by Peter Robinson

Luca di Montezemolo delivered his last address to invited journalists at the 2014 Paris Motor Show. Elegant, as always, in a grey suit, his legs crossed, his black socks visible as he sipped Italian mineral water from a wine glass, the tension between Montezemolo and his boss Sergio Marchionne was obvious. This was a mutual display of overt hostility.

Marchionne in his typical pullover, walked into the presentation of the Ferrari’s new 458 Speciale late. There was no acknowledgement as he walked across to his subordinate, before sitting at a desk a few metres away. Marchionne’s bored pose said it all: his chin resting on his elbow as Montezemolo addressed the journalists.

“This is at least for me an important day, as it is my last meeting with you,” Montezemolo said. “And, you know, the life is strange, and life makes surprises to each of us. What is important is to learn and look ahead.”

In a show of flagrant disrespect, Marchionne turned his back on Montezemolo and began examining a book of leather samples.

The controversy was fuelled when Montezemolo, responding to the question: why was he leaving Ferrari?, winked and pointed directly at Marchionne.

“If you have three hours, I will explain,” he joked.

“After 23 years, we are in front of a new era, because for sure this will be a new era with the group, with the flotation, it is time to leave, even because at the end of the day I am at the end of my long and fantastic trip inside Ferrari.”

Marchionne butted in when the issue of Montezemolo’s departure continued to be debated.

“There is not a single doubt in my mind that his departure is not as glorious as you want to make it,” Marchionne told the media.

“We can build a whole pile of hypothesis and conjecture; at the end of the day, I think Luca and I have come to the conclusion that, as a result of the flotation of Fiat-Chrysler in the US, this is opening up a new page in this organisation.

“Luca has had a phenomenally impressive career within Ferrari; he’s been the chairman of Fiat for a period of six years; was on the board with me for 12; he has been an integral contributor to the resurrection of Fiat and has done a tremendous job of leading Ferrari.

“Whatever it is that you’re hearing, these whispers – absolute bullshit. Shut off the radio cause you’re listening to the wrong station.”

Montezemolo claimed he did not know what he was going to do post-Ferrari and it was clear that neither he nor Marchionne were prepared to give a direct answer as to why the man who rebuilt Ferrari ended up departing.

Luca di Montezemolo has come to terms with life after Ferrari, yet the pain of his September, 2014 firing hasn’t gone away. Talk Ferrari and it’s obvious the anguish, the unfairness, remains.

Along with the charm, the friendly greeting, the elegantly informal clothing, the longish hair, the constant hand movements, the enthusiasm, the piercing blue eyes, and the quick assessment and understanding. Even if, at 74, Montezemolo has perhaps lost five percent of the dynamic energy that makes him one of Italy’s most successful business tycoons.

In the eight years since that fiasco Montezemolo couldn’t bring himself to speak of the circumstances of his final weeks as chairman of Ferrari, where he reigned supreme for almost 23-years.

“Please, how it ended I cannot really talk about,” Montezemolo told Mark Hughes, the much-respected F1 journalist, in 2016.

When last I interviewed LDM – as he was always known to the British press – in May 2014, I asked about a succession plan, deliberately avoiding the retirement word.

Instant serious voice, “Sure, it’s very easy,” he replied. Then the Hollywood smile, “It will be myself. There are still many things to do: we are always looking ahead.”

Only now is Montezemolo ready to clarify his understanding of the motivation behind his sacking. A dismissal that came just six months after he renewed his three-year contract.

x – x – x – x – x

We meet in the board room of Luca Montezemolo’s Rome offices in the posh Parioli area of Rome, just north of the Borghese Gardens. I’m astonished there is nothing in the elegantly furnished room to hint at LDM’s involvement with Ferrari: eight chairs are neatly arranged around the central table, the shelves house art and travel books, a glass box on the table is filled coloured pencils, there’s also small clock, the room dominated by a huge photograph of a desert. Ironically, the only allusion to cars is a silver, generic model of a 1950’s F1 car that might be a 250F Maserati. Nothing personal. Zero.

“Forget Ferrari, we speak (of Ferrari) later,” he says, immediately launching into a review of Ferrari today.

“Ferrari is already another Ferrari, they talk of electric cars and SUVs – I don’t like the name (Purosange) – I think they are terrible, but this is not my taste. They have become a mix between a financial company, so the shareholder value is the priority number one, and a supercar manufacturer and are very busy with work on the electric car.”

Montezemolo intended Ferrari’s FF, the 4wd two plus two released in 2011 to fulfill the role of an SUV. When LDM ran the company, his view was simple, “Ferrari fanatics have to survive without an SUV.”

Nor, now that an SUV is inevitable, does he like Ferrari being the last participant in super-opulent SUV segment.

“I don’t like that they are last behind Porsche, Bentley, Lamborghini and Maserati. I preferred to be the first,” he says, siting the introduction of paddle shift automatics, wholly composite materials, and Italy’s first hybrid (LaFerrari) during his reign.

“I think Ferrari makes an SUV mainly for commercial reasons. That is good, they are a public company. I don’t like to talk about something I don’t know, but from what I’ve seen the Ferrari is more close to the Lamborghini; expensive, very powerful, with far more (profit) margin. Of course, they will call it something different, not an SUV. Anyway, it’s marketing. To increase turnover, sell more cars, and already they are at 11,000 (a year).” He agrees that with the Purosange annual sales could rise to 15,000 cars.

“They have increased the number of today’s models, a lot of one-offs, they have improved the turnover and have different strategies, different priorities, different ideas, and new management that has not (previously) been involved with cars. They become public and this is the reasons they have a lot of new models.”

Montezemolo fought against Ferrari going public and today contends that the 2015 decision saw Ferrari “became the Bancomat of Fiat Chrysler.” The money raised was used to fund the latest Alfa Romeo revival and pay down FCA’s debt. The initial public offering to sell shares at $(US)52 saw the shares rise to a high of $(US)274 in November 2021, before settling back to today’s $(US)192 to give Ferrari a capital value of a staggering $(US)37billion.

Snatching the chance to interrupt his flow, I ask why there is nothing personal on the meeting room, nothing to link LDM to his two periods with Ferrari, the first from 1974-1976, when his ran the hugely successful F1 team, and the second from late 1991 to 2014.

He laughs. “Okay, okay, why don’t we go to my office? It’s very close.”

This room is smaller and far more personal, the workplace of a man who is proud of his achievements, the walls lined with photographs and memorabilia that reference life with Ferrari: a photograph of Lauda’s last lap at Monza in 1975 when his third place gave him the world championship; Jean Todd and Michael Schumacher with LDM after winning the titles in 2000; the Forbes magazine cover featuring Montezemolo; a 1950s Fiat Multipla “the first MPV” model; the front page of the October 9, 2000 La Gazzetta dello Sport, Italy’s most popular newspaper, headlined “Grazie Ferrari” when Schumacher won the championship for Ferrari.

Most significant is the farewell present from the 4500 Ferrari staff: a red, metre high tower, faced by 60 individual photographs of his Ferrari career highlights, the base reads “Luca 60 Veni, Vidi, Vici”.

Okay: Why did Montezemolo leave Ferrari?

The most frequently cited suggestion is because Ferrari’s Formula One team hadn’t won a championship since 2008 and achieved just two podium positions (to September) in the 2014 season. Given that the F1 globe (at least in Italy) revolved around Maranello that seemed to be the most prevalent theory.

The official reason seemed to be the one provided in the first part of Montezemolo’s departure statement: “Ferrari will have an important role to play within the FCA Group in the upcoming flotation on Wall Street. This will open up a new and different phase which I feel should be spearheaded by the CEO of the Group.”

That, of course, refers to FCA chairman Sergio Marchione who, to no one’s surprise, replaced Montezemolo as Ferrari chief after the two executives had been at loggerheads for a couple of years before the sacking.

Says LDM today, “I was totally against the idea of the flotation for the simple reason that a flotation means you lose control. The (Agnelli) family wanted to take money from Ferrari – Ferrari’s value was higher than the entire FiatChrysler group – and (going public means) you become a different company that is obliged to grow. I wanted to maintain an exclusivity and very, very high positioning to maintain a unique brand. I wanted to grow in terms of technology, in terms of design and overall innovation, which I think I demonstrated. Marchione (who died suddenly in July 2018) was the CEO of every FCA company, Alfa Romeo, Dodge, Chrysler, RAM, Fiat, everything, and (John) Elkann (the grandson of Gianni Agnelli) was chairman. But not of Ferrari. They wanted to get me out of the company. I was too much independent.”

Was the failure in F1 another reason?

“They told me I made a very good job of the road cars, but there is only one small problem, that we lose (in F1).”

“The heart of Ferrari is winning in Formula 1,” Marchionne said during a defensive press conference held to announce the departure of Montezemolo. “’I don’t want to see our drivers in seventh and 12th place. To see the Reds in this state, with the best drivers, exceptional facilities, engineers who are really good, to see all that and then to consider we have not won since 2008 . . . the important thing for Ferrari is not just the financial results, but also it is winning, and we have been struggling for six years.”

Just days after the 2014 Italian Grand Prix, where Kimi Raikkonen’s Ferrari finished ninth and Fernando Alonso retired with engine failure, and a week before the Paris show, LDM was fired in a tense meeting with Marchione and Elkann.

In his defence, Montezemolo points out that Ferrari won 14 titles during his time as CEO of Ferrari.

“We lost the championship at the last race in ’97, ’98 and ’99, so from ’97 to 2004 we either won the championship or finished second. We lost the championship unbelievably on the last corner in 2007 and won in 2008. We lose again in 2010 and 2012. So Ferrari was on top or almost and we fought with many rivals: Williams and Red Bull and McLaren and Renault and Mercedes. So many teams.”

“Yes, he says in answer to the inevitable question, “I still watch Formula One with passion and love, but with less stress.”

Left unsaid is that Marchionne’s clear objective to get Ferrari back to the top has yet to eventuate. Since 2014 there have been three seasons without a win and no titles, Ferrari finishing a dismal sixth in the constructor’s championship in 2020.

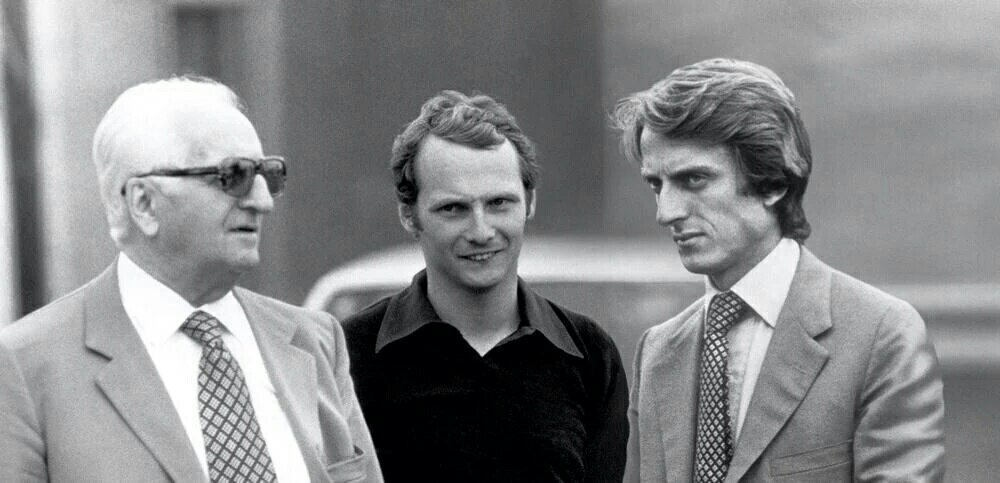

It was a similar poorly performing Grand Prix team when Montezemolo joined Ferrari in 1974, at just 26 years old and fresh from Columbia University in New York. With Niki Lauda he reorganised the F1 team and garnered two driver’s world championships and three constructor’s titles between 1975 and 1977. He then moved on to other positions within the Fiat empire, running Italy’s World Cup in 1990.

The call from Fiat boss Gianni Agnelli came late in 1991. Piero Fusaro, Ferrari’s then president, had been banished to another part of the Fiat empire and Alain Prost had been fired.

In To Hell and Back, Niki Lauda’s first book (1985), he wrote, “Luca Montezemolo, Ferrari’s team chief, was a fully fledged protégé of the Agnelli (Fiat) dynasty: he was very young but he was good. Because of his social background he was largely proof against the daily intrigue, and this meant he could concentrate on the real job at hand, something of a privileged position for a Ferrari team chief. Off the top of my head, I can’t think of anyone in that position before or after who enjoyed the same freedom.”

That freedom, the ability to rebuild Ferrari, to rejuvenate the F1 team, plough money into Ferrari’s increasingly vertically integrated industrial complex, and turning out a succession of great road cars, continued throughout his time in Maranello. At least until the once tight bond with the Agnelli family was blown apart by John Elkann who, says LDM, was “fully aware of my relationship with his grandfather (Gianni Agnelli died in January 2003).”

It was the Avvocato Agnelli who commissioned a one-off Ferrari 360 Barchetta as a wedding present for LDM’s second marriage in 2000. It’s now the only Ferrari in Montezemolo’s garages (they also house a Renault Zoe, Fiat Panada, an old L-R Defender and Range Rover and Fiat Campagnole (off roader), as well as the electric bike he rides to work in Rome.

On a highly emotional October day in 2014, flanked by vice-chairman Piero Ferrari and CEO Amedeo Felisa, the King of Ferrari thanked the over 2000 workers who turned out to say farewell. LDM admits, “It was a fantastic day, I will never forget in my life. They were crying, I was crying. We were all crying.”

Time to move on from this painful episode. What of the rumours of Montezemolo’s involvement – as a consultant? – at Aston Martin, now effectively owned by Canadian billionaire and Aston chairman Lawrence Stroll? Was LDM behind the move by Amedeo Felisa, former Ferrari CEO, to become CEO of Aston, and ex-Ferrari chief engineer Roberto Fedeli to his position as Aston’s new chief technical officer?

“As always, the truth is in the middle,” says Montezemolo. “I am a long-time friend of Lawrence Stroll. He is maybe one of two people in the world who own two GTOs, he used to race in the Ferrari Challenge and became a Ferrari dealer in 1993. He is very rich and has a big, big passion for Ferrari and a huge collection of cars, so we became friends.”

In 2010 Luca Baldisserri, who ran Ferrari’s Driver Academy, told Montezemolo about this phenomenal 11-year-old Canadian kid who turned out to be Stroll’s son Lance. “I called Todt, but they said 11 was maybe too early. Anyway, we hired the boy (into the Academy). He raced in F3 and then went to Williams, financed by Lawrence who wanted to give his son the possibility to enter in F1”.

“Just before Aston Martin’s float (in 2018), I was approached by a large bank and asked if I would be interested to be chairman and CEO of Aston Martin. I say no. Maybe if I say yes, it would be good for the value, but I say no”.

At around the same time Stroll bought the Force India F1 team which soon became Racing Point. However, overwhelmed by debt, it dropped out of F1 at the end of the 2018. Stroll’s F1 ambitions didn’t die.

“I told Lawrence, why don’t you talk to this bank about Aston Martin. Lawrence decided he wanted to buy Aston Martin and take them back to F1.” When Stroll’s consortium took control of A-M in early 2020 he hoped to appoint Amedeo Felisa, who retired as CEO of Ferrari at the end of 2015, as chairman. It was too early for Felisa, who was chairman of the Montezemolo controlled Atop, a manufacturer of electrical automotive components.

Two years later, unhappy with Tobias Moers’ management of Aston, Stroll again approached Felisa, who told LDM. “He is pushing me, he’s not happy with the CEO and wants me to accept to be CEO.”

“So, nothing to do with me,” says LDM seriously.

Post-Ferrari LDM remains incredibly busy. He was off to Abu Dhabi for a couple of days 24-hours after our meeting. Montezemolo’s success in running Acqua di Parma, Confindustra (Italy’s industrial confederation) and the creation of NTV-Italo, Italy’s private high speed train company, Charme, the private liquidity company run by his son Matteo in London, and most recently Toscano, Italy’s cigar company (most famous for Clint Eastwood’s rustic cigars in his Spaghetti Westerns), are a tribute to his ability to combine entrepreneurial creativity with pragmatic solutions, great organisation and the capacity to choose the right people.

Yes, there have been failures: Alitalia, Italy’s national airline, and not even Montezemolo could make a success of Maserati, which Ferrari ran from 1997 to 2005 before passing it back to Fiat. Over the years I’ve learned he could be ruthless one minute and turn on the charm within seconds, for he loved talking to journalists.

Two years ago, LDM was approached by an important American publisher keen for Montezemolo to write an autobiography or at least to do an ‘interview’ book with leading journalists. “I say no, sooner or later I will do it”, he pauses, “I don’t feel old enough to do a book on my life. And there is another project involving an American movie producer who is thinking to do a movie on my life.

One week before our meeting, journalist Bianca Corretto, writing in Corriere della Sera quoted Marchionne as telling her a few weeks before he died, “I made a big mistake in to let Luca go.”