by Peter Robinson

Pista di prova di Nardò della Fiat – say it out loud – resonances rather more romantically than the translation to Fiat’s Nardo Test Track.

Seduced by the evocative title, I vowed to visit the place from the moment the world first heard of Nardo’s incredible 12.6km circular track, a high-speed bowl so vast it’s capable of a hands-off steering at 240km/h. That was back in 1977 when I lived in Sydney and edited Wheels magazine. A little over a decade later, I moved to Italy to work as European Editor of Autocar. Enticed by former Wheels colleague Mel Nichols, Haymarket’s Editorial Director, Mel dictated only that we live somewhere on continental Europe. It was always Italy: for the food, the culture, the people, the weather and, not least, the cars. We came for two years and stayed for 16.

I’m now embarrassed to admit that during that time I never travelled south to the Puglia region, where Nardo is located on the heel of Italy. This, despite being fascinated by ongoing stories from engineers, drivers, and other journalists of numerous Nardo record attempts. Finally, I learned a Continental Flying Spur lapped Nardo at an indicated 320km while effortlessly hauling four English motoring journos in Bentley-opulence.

Too much. I needed to make good on my promise of 31-years. The excuse for a story: wanting to be among the first to try Nardo’s newly opened, much praised, 6.22km handling track.

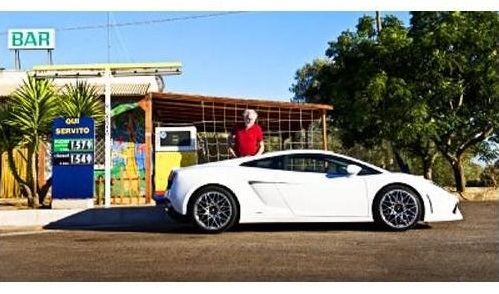

To do justice to the 2000km journey to Nardo from our home near Brescia and back to Modena, clearly only an Italian supercar would suffice. Why not Lamborghini’s recently revised LP560-4 Gallardo?

Under Audi’s ownership, the Sant’Agata Bolognese factory presents a modern glass complex to the world, hiding the old yellow assembly plant and offices from outsiders. I first came here in 1982. Now, instead of walking straight up to see Ublado Sgarzi, Lamborghini’s Mister Fix-it or, later, Sandro Munari, the first world rally champion, now turned always worried Lambo PR-man, you sign in and hand your passport to one of three women at reception.

Test driver Moreno Conti presented our white Gallardo, and it was only a matter of minutes before I began relishing the instant responses and evocative sounds of the normally-aspirated 5.2-litre V10.

I specifically remember struggling to adjust to the clunky paddle-shift gearbox and the too-slow-to-engage and grabby carbon brakes. On the heavily-policed autostrada north of Pescara, it seemed Italian drivers had finally learned to obey the 130km/h speed limit. Further south, as traffic thinned, speeds rose and we enjoyed the melodious induction sound that kicked in like you’ve turned a switch at 3800rpm. Welcome to old-style Italy and 200km/h cruising.

We stayed overnight near Nardo, ensuring our Lambo was secure in the underground park. The following morning on the drive from our hotel to Nardo, my photographer mate Tim Wren wanted to know more about the place. I’d done my research: it was engineer Osco Montabone who convinced Fiat that a circular track was central to an automotive proving ground. Almost from the moment it opened in July 1977, Nardo became home to speed record breakers and witnessed stellar successes and disasters.

A Mercedes C111 reached 403.978km/h in 1979; a Porsche 928S averaged 251.4km/h while covering 6033kms in 24-hours in 1982; 11-years later another 928 upped this to 265.72km/h. This was utterly smashed in 2002 by VW’s Concept W12 Nardo. Helped by a horde of Volkswagen engineers and a rotation of seven drivers, Ferdinand Piech’s still-born VW supercar covered 7749kms in 24-hours, averaging a mighty 322.9km/h. It’s a record that, I believe, still stands today.

In a supposedly secret test in the early 2000s, celebrated Bugatti (and Lamborghini and Pagani) test driver Loris Biocchi lost a tyre, his visibility and his brakes at 398km/h in a Veyron prototype. Loris’s instinct steered him into the guard rail and, eventually, after damaging 1.8kms of guardrail, the Bugatti stopped.

By the 1990s, after a decade of short-sighted neglect by Fiat, Nardo was sold to Prototipo, a Turin-based engineering firm. Prototipo added new tracks and expanded the workshop facilities but didn’t have the financial resources to further develop the site. What customers like Audi and Porsche needed was a specific handling track. Prototipo planned a mini-Nordschleife, but the firm ran into trouble when Fiat’s two-year guarantee of work ran out. In 2002 Nardo was bought by the Allianz Group. Investment followed and by the time of our visit in 2008, Nardo employed over 100 people with 400 car-maker engineers on site most weeks.

In 2012, Porsche bought Nardo from Prototipo for an undisclosed amount and boasted that, “Thanks to its mild climate, Nardo can be used throughout the year in three shifts around the clock, seven days a week”.

Surely, I wondered at the time, Ferrari was approached? According to Luca Montezemolo, Ferrari’s former chairman, “Ferrari didn’t consider to buy Nardò.” Understandable, when Ferrari has Fiorano and Mugello.

Absurdly, this four-lane circle, set in 700 hectares among ancient olive groves and unspoiled villages, can be seen by the naked eye from space. NASA sites Nardo as one of the few man-made objects, along with the Great Wall of China and the Pyramids of Giza in Egypt, that shares the honour. To put Nardo’s enormous 16-metre-wide bowl into perspective, the old Holden speed bowl at Lang Lang was just 4.7km.

Nardo is now screened behind 40km of 2.5-metre-high concrete wall. It works: scoop photographers have mostly given up using it as a lucrative location. To enter the proving ground you drive under the bowl, and immediately become aware that most of the inner area remains farming land.

For our visit the various car makers on hand were told a journalist and photographer were there on official business. We gave our word not to snap any of the still-disguised, clearly visible, prototypes. What was equally obvious is that in a world where supercars are the norm, the manufacturers weren’t concerned about rivals seeing their new models two years before launch. Seems there is an unwritten etiquette between the engineers not to photograph competitor vehicles.

All have large individual garages some with long term contracts: when Porsche signed on for 12-years in 2007, it built four workshops. Apart from the weather, the attraction is a brilliant facility that includes virtually everything necessary to develop and test a supercar (or any car). Today, Nardo provides the ability to test fast-charging of electric vehicles, autonomous technologies and vehicle-to-vehicle communications.

Somehow we negotiated a small slot on the handling track. An hour cost $350 in 2008, Porsche won’t say how much today, only that “It’s approximately the same.”

This is a seriously fast track, 10.5metres wide, with significant elevation changes (like all good tracks), seven bends to the right and nine to the left, making it a truly exciting and a marvellously hard-to-learn challenge. One the Gallardo willing accepts. The Lambo, so planted it was impossible to get the tail to move out, even at full noise in second gear through the slowest corner, lifting mid-apex. Instead the Gallardo, I remember all too clearly, shifted into understeer from which there was no escaping.

Down the kilometre long straight we topped 250km/h before briefly braking for a long, left-hand sweeper that I managed to consume at 200km/h in fourth. Gentle turn-in, a tad more lock than expected and the car slices through the corner. For braver drivers than me, it would be flat in a modern supercar. No questioning the Gallardo’s stability or speed, only that in a constant understeer fight, it lacked the poise and balance of Ferrari’s F430 rival. All wheel drive ensures great traction: my preference is for greater agility and handling adjustability.

Easy to see why Porsche and Ferrari test drivers love the flowing nature of the track – I shouldn’t call it a circuit, for it doesn’t have FIA approval for F1 testing. We’ll know the VW Group is getting into F1 when the handling track is signed off by the FIA. Equally, I suspect even the best drivers lift for a spectacular hump – memories of the ‘Ring – that instantly hurls a fast car into space. In 2008 the ‘unofficial’ lap record of 2 minutes 43 seconds, an average of 137km/h, was held by a 430 Scuderia. No such record exists today, according to Nardo and an assortment of test drivers. I don’t believe

them.

Aston Martin had booked the bowl for an hour for exclusive use at lunchtime, but we managed to sneak a few laps before the others returned. Speeds of up to 240km/h are allowed in general use, genuine high-speed testing demands the bowl is restricted to one car manufacturer.

So vast is the diameter on Nardo’s mildly angled top lane that at 200km/h the circle feels like a super-wide motorway sweeper. Snap-changing up through the gears at 8400rpm, the sounds of speed, tyres and engine and, especially, the impression of velocity, are diminished by the width of the track. Even 250km/h is a doddle. My notes reveal that at 280km/h the Lambo began to move around on the bumps 31 years of testing had provoked. As we top 300km/h, throttle hard against the footwell, the Gallardo was being punished by the lumps, the feeling of stability ever reduced.

In 2019 Porsche invested 35m Euros (A$56m) to completely resurface the bowl, install a new guard rail designed specifically for Nardo by Porsche Engineering, and completely renovate the facility.

In Porsche’s own words, development as an R&D centre is “continuously ongoing,” to ensure that the Porsche Engineering can meet the needs of around 90 automotive clients that include all the VW Group brands – including Scania and Ducati – but also BMW, FCA, Mercedes-Benz, Jaguar, Land Rover, Aston Martin, Maserati and Ferrari (for maximum speed tests).

Nardo? Brilliant, challenging, contradictory (like Italy) – driving heaven.