by Peter Robinson

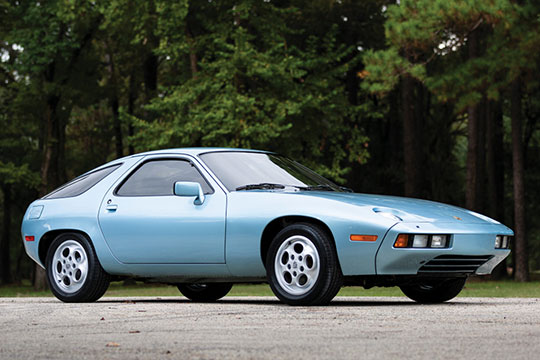

Even now, 27-years after the 928’s death, Zuffenhausen doesn’t like to be reminded that its front engine V8 started life as a replacement for the 911. The 928 arrived in 1977 with a price tag 38 percent higher than the 911, yet Porsche still believed it could replace the classic rear-engine model. However, it quickly became obvious that traditional Porsche buyers didn’t see the 928 as a successor: it was too big to be a proper uncompromising sports car, and so they continued to buy the enduring 911. Porsche tried turning the 928 into a proper grand tourer, but it was too small to be a serious four-seater and too harsh and noisy riding to be truly comfortable.

Eventually, despite the combination of poor packaging and a high price that meant the 928 only took about 10 percent of Porsche’s business, the 928 was thoroughly and carefully developed into something quite unique. For those who loved its virtues of soaringly effortless performance, remarkable high-speed handling and the integrity of its build quality, even the heaviness of its controls, the 928 was close to perfection.

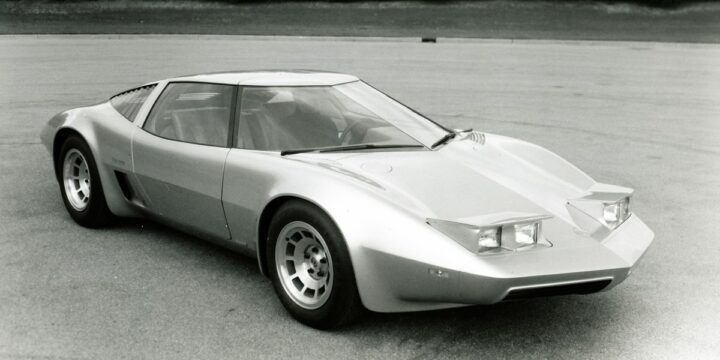

How the 928 came into existence is a fascinating tale. How many of you realise there is a clear design link between GM’s stillborn Wankel XP-987 two and the Four Rotor (later renamed Aerovette) Chevrolet Corvette and the 928?

One of the fundamental factors in the creation of the 928 occurred during a chance meeting in Germany between Anatole ‘Tony’ Lapin and the Porsche family. Lapine, an American designer from GM’s Detroit studios where he worked on Corvettes, was on assignment to Opel in Germany. It was he who suggested the senior Porsche people should visit Opel’s new studios.

It was 1968 and Chuck Jordan, the American design chief at Opel, was greatly impressed that a group of old-world Porsche executives, including Ferdinand Piech, FA ‘Butzi’ Porsche and Ferry Porsche, would be interested in exploring Opel’s modern Russelsheim studios.

“We thought their visit would be good for motivation,” Jordan told me decades later.

“We couldn’t believe it when they turned up in a huge, air-conditioned Pontiac station wagon. We expected them to turn up at the meeting point just off the autobahn with their 911s’ brakes smoking.

“We had dinner in an old castle before we showed them through the studio. It was a great honour for us.”

Lapine, articulate and multilingual, must have impressed the family, for within weeks an approach came to join Porsche. In 1969, Lapine and, over the next couple of years, four colleagues left Opel and joined Porsche. Jordan was not impressed.

“It was not that wonderful for us,” he said. “But I could see it was a great opportunity for Tony.”

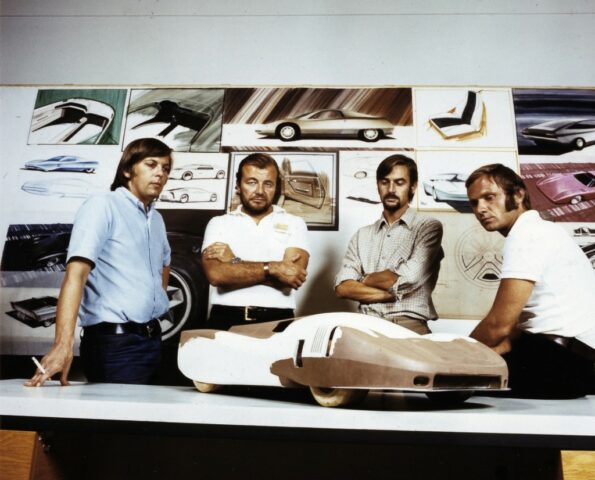

Those men – designers Dick Soderburg and Wolfgang Mobius, modeller Peter Reisinger and engineer Jurgen Mayer, plus Lapine – were to form the core of the team that designed both the 928 and (with much input from Harm Lagaay) the 924, though they worked in two separate studios so one could not influence the other.

Other events were also shaping the future. For Porsche, 1971 was a traumatic year. Management and ownership were separated when Ferry Porsche and his sister Louisa Piech decided all the many third generation members of the feuding Porsche and Piech families employed by the company – including Ferdinand Piech and Butzi Porsche – should step aside from the business when it became a public company. Ernst Fuhrmann, an engineer who’d earlier worked for Porsche, returned to become Zuffenhausen’s leader.

At the very last minute, new VW boss Rudolf Leiding cancelled the mid-engine EA266 engineered and designed by Porsche, deeming it too much of a risk to be a Beetle successor. It was a savage blow to Porsche which was counting, not only the royalties from the EA 266, but had begun to design a true replacement to the 356 and the 914 around its mid-mounted flat four engine.

Fuhrmann immediately initiated further development of the already eight-year-old 911 and began seriously looking at a successor. Today, it seems almost inconceivable that Porsche should have committed itself to a replacement for the 911, but in 1971 it appeared inevitable. As far back as 1969, Zuffenhausen estimated the 911 could only survive until 1974.

The end was in sight for the Beetle, at least in Europe, and front-wheel drive seemed the future for small cars, mid-engines for sports cars. An air-cooled engine hanging out behind the rear wheels was considered archaic by many at Porsche, who could see the coming safety, emissions and noise requirements would be difficult, if not impossible, to meet with the 911.

Porsche, under R&D boss Helmut Bott, had already begun researching various alternative technical layouts. It seemed the 911’s engine was at the end of its potential, although one early design proposal shows a 928-like design with the flat-six mounted behind the rear axle line. Ferdinand Piech even suggested a new V8 to be positioned in the rear of a similar design.

Finally, on October 21, 1971, Fuhrmann decided the new car should have a front engine, probably a V8, and rear-mounted gearbox to give near perfect weight distribution. Porsche knew Alfa Romeo was planning a similar layout for the forthcoming Alfetta and Alfa was seen as a serious rival. Thus the 928 would be that rarity among cars, a new model owing nothing to those that had gone before.

This mirrored the technical layout of the four-cylinder 924 sports car Porsche was developing for VW. Creating the two models in parallel made sense. Initially, the 928’s 90deg V8 was to be five-litres with one camshaft per bank with the proviso that a spin-off four-cylinder engine – one bank of the V8 – would share as many components as possible and be used as a starting point for a possible future smaller Porsche.

Eventually, in view of the energy crisis, management decided to limit the engine capacity to 4.5-litres. Of course, when VW killed its plan for what became the 924 in 1975, and Porsche bought the rights to the model, the half-bent eight was later (and thankfully) slotted in as a replacement for the 924’s coarse 2-litre VW van engine, to create the vastly improved 944.

Under the leadership of Lapine, Mobius (with help from Jiri Kuhhnert), designed the 928 with Reisinger providing invaluable surface crafting as chief modeller. The package called for a car just a little longer in wheelbase and length and slightly wider, than the 911. A Mercedes-Benz three-speed automatic transmission would be optional and, like the five-speed manual, use a transaxle.

Porsche wanted a two-plus-two, rather like the 911. However, as the engineers finalised the packaging, they realised the sheer bulk of the automatic was going to add considerable width to the body, if the two small rear seats were retained in their positions between the transmission tunnel and the rear wheels. It was this compromise that forced the 928’s width to blow out well beyond Mobius’ original design proposals and would eventually make it a massive 186mm (7.3in) wider than the 911.

That led some Porsche executives to ask if it should be enlarged even further to become a true four-seater and for the development of a (stillborn) station wagon/estate version, on the same wheelbase, with its extended roofline giving the necessary head room. The four-seater debate was spurred on after the energy crisis of 1973 when the entire 928 project was questioned. Alternatives, including, astonishingly, a front drive 911, a reskinned 911 and a flat-six 928 were considered before the board chose, on 15 November 1974, to go with the original 928.

Mobius’ major task was then to disguise the 928’s vast width. This led to Europe’s first ‘soft’ production car, and a hugely influential design that was copied and recopied for almost two decades. It was the polar opposite of the flat, hard designs Giorgetto Giugiaro was attempting at the time.

“I think it looks better today than it did 18 years ago,” Mobius told me in late 1995. “It may have been too far out, and it wasn’t easy to understand initially.”

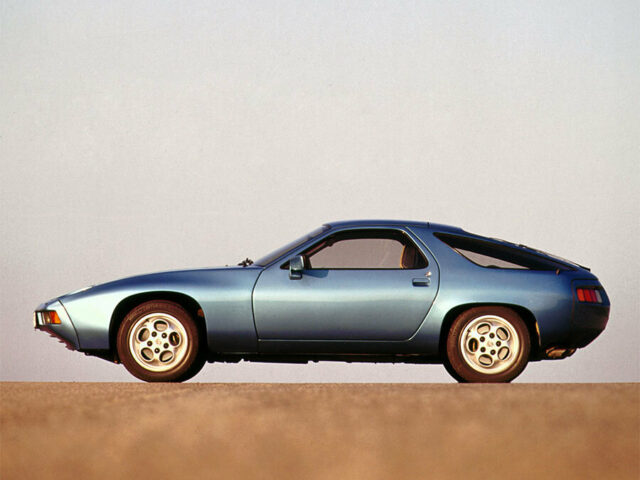

The 928 still looks smaller than it really is. Approach the car from three-quarters front or rear and, because of the body’s extreme taper at each end, there appears to be very little overhang. In contrast, look at the car in profile and the long overhangs are exaggerated. The bumpers were so beautifully integrated into the design that, back in 1977 when the 928 first appeared at the Geneva show, people said it had no bumpers at all. They proved a major technological feat: Porsche developed the 928’s styling using both conventional bumpers and the new integrated units simultaneously on the one full-size clay.

Matching the colour of the steel body with the polyurethane bumpers proved difficult because, initially, different paints were used for the different materials. Well into production the problem was solved by painting the two parts together. Mobius spent two weeks in the US with Ulrich Bez, then a Porsche engineer and later head of R&D (and later still CEO of Aston Martin) in 1972 working with Union Carbide on a solution.

Mobius also wanted to hide the position of the engine by reducing the size of the front air intakes. People thought of Porsches as rear engined and this mild deception seemed important at the time. Many of the design themes of the 911 were retained: the tapering shape of the long thin C-pillars, when seen from directly behind, almost duplicate the 911’s rear window; the sloping nose and the desire to retain round headlights and make them visible even when flush with the body.

The lean of the B-pillar meant the upper edge of the door would be soft so that it didn’t form a sharp edge that might catch occupants in the chest when exiting the car. They tried fixed headlights on the long fenders, but it just didn’t work according to Reisinger, who believed the result looked awkward.

“We were struggling to get the surface development right,” Reisinger explained, “We were playing with reflections to make sure there were highlights on the front fenders and to get the shapes working together.”

At one stage the engineers returned from prototype testing in Africa and insisted the ride height be raised by 50mm to give more ground clearance.

“I couldn’t believe the change,” Mobius said, “It really should have been 50mm lower.”

If the exterior set new trends, so did Hans Brauns’ brilliant interior: it was the first to merge the doors and the dashboard into one, integrated design. Brauns worked with Dawson Sellars, a Scottish designer who came to Porsche from Ford in 1971 to work on the 928’s interior.

“Brauns did the bit in front of the driver,” according to Sellars who went on to design street cleaners and forklift trucks from his office in Kirkcudbright. “I was responsible for the rest. There were no carry-over bits at all and lots of space for style. Right from our first sketches we wanted to blend the dashboard into the doors.”

The steering wheel moved up and down in concert with the instrument panel, the seats were embraced between the central tunnel and the doors sills, turning the disadvantage of the bulky tunnel required to house the automatic transmission into a design feature incorporating the dash console.

When Lapine started at Porsche, the design studio was in a tiny workshop behind the head office in Zuffenhausen and he wondered what he’d done. By 1975 a virtual miniature of the Opel studios had been created in Weissach.

Production of the 928 finally came to a halt at the end of the 1995 model year after a run of almost 61,000 cars, the last being built to order as the parts bin emptied. Today 928 values have begun to rise, but it is almost totally overshadowed by the 911.

“For 15 years I was a 911 freak,” Reisinger admitted. “I couldn’t imagine changing to a bigger car, but I thought I should try the 928. I loved it more every day. Maybe it’s because of my age. They’re both Porsches but their character is completely different.”

And the connection with the Corvette? Just look at the shared design elements between the 928 and the two and four rotor Corvette concept cars.