For five months, Hruska worked on defining the concept. All the market research told him Alfa should build a small ‘people’s car’, with front wheel drive, that retained the Alfa character. He was pragmatic enough to know it needed to seat four adults in comfort and carry their holiday luggage. To endow the car with the necessary space, keep dimensions down, allow a low bonnet line and good aerodynamics and to provide the perfect balance for superior roadholding and handling, Hruska insisted it should have a boxer – horizontally-opposed – engine that could later be developed for higher performance.

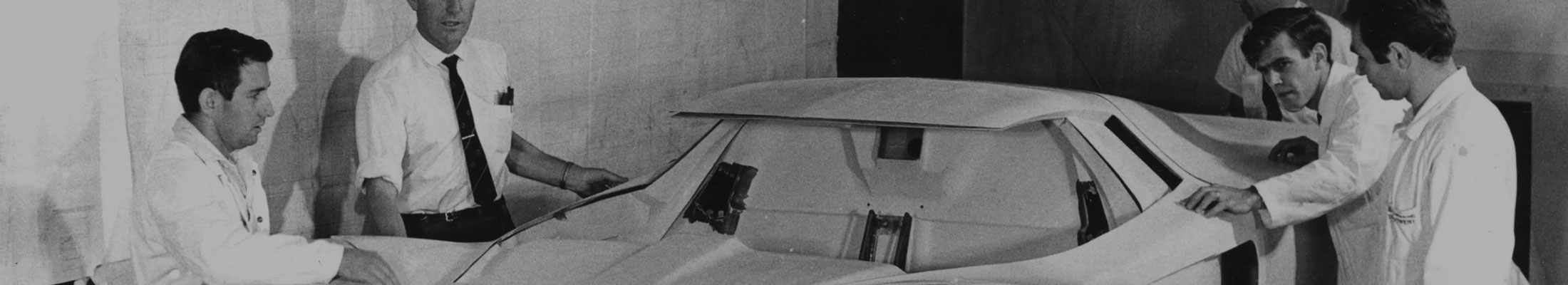

These explicit objectives were given to Giorgetto Giugiaro, whom Hruska decided should design his car. Giugiaro’s new Italdesign, set up with engineer Aldo Mantovani, was given the task of developing and engineering the project and even the building of prototypes and the tooling. Giugiaro and Hruska had worked together when Rudi was still at Fiat and Giugiaro was at Bertone, in developing the beautiful 1965 Fiat 850 Spider and clearly respected each other’s talents. Giugiaro had just established Italdesign and Alfa Romeo (in reality Hruska) was his first major client.

But the Alfasud’s intrinsic qualities never had a chance.