodynamica.

To understand the impact you need to rewind your eyes 54-years to an era when virtually all sedans were three-box designs like the Ford Cortina and Hillman Hunter.

The idea of combining a coupe-like sloping tail with a four-door body was novel, even outlandish. All the same design elements from his original thesis concept were there – the complete lack of a conventional grille, the smooth body panels, the multi-curved windscreen, the exaggerated frontal overhangs, the wrap around bumpers and, especially, the chopped off tail. Only the addition of a third rear side window distinguishes the PF 1800 from Fioravanti’s scale model.

He had well learned his aerodynamics. Compared with the production Austin 1800, Fioravanti’s design lowered the cd figure from 0.45 to 0.35. The 1800, and the smaller 1100, should have become new Austins, but BMC was terminally ill and despite public and press enthusiasm for the designs – one magazine wrote: “it seems to demonstrate that so far as styling for the 1970s is concerned, this is the kind of shape we shall all be driving – the BMC’s management stupidly ignored their potential.

It was left to Citroen, with its 1970 GS and 1973 CX, to borrow Fioravanti’s concept and take it to production. In proportions and theme the two Citroens were almost exact mirrors of the 1100 and 1800. Leonardo remembers knowingly turning up at the Geneva’s Intercontinental Hotel, where the GS was announced, and parking the PF1100, which he’d driven from Turin, alongside the Citroen to let the journalists make up their minds about the source of its inspiration. Lancia’s Gamma Berlina, Rover’s SD1 3500 and the Alfasud all display the obvious influence of the PF designs.

A word of explanation here. Where the Daytona was Fioravanti’s personal design, the BMC models owe much to the work of Paolo Martin, another of Pininfarina’s team of brilliant young designers. Martin, just 24 when he designed the BMW 1800 Berlina Aerodinamica, in a team lead by Fioravanti. Sadly, the two men seem to have fallen out. Martin makes no mentioned of Fioravanti in his book Martin’s Car; Thoughts in Three Dimensions (2017).

A word of explanation here. Where the Daytona was Fioravanti’s personal design, the BMC models owe much to the work of Paolo Martin, another of Pininfarina’s team of brilliant young designers. Martin, just 24 when he designed the BMW 1800 Berlina Aerodinamica, in a team lead by Fioravanti. Sadly, the two men seem to have fallen out. Martin makes no mentioned of Fioravanti in his book Martin’s Car; Thoughts in Three Dimensions (2017).

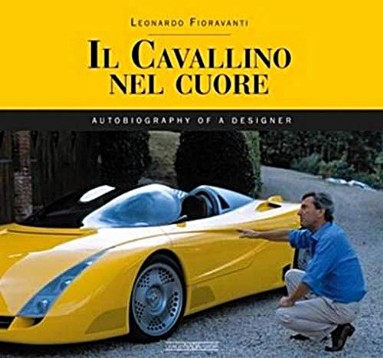

In Il Cavalino nel Cuore: Autobiography of a designer, Leonardo says, “I chose Paolo Martin, one of the brightest of the young intake, to materially create the sketches and lines drawing. He also contributed an innovative solution for the rear lighting cluster, inserting in a hollow “transom” rear panel.”

It seems Fioravanti established the basic design, but the details of the BMC designs were Martin’s, as developed under Leonardo and his boss Franco Martinengo. Martin, who claims the elegant Fiat 130 Coupe (and the less than-elegant Rolls-Royce Camargue), Lancia Beta Monte Carol and the Peugeot 104, as the best of his other PF production designs. After a period at De Tomaso , Martin worked as a freelance designer, and even styled a still-born four-door sedan for Lotus.

Fioravanti’s other achievements came quickly – helping Aldo Brovarone with the 206/246 Dino, and the next year, at just 30, the 1968 Ferrari P5 and P6 plus, of course, the Daytona.

At the 1965 Paris salon Ferrari showed the 275GTB, a classic drop-nosed front-engine GT car with faired headlights, a deep wrap around windscreen and short tail that hinted at a spoiler. It was an instant hit and surely destined for a long model life. Until in December 1966, Fioravanti displayed the full measure of his inventive flair.

“We had two bare chassis, complete with engines, for the 330 GTV and 275GTB. I’d never seen them before like that,” he remembers. “There was no plan for a new car. Today, I still don’t know why, but when I saw them I had an incredible idea. I thought what we had made before was completely wrong. I realised there was a new car up here,” he told me, pointing to his head. “It was not a repeatable moment. I worked for a week without a break. I showed it to Sergio (Pininfarina) and asked, ‘Why not make a Ferrari like this?’ It was a moment of pure creativity.”

Fifteen months later, at the 1968 Geneva motor show, Ferrari unveiled the Daytona, and the 275GTB was instantly obsolete. The 365GT (later the 400i) was present a year later. By 1972 Fioravanti was director of design at Pininfarina and later managing director.

“Hard work,” says Leonardo, “Is not a matter of time, the number of hours, the time you come to work. It is the tension, the density of work. I don’t like to work 12-hours a day. But when you have a target, an objective, at this moment you need to have maximum effort, the concentration of creative work. When you have finished you are destroyed, you don’t want to see it again. It is only when you see the car after 10 years that you remember it sentimentally.”

There is a comfortable self-confidence about this man that some might mistake for ego. He knows he has a talent, a rare gift for the truly new, and is fascinated by the concept: “I’m interested in ideas” he argues, “In my long career, I realise very few people are at the origin of ideas. I was asked by an English magazine to name the most important car in history. That’s easy: the first.”

“My object is to explore this field (of ideas) and to realise the minimum number of people for the maximum number of projects. For this purpose you need no more than 10 to 20 people. With today’s computers that is enough for one leader to do a new car.

“There are many good design schools, but they can only refine natural capabilities. It’s possible to teach, but the schools don’t create ideas.”

Fioravanti’s work at PF didn’t just involve Ferrari for he can also claim credit for two of the most attractive European cars of the 1980s: Peugeot’s hugely successful 205 and Alfa Romeo’s beautiful 164. Both display the timeless proportions and simple lines that have always been traits of Pininfarina design.

When interviewed in 1992, a copy of La Maccina Che Ha Cambiato Il Mondo – The Machine that Changed the World – the significant 1991 book based on the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s (MIT) five-year study on the future of the automobile, and especially Toyota’s lean production system, sat prominently on Leonardo’s desk. My noticing the new book immediately led to a conversation about Japanese cars and, following the successful launches of the Mazda MX-5, Lexus LS400, Nissan 300ZX, and the Infiniti brand, the generally accepted view that the Japanese car makers were about to conqueror the automotive world.

Fioravanti, having worked for Japanese companies from as early as 1979, was familiar with, especially, Honda’s work processes. Starting with Akai and Honda, for whom PF made a number of proposals during the 1980s and 1990s, although only the 1984 mid-engine HP-X was ever made public. (later, after Fioravanti left PF, Honda showed the 1995 Argento Vivo, a precursor to the 1999 2000 roadster)

.

“We Europeans have the possibility to resist the Japanese,” Fioravanti told me. “But from the possibility to the reality is not the same thing. We are more serious with our projects, somehow less marketing oriented.

“The Japanese produce cars that after two years we don’t remember. I am not sure if their policy of continual renewal is the right way. There is an exaggeration of models and changes in models, without true novelty content. It is the details that are constantly being changed. People don’t need a new car every year, but a good car for some years. I doubt the Japanese system is in line with the future needs, the reality of the customers. This must change.”

Lured away from Pininfarina by Enzo Ferrari and Fiat Auto boss Vittorio Ghidella in early 1988, Fioravanti left Pininfarina to take up the position of assistant general manager at Ferrari and managing director of Ferrari Engineering. The promise was that after gaining suitable experience, and after the old man (then 90), died he would run Ferrari for Fiat. Enzo believed Fioravanti, better than anybody else, understood what a Ferrari should be. Leonardo was his successor. Ferrari died soon after in August 1988 and Ghidella suddenly and unexpectedly left Fiat Auto in 1990. The internal politics at Maranello changed radically and Fioravanti moved to Fiat’s Design centre, becoming general manager of Centro Stile Fiat Auto in 1990. Less than two years later he had gone freelance. It’s clear, in talking of these events, that Fioravanti is disappointed his role at Ferrari came to a premature end.

“Working with Ferrari was the dream of my life,” Leonardo explained. “I knew Ferrari from the 1960s and understood that at Ferrari the difference between management and design is not so divided. At Ferrari the philosophy is the most important thing. If you can generate the right philosophy, it is the philosophy of Commendatore Ferrari. The top man needs to think product”.

After leaving Fiat in 1991, Fioravanti moved full-time to the architectural practice he founded in 1987 while working in Tokyo, and focused his work solely on prototypes, concept cars and hybrid vehicles. The design studio is where he gets to live his childhood dream.

“For me, it is always function first,” said Fioravanti, who has a liking for Japan, having worked with Honda and, later, Toyota and Lexus on their most iconic models. At the 2005 Detroit show, Lexus displayed the first of three LF-A concept cars before the production version finally appeared at the 2009 Tokyo show. What Toyota didn’t admit was that the 2005 car showed a strong European influence. A little research in Turin revealed that the LF-A was one of a number of Lexus concept cars and proposals designed by Fioravanti in Turin.

Asked about the connection in 2005, Leonardo would only admit, “Like any freelance designer, by contract I cannot comment on a specific project. But I cannot deny I’ve been working for the Toyota Motor group in recent years.”

The many celebrative photos taken of Fioravanti and the LF-A concept by Lexus top executives said far more than public statements. There is also the fact that LF- is also Leonardo Fioravanti’s initials as well as meaning, in Lexus-speak “L (Lexus)-Finesse”. Toyota says this is purely coincidence.

Fioravanti began his association with Toyota with the seventh-generation 1999 Celica coupe. That car resembled the F100 concept car he designed in 1998, though he always denied involvement in the Celica project.

In 2008, his company Fioravanti Srl produced a special coachbuilt Ferrari under Maranello’s ‘Portfolio’ program, the model being based on the F430. More recently he formed a partnership with a Shanghai-based design and engineering consultancy with the aim of delivering a wide range of design and engineering services for Chinese carmakers.

“The love of cars keeps you young,” said Fioravanti, a self-avowed optimist (“The good men in the world always outnumber the bad”), who believes in technology’s power to make the world a better place. In future Robbo Archive tales, I shall tell the story of Fioravanti’s obsession with the headlight as a design feature and his driving a VT Commodore SS in Italy.