On learning that 88-year-old Nino Vaccarella died on September 23, I smiled quietly to myself. No, I’m not callous. I smiled because I was instantly transported back to that March day in early 1992 when Nino and I drove the Targa Florio course. If there has been a better day as a motoring journalist, I don’t remember it. Of course, I smiled.

“I have driven the course a thousand times,” Nino told me. “I know every corner. Every tree, every stone tells me whether a corner is narrow or wide, if it goes up or goes down. Every centimetre I know.

“I have driven the course a thousand times,” Nino told me. “I know every corner. Every tree, every stone tells me whether a corner is narrow or wide, if it goes up or goes down. Every centimetre I know.

“How many corners? Five, six hundred…the Targa Florio is all corners,” he laughed.

Fifteen years after Nino Vaccarella last raced around the 72km circuit of public roads, he still had total recall of the Circuito Piccolo delle Madonie. Back then il preside volante (the flying headmaster) from Palermo took on the world’s best drivers and beat them in his own backyard, using his knowledge and not a little driving skill so well that his name became synonymous with Sicily’s great race. You heard about the Targa Florio and you thought of Nino Vaccarella.

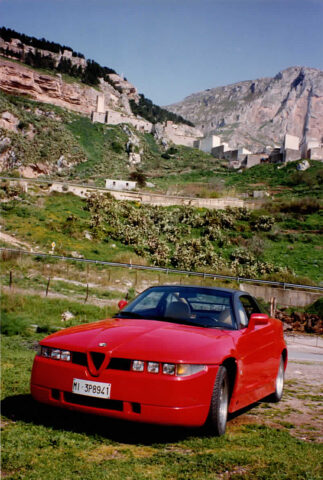

“Here we can go fast,” Nino dropped down a gear and accelerated hard past a 50km/h sign and towards the blind right-hand hairpin. Beyond the guardrail there’s a hideous 250 metre drop, and the road is narrow and craggy, pitching the Alfa in two directions at once.

Vaccarella is unconcerned. Sure enough, the corner opens up. Our Alfa SZ could have gone through at twice the speed. Within 100metres, Nino proves his claim. To me this corner looks identical to the last, the same crumbling stone wall on the inside, a cypress tree clinging tenuously to the edge of the road on the outside of the guardrail.

Vaccarella is unconcerned. Sure enough, the corner opens up. Our Alfa SZ could have gone through at twice the speed. Within 100metres, Nino proves his claim. To me this corner looks identical to the last, the same crumbling stone wall on the inside, a cypress tree clinging tenuously to the edge of the road on the outside of the guardrail.

“This one is slow, no?” he asks, squeezing firmly on the brakes, shuffling the wheel urgently. The corner is tight, one hairpin followed immediately by another. It’s no place to go quickly.

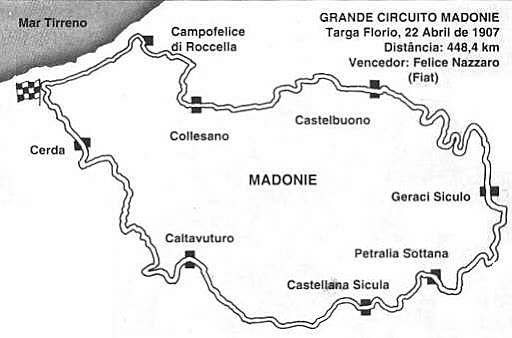

Except they did, of course, in the Targa Florio. This extraordinary race, begun by Vincenzo Florio in 1906 – 21 years before the first Mille Miglia – endured as a heat of the world sports car championship until as late as 1973, though the Sicilians persevered with the race until 1977.

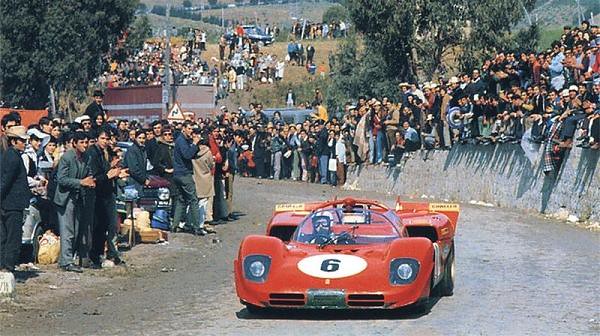

On roads more suited to rallying, brave men (and just a very few women) came to race their powerful and exotic P4 Ferraris, 908 Porsches and T33 Alfas – cars designed for the outright speed of Le Mans and Spa – and somehow survived the almost unrelenting twists and turns of roads that began as paths for donkeys thousands of years ago.

They raced through a seemingly endless sequence of abrupt corners, weaving bends and zig-zag hairpins. They flashed past olive groves, vineyards, market gardens and clumps of fig and Australian eucalyptus trees, in the shadow of beautifully rugged mountains that reach almost 2000 metres into the sky. They drove on roads creased and ravaged by seismic contortions, which corkscrewed the car while acting as a launch pad that could easily hurl any swiftly driven racer into a stone wall or guard rail.

There was but one moment of respite – the 4.3km Buonfornello straight that runs parallel to the coast between Campofelice and the Cerda station, just before the pits and the start-finish line. Here the drivers could relax, albeit at close to 350km/h.

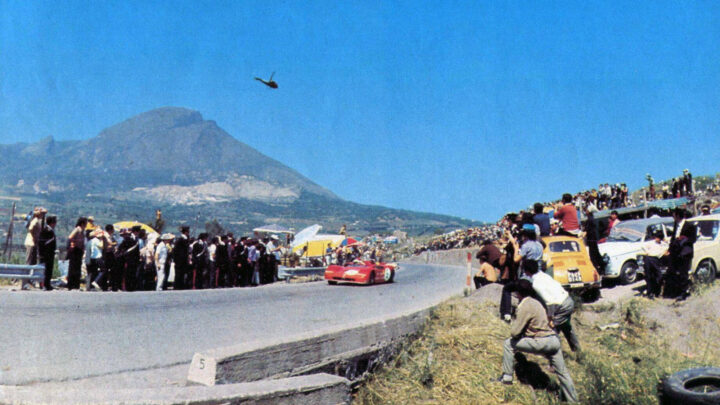

In two places the circuit opens out into a roller coaster, descending one side of the steep valley and up the other, offering a panoramic view of 10km of the circuit to the hundreds of thousands of spectators who lined the course. They would sit on the hillside by a campfire, eating olives and home-made salami, waiting for the first car to arrive. Nino swears the drivers could smell the meat cooking, could hear the shouting above the engines. I doubt there has even been a finer, more enjoyable place to watch a motor race.

In two places the circuit opens out into a roller coaster, descending one side of the steep valley and up the other, offering a panoramic view of 10km of the circuit to the hundreds of thousands of spectators who lined the course. They would sit on the hillside by a campfire, eating olives and home-made salami, waiting for the first car to arrive. Nino swears the drivers could smell the meat cooking, could hear the shouting above the engines. I doubt there has even been a finer, more enjoyable place to watch a motor race.

Nino Vaccarella, hero of Sicily was then headmaster of a private school his father founded in 1936. When he raced, he was a teacher, a mild mannered, humble, and charming man who made the Targa his own. He won it three times (1965 – Ferrari 275 P2, 1971 – Alfa Romeo T33, 1975 – Alfa Romeo T33 TT12), from an amazing 16 starts, the first in 1957 in a Lancia B20 GT, just two years after he began racing in hillclimbs in his father’s Fiat 1100.

Vaccarella learned the Targa roads as a young boy, travelling to visit his grandparents who lived in Petralia, high in the hills just beyond the circuit.

“My father would tell me, this is the Targa Florio,” he said, explaining the intimate knowledge that would mean he was 40 seconds a lap faster than Ludovico Scarfiotti in the 330 P3 Ferrari they shared many years later.

“Then, when I was 16, I came to see the race with friends. That year an Italian driver, Franco Cortese, won in a Fraser Nash. I remember, it was green.”

Though Jaguar and Aston Martin tried, the 1951 victory was the only one by a British car in all the 61 Targa Florios. Alfa Romeo and Ferrari both won eight times, Porsche eleven, Bugatti five, Mercedes and Lancia four.

On that day, 29-years ago, I set off in an Alfa Romeo SZ (the so ugly it’s fabulous, Zagato-built, coupe based on the rear drive V6 75) with Nino Vaccarella to do a lap of the Piccolo Madonie circuit and bathe in the mystique of a unique and wonderful motor race.

To find the Targa Florio you drive 65km east from Palermo to Imera and join the SS 120 towards Cerda. After turning inland from the sea, the road runs beside a railway line for a mile or so, then forks and beings a gentle climb to the old pits. Even these are on a corner, as if to set the atmosphere for the whole event. Three generation of buildings line either side of the road. The new section is still used for historic Targa meetings, but the faded paint and old posters of the control tower tell of another era. The road splits here, following the separation of the pitlane and the racetrack.

To find the Targa Florio you drive 65km east from Palermo to Imera and join the SS 120 towards Cerda. After turning inland from the sea, the road runs beside a railway line for a mile or so, then forks and beings a gentle climb to the old pits. Even these are on a corner, as if to set the atmosphere for the whole event. Three generation of buildings line either side of the road. The new section is still used for historic Targa meetings, but the faded paint and old posters of the control tower tell of another era. The road splits here, following the separation of the pitlane and the racetrack.

There is nothing more eerie than the calm of ancient motor racing pits. In the Floriopoli pits the ghosts of Nuvolari, Nazzaro, Varzi, Taruffi and Musso linger in the cool air. Fangio, Moss. Brooks, Bonnier, Gendebien, Attwood, Mairesse and Hawkins all stalked this ground.

Vaccarella becomes wistful. “The Targa Florio was a beautiful page in the history of the Sicilian people, it brings back so many memories. Everyone knew everyone, even if they were your opponents, they were friends.”

From the pits the road winds up to Cerda, a serpentine track impeded by a town. The long main street between the houses is narrow, but still the fastest cars reached 250km/h. The road meets the horizon at Granza where it plunges down into the valley from Sciafani Bagni to Scillato. There’s a small monument to Count Masetti, twice Targa winner, who rolled his Delage here in 1926 and was killed. Some insensitive road worker has painted the memorial in white, hiding the inscription.

“So stupid, I don’t understand,’ says Nino. “I shall tell them it must be fixed.”

A little further on Nino shows us the stone wall near Caltavuluro where Brian Redman crashed his Porsche in 1971, the car catching fire and inflicting severe second degree burns to his face, neck, and hands.

Beyond Scillato, the countryside is barren, stark; towns cling to the cliff-faces, the road bucking and weaving across the mountain to Collesane – where Vaccarella is an honorary citizen – and a famous corner.

In 1967, Enzo Ferraro sent a 4-litre, 450-bhp P4 to Sicily for Nino in the belief that massive power would defeat the nimble Porsches. Nino was easily quickest in practice and half a million people lined the route in expectation of a Sicilian victory. The magnificent Ferrari led by 90 seconds on the second lap. Down into Collesano he raced, through the corridor of people, waving to his fans. The corner is sharp, a 120degree left hander, and slow because the road is so narrow.

Did the wave mean lost concentration? Did the car catch the marbles? Whatever, Nino lost it and bounced both front wheels against the wall, wrecking the rims and handing the race to Porsche. The euphoric crowd was now silent.

Nino explained, “I arrived a bit too quickly, the brake pedal went down, the car skidded, and I hit the curb. Ferrari told me later, ‘next time don’t wave to the crowd’” The following year, Vaccarella arrived at the corner to find ‘Attento Nino’ painted on the wall approaching the turn. We found the Collesano corner almost unchanged since that disappointing day 25-years earlier. The Attento Nino sign had faded was still readable.

In 1992 Nino Arcara still operated his garage, on the outside of the corner, below his home. It was Arcara who collected and stored the Ferrari and looked after Nino until the race was over.

Did he hear our SZ or did some second sense tell him Vaccarella had arrived? No sooner had we stopped than Arcara rushed out, shaking hands with our party and greeting Nino like a hero. Nothing was too much trouble: we saw his racing Moto Guzzi bikes, his 911 and his old Targa photographs and left with armfuls of the local oranges and lemons.

The fruit reminded Vaccarella of his visit to Ferrari in 1962. There he was, a Sicilian school teacher who’d performed so well for the privateer Scuderia Serenissma team, he was offered a works drive for the famous team – the dream of every Italian who ever held a steering wheel. What, Nino wondered, could he possibly give Enzo Ferrari to express his elation.

What better than a box of ripe Sicilian mandarins?”

“I nursed them on the plane and in the car from Bologna and immediately gave them to the Commendatore,” remembered Vaccarella. “He seemed delighted and sent them straight over to the Cavalino restaurant.”

“They were there when we went for lunch. The Commendatore put his arm around me why trying one and said, ‘So many good things come from Sicily.’” That day Vaccarella signed with Ferrari.

By now, word has spread and other Vaccarella fans have gathered, excited at seeing their hero again.

“When the Sicilians realised there was a fellow Sicilian capable of winning, they took him to their hearts,” Nino explained simply. “Up to then they had always seen foreigners or Italians starring and winning. I felt an enormous warmth, but also an extra responsibility.”

All week long we’d been parking the Alfa in secure garages. Nino wanted us to try his favourite cannoli and told us to leave the car in the town piazza. Photographer Stan Papior, terrified all his equipment would disappear, wanted to say with the SZ.

“Leave it here.” Nino said. “Leave the keys, it is safe.”

So we did and it was.

From Collesano the road gradually begins to open out, the corners beginning to string together before Campolelice and the long run beside the sea.

“Le Mans was not tiring (Nino won the 24-hour race in 1964 in a 275 P Ferrari), not compared with the Targa,” he shakes his arms, wobbles his head, recreating the brrrummmbrrrumm noises to demonstrate the constant gear changes and body movements. “You were always turning, so when you came to Buonfornello, you’d slump down into the seat (he sighs and slides his backside forward) and relax your breath,” At 350km/h.

In 1971 Ferrari ignored the Targa and Nino drove an Alfa Romeo T33/3, hoping to break the Porsche run of five consecutive wins. The race was a pitched battle between Vic Elford’s Porsche 908/3 and Vaccarella. Elford set the fastest lap, and the lead swapped back and forward before Gerard Larrouse, Elford’s co-driver, had two flats and had to limp 30km kilometres back to the pits, causing suspension damage. The local hero had broken Porsche’s domination.

The signs painted on walls, houses and the road, are faded now but you can still make out ‘Viva Nino’ and ‘Forza Nino’, expressing the hunger for success of one of their own from a proud and generous people.

To put the Targa into perspective you should know that the short circuit was 45-miles long, where once the race had been one 1077km lap of the entire island. There were three Madonie circuits: the 148km Grande, 108km Medio and the 72km Piccolo. In the later years the race was over 11 laps – 792km – and Helmut Marko Alfa T33 left the lap record at 128km/h in 1972, taking little more than 33minutes 41 seconds to cover the entire distance. The last world championship event was 1973, but after an Osella went into the crowd in 1977, killing four people, it was the end.

To put the Targa into perspective you should know that the short circuit was 45-miles long, where once the race had been one 1077km lap of the entire island. There were three Madonie circuits: the 148km Grande, 108km Medio and the 72km Piccolo. In the later years the race was over 11 laps – 792km – and Helmut Marko Alfa T33 left the lap record at 128km/h in 1972, taking little more than 33minutes 41 seconds to cover the entire distance. The last world championship event was 1973, but after an Osella went into the crowd in 1977, killing four people, it was the end.

Vaccarella wanted to be remembered for more than just the Targa Florio. After all, he won at Le Mans, Spa and Daytona in sports car and drove a single F1 race for Ferrari – Monza in 1965 when the engine blew up – as well as nine F1 races for Serinissama. That’s not going to happen so idolised is Nino by his fellow Sicilians, that even he realised that was impossible.

The last of the great open road races, a spiritual link with the very dawn of motor racing, has been dead for decades. Yet, it’s still possible to drive on the same fantastic roads, through the unchanging villages, to stop at the old pits, to relive something of the challenge of the Targa Florio.

Yes, I smiled, and pulled out the old photographs of Nino, taken that magic day 29-years ago, and remembered.