by Hugh King

HE PIONEERED AIR ROUTES FOR THE WORLD, AND WROTE EIGHT BOOKS ABOUT HIS WORK

An important participant in building the Aviation Heritage of Australia

Australians today may not recall much of Sir Patrick Gordon Taylor, one of the great and good adventurers of the twentieth century. He was responsible for many elements of safe air travel that we enjoy now. My own knowledge is meagre and second-hand, gained through a school connection and through owning and enjoying the eight substantial books that he wrote in the latter thirty years of his long life. Those eight books are now at the AMHF, they live on and are his memorial now.

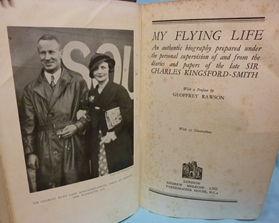

Sometimes known as ‘Bill’ or ‘P G’, Taylor was born in Mosman and died in 1966 in Honolulu, at the age of seventy. His life was remarkable for the extent and depth of his achievements in aviation, in warfare over the Western Front with the RFC in 1917-1918, then in dangerous pioneering work centred on establishing air services for Australians on both international and domestic routes, taking risks with Kingsford Smith and with Charles Ulm, and in 1939-1945 with the RAAF.

From his Mosman home Taylor was sent as a teenager 360 miles and 24 hours away by train to The Armidale School, on the New England tableland, which had been set up in the 1890s as a private boarding school for boys on the Rugby model, not a diocesan entity but ‘connected with’ the Church of England. Taylor was senior prefect in both 1914 and 1915.

Within a few months of leaving the school in 1916 Taylor was writing from England to his old teachers, as a school historian has recorded, that he had joined the Royal Flying Corps in August 1916 and enjoyed his flying training ‘and if I get on well I intend to take it up as my profession after the war’. He already had a lyrical touch – ‘At about three thousand feet I ran into clouds, at about four thousand I was above them. It was a magnificent sight – a blue sky above, and the sun shining on a bank of clouds below. The feeling is one of loneliness, but perfect security’. He told of ‘looping the loop’ and said that although the first time took courage, ‘after doing it once, one rather enjoys it’. Known in the officers’ mess as ‘Wallaby’ he joined 66 Squadron which was equipped with Sopwith Pup ‘scout’ or fast fighter aircraft, located in France behind the Western Front.

Taylor was successful in combat and after 40 missions was awarded the Military Cross for valour in July 1917. As a Captain at the age of 21, he was moved to other front line fighter squadrons where he fought with aces including Billy Bishop VC and James McCudden. He wrote an extensive and eloquent diary of his whole wartime flying experience. He was affected by the loss of his brother Ken in the war and by the task of killing (at which he had gained great expertise), and expressing clear distaste for war, he refused until near the end of his life to publish his war record. So his eighth and final biographical work, published posthumously in 1968 returns the narrative to the Great War and is titled ‘Sopwith Scout 7309’ – that ‘plane was his first and favourite weapon, his saviour in combat.

A personal note – I arrived as a junior boarder at The Armidale School 40 years later, in January 1956 at the age of twelve years. It was all-male, both as to staff and internees, still a remote self-sufficient world operated on the Rugby School model, and very ‘connected with’ the diocese of Armidale. War service by our Old Boys was kept front-and-centre with the Book of Honour in the daily Chapel. Our House Master was a decorated ex-RAAF veteran with a sad backstory. Our two rifle teams were NSW school champions with their Lee-Enfield .303 rifles beautifully cared for. There was in the school quadrangle a functioning field gun and occasionally a Daimler Staghound armoured car (the Commandant of the cadet corps, our science master was concurrently a Major in the 12/16th Hunter River Lancers, an Army Reserve unit derived from the 16th Light Horse). Even then, boys in the cadet corps underwent live firing practice, weekend bivouacs and specialist training with sniper rifles, bayonets, smoke grenades, Vickers water-cooled machine-guns and the Owen ‘personal weapon’.

In December 1951 the famous Old Boy, Captain Gordon Taylor, George Cross, MC had visited the school to inspect the cadets’ traditional ‘Passing Out’ parade and to deliver the eulogy and prizes to final year students. By my time we knew he had been knighted in 1954 and this fact kept the stories alive. In 1956 it was to be Sir William Slim attending this ceremony. This was our world then, and like Taylor in his time there just 40 years before, we knew no other.

At the end of the Great War Taylor was in ‘idle’ mode attempting to gain certainty, stability and some understanding of the direction in which the unfamiliar new world was moving. He did not write of this time although others have described it, notably Neville Shute Norway in Slide Rule (1954), Brogden’s History of Australian Aviation (1960) and others in standard historical work.

Soon Taylor was in England then in Sydney, working for De Havilland. In 1930, his contemporaries Kingsford Smith (who had won a Military Cross over the Western Front) and his partner Charles Ulm were forming a new airline and had Taylor in mind. The two war veterans Taylor and Smithy had talked business initially on return from the war in 1921 and then seriously in 1927 in Sydney, by which time both of them had established a reputation respectively in providing public (domestic) aviation services in Sydney, at the new Mascot airfield, with small start-up airlines.

Kingsford Smith and one Keith Anderson had set up Interstate Flying Services, with the aim of eventually pioneering mail and passenger services on the trans-Pacific route to America. Ulm had established Aviation Services Co. with six de-mobilised officers of the RFC and the Australian Flying Corps. Ulm had good administrative skills. Kingsford Smith was more unorthodox and a salesman as well as a natural pilot of difficult aircraft. He was also a writer and publicist. Ulm and Smithy shared memories and an intention to explore and expand into the primitive Australian aviation industry, and to support and favour their contemporary well-experienced adventuresome wartime flyers (there were a few available!) for crew and partners. For them Taylor was suitable in 1930 for employment as a safe pilot at senior levels.

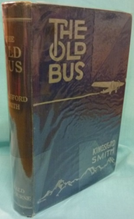

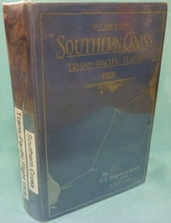

In 1928 Kingsford Smith and Ulm succeeded after many setbacks in securing funds from an American backer to buy, re-engine and equip, then to fly the big Fokker F.VII tri-motor which they re-named ‘Southern Cross’. This particular ‘plane had been owned and named The Detroiter by Sir Hubert Wilkins, the Australian pioneer Arctic explorer and was used (and crashed) in Alaska in 1926. The saga of the first long flight by the rebuilt ‘Old Bus’ piloted by Kingsford Smith and Ulm from Oakland, California to Australia in June 1928 is not pertinent here, except in that it provided the publicity, credibility and name-recognition (and some money) necessary for the next stage of the friends’ plan, which was the establishment of their new company – Australian National Airways Limited – on 12 December 1928.

The new airline known as ‘ANA’ was based at Mascot with small fleet of Avro 10s, a licence-built copy of the Fokker tri-motor aircraft including the Southern Cross. ANA had contracts to fly mail and passengers on routes between Brisbane, Sydney, Melbourne, Launceston and Hobart. It was an ambitious venture without any Government subsidy, but it made good money and built prestige during 1929-1930 often flying at full capacity. Taylor was recruited by Ulm as a captain in 1930 and this move began his first decade of pioneering adventure.

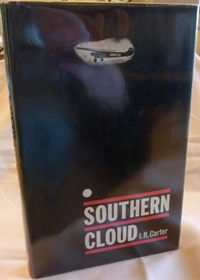

ANA struck misfortune when one of its Avro 10s, the Southern Cloud disappeared without trace in March 1931 over the Southern Alps of NSW while flying the Sydney-Melbourne route. All eight on board were lost. A lengthy search attracted great attention to ANA and the dangers inherent in aviation (the wreckage was discovered only in 1958 and a memorial cairn stands on the north road into Cooma). This was not only a highly publicised tragedy with local human dimensions, but also the start of a financial tailspin for ANA and its two founders, Kingsford Smith and Ulm. The costly search and the drop-off in business added to the burden of personal loss.

This led to the company ceasing operations in June 1931. But it did not cause Ulm to abandon his plans for an overseas service. Taylor writes in ‘VH UXX’ (1937) that ‘those of us who had been with ANA and who were able to do it, now formed into a voluntary body to pursue the overseas mail plan … we had some sort of an idea that the successful efforts of the airmen and administration that had pioneered the mail route would be taken seriously into account by the Australian Government’.

Until 1931 the air mail service from England (that is to say, the outside world) did not extend beyond India. Ulm and Kingsford Smith worked on the idea of running an Australian air service up to Calcutta, to complete the ‘Empire’ route between London and Sydney. Imperial Airways Limited, operating the London-Calcutta route had the same idea and on 4 April 1931 one of its machines left London with mails for Australia. That machine was wrecked at Koepang on 19 April and so, under charter to Imperial Airways, Kingsford Smith flew the Southern Cross to take the mails and deliver them to Sydney, then take London-bound mails from Sydney to Burma. The Southern Cross became an integral part of the first official England-Australia air mails, and it was a profitable venture just as predicted by Ulm and Kingsford Smith.

Funding was hard but more operations were planned, and a pioneering run from Australia to England with a heavy load of Christmas mails left Australia in November 1931 in ANA’s Southern Sun (like Southern Cross, an Avro 10 tri-motor monoplane). Southern Sun was wrecked en route and a replacement ANA Avro 10 took the mails to London, returning late in January with mails to Sydney. This brave venture was a further loss to Kingsford Smith and Ulm, compounding the public image troubles arising from the earlier loss of Southern Cloud and sealing the fate of ANA.

Charles Ulm’s stayed with the objective to start an England-Australia service to be subsidised by the Australian Government. He pushed for the calling of tenders, assisting the Government by providing all ANA’s data on developmental work done on the routes.

The Government acted eventually in 1933 announcing that tenders would close on 31 January 1934, to be accepted only from ‘Australian companies’ as the service was to be subsidised. Imperial Airways formed a liaison with QANTAS to enable a bid on the stated terms, and it was major competition for Ulm, the pioneer on the route.

For Ulm and his team, now including Taylor, publicity became a key issue for the bid being made by the Australian enterprise which had pioneered the mail route. The most valuable publicity avenues in Australia were open to Imperial Airways and to Hudson Fysh at QANTAS, but were closed to Ulm. Characteristically, the team decided to do something which would create ‘news’ while also showing up the opposition – around the world. Taylor tells the story in his ‘VH UXX’ (1937).

Ulm and a few loyal supporters pooled resources and bought the Southern Moon from the liquidators of ANA. This was an Avro 10 built by Avro in England, having a slightly shorter wing-span and three Armstrong Siddeley Lynx engines, one of the most successful commercial aircraft in the ANA fleet, having been used on the Sydney-Brisbane run flown by Taylor. This was a good if obsolete unit with great structural strength and the unique Fokker light, thick wing able to be evolved into a machine weighing 6,000 pounds and capable of lifting an overload of fuel (16,000 pounds in lieu of the usual 10,225 pounds) for long ocean stretches extending to 3,200 miles.

For the engineering work the team engaged the displaced ANA engineers and a lead designer, the great Queenslander Wing-Commander (later Sir) Lawrence Wackett, an ace in the pack. The ‘plane was re-engineered, the wingspan extended, the engines and landing gear replaced. The registration number was VH-UXX and the name became ‘Faith in Australia’ as a subtle hint to the Government in dealing with the contested tender.

Faith in Australia first flew in its new colours on 1 June 1933, completed testing and then lifted off from RAAF Richmond for London via Derby, W.A. on 21 June crewed by Ulm, Taylor and ‘Scotty’ Allan. They landed at Heston near London 17 days later. ‘Round the World’ was the object.

The onward flight to Sydney over the USA started poorly, with the ‘plane damaged by tides at the chosen departure point at Portmarnock Beach in Ireland, but such was the goodwill and publicity that funding was put up immediately by Lord Wakefield, the British petroleum products ‘king’. The damage was repaired, but persistent bad weather stopped plans for the round-the-world flight. The London-Sydney record was tempting, it had been set by CWA Scott at 8 days, 20 hours but bettered by Kingsford Smith in Miss Southern Cross on 11 October 1933. Ulm decided on good commercial grounds fly to Sydney in competition with Kingsford Smith, to demonstrate the possibilities of commercial air services operated by Australians.

So Faith in Australia with Ulm, Taylor and Allan left Feltham near London on 13 October and landed at Derby, W.A. in a new record time of 6 days, 18 hours. They flew on to Sydney arriving on 28 October. The Aero Clubs’ welcoming party flying over Parramatta included Southern Cross and Kingsford Smith in Miss Southern Cross.

But this booster was not sufficient to win the Government contract for Ulm over the Imperial Airways/QANTAS combine.

Taylor joined Kingsford Smith and in the years 1934-1935 undertook the two air voyages which have won him honours and defined his reputation. These are described in three of his books – Pacific Flight (1935), Call to the Winds (1939) and The Sky Beyond (1963).

The Australian Dictionary of Biography describes the first flight in too-brief terms – “Disappointed at missing the Victorian Centenary Air Race, ‘Smithy’ and Taylor completed the first Australia-United States of America flight, via Suva and Hawaii (21 October-4 November 1934) in the Lockheed Altair Lady Southern Cross”.

Taylor’s book about the pioneering flight is itself too brief, at 260 pages – the voyage by the two men was epic and important for us all, helping greatly to reduce Australia’s isolation just five years before the commencement of our remote nation’s greatest test yet, at the hands of the Japanese.

Taylor understood this motive well, as spelled out in Pacific Flight – “It was clearly not done with any deep-rooted idea of the great benefit it would bestow on humanity .. but … it was the second crossing of the Pacific Ocean in an aeroplane, and therefore the second step in showing how it could be done … the second lesson towards the cultivation of the idea of an air service up the Pacific from Australia – the second lesson in the creation of confidence and towards the defeat of natural human opposition to something new”.

This flight was in fact the reverse of that by Kingsford Smith and Ulm in the larger Southern Cross in 1928 from Oakland to Brisbane – that ‘first step’ six years earlier had earned a knighthood for Kingsford Smith but did not convince governments or commercial interests of the necessity for covering the route. Now Kingsford Smith and Taylor with the superb American long-range fast two-place Altair, with a single American engine, using American facilities at Hawaii at the mid-point, drew important attention to the safety and necessity attaching to this route linking the two continents. The Altair having arrived in Sydney by sea on the SS Monterey, it was taken first to Anderson Park, Neutral Bay. It flew to Mascot then on to Brisbane, where the trans-Pacific Flight commenced.

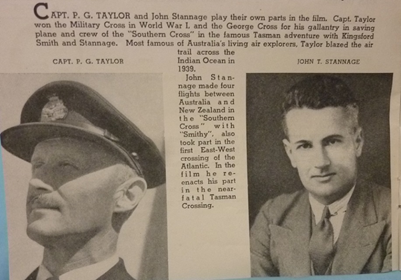

The second epochal flight is usefully summarised in the ADB in less brief terms – “On 15 May 1935 Taylor was Kingsford Smith’s navigator in Southern Cross for the King George V Jubilee airmail flight (Australia-New Zealand). After flying for six hours the heavily-laden aircraft had almost reached half-way when part of the centre engine’s exhaust manifold broke off and severely damaged the starboard propeller. ‘Smithy’ closed down the vibrating starboard engine, applied full power to the other two, turned back to Australia and jettisoned the cargo. The oil pressure in the port engine began to fall alarmingly. The flight appeared doomed. Taylor reacted heroically. Climbing out of the fuselage, he edged his way against the strong slipstream along the engine connecting strut and collected oil from the disabled starboard engine in the casing of a thermos flask. He then transferred it to the port engine. With assistance from the wireless operator, John Stannage he carried out this procedure six times before the aircraft landed safely at Mascot some nine hours later. For his resourcefulness and courage, Taylor was awarded the Empire Gallantry Medal (EGM) gazetted on 9 July 1937; it was superseded by the George Cross (instituted in May 1941). Taylor portrayed his exploit personally in the 1946 film Smithy directed by Ken G Hall”.

The Sydney newspapers then were published in several editions each day including Saturdays, and such was the public interest in Kingsford Smith and the Jubilee Mail flight that there were frequent updates on the status of the flight until the damaged ‘plane returned to Mascot on just two engines.

Taylor’s own comments about Jubilee Mail incident in Call of the Winds and in The Sky Beyond are blunt and sanguine. He makes the obvious point that to confront the danger as he did, was far preferable to the only alternative of failure of a second engine followed immediately by three deaths at sea. He is much more reflective and troubled about the deaths of Charles Ulm (1934) and Kingsford Smith (1935), both lost over the sea without trace while on record-breaker flights. In his log-book for the flight the entry is: “Oil Incident. 6 hours out. 9 hours back”.

Writing in 1963 about ‘the way ahead’ in The Sky Beyond Taylor speaks of his sense of ‘anticlimax’ and depression following the long fruitless search for Kingsford Smith. He bought ‘one of the most responsive and beautiful machines … a slim-bodied Percival Gull with a Gypsy Six engine … a dream aeroplane… very like the Spitfire of later years’. With this and a succession of similar small aircraft Taylor went on alone, operating a private charter service until war intervened. Based at Mascot he carried urgent photo deliveries overnight for the big daily newspapers between the capital cities – the Melbourne Cup, the Test matches, the Darwin cyclone in 1937. He participated in air search operations and medical evacuation operations.

Taylor’s personal life settled a little, as he divorced his first wife and married again in 1938. In June 1939 he pursued a further pioneering dream, looking west over the Indian Ocean to establish a direct air connection between Australia and Africa. No-one of influence believed this connection to be feasible, the facilities at Christmas Island, Cocos, the Maldives, the Seychelles and Diego Garcia were non-existent. He could find neither backers nor Government support.

At his own expense he went to America where he identified and chartered an early Consolidated Model 28 Catalina two-engine long-range flying boat named Guba owned by an explorer, Richard Archbold and located then in New Guinea. In talks with the Australian Treasurer R G Casey (later Lord Casey and a member of the British War Cabinet under Churchill) Taylor communicated some understanding of the national importance of his intended pioneering flight. The exploratory flight commenced on 4 June 1939 and the story was told by Taylor in some detail in The Sky Beyond in 1963 where again he is blunt in his comments – ‘Someone had to do it, in the national interest, but I might have been the only one to know that’.

The Governor-General Lord Gowrie VC telegraphed congratulations to Taylor on 25 June 1939 after his arrival in Mombasa on the east coast of Kenya – ‘Your courage and skill has added a chapter to history and opens up a line of imperial communications hitherto considered impossible’. Taylor passed his confidential report on the flight to the Prime Minister the day before war was declared on 3 September 1939. The report was immediately used in the selection of bases needed in the Indian Ocean by the Royal Navy, the RAF and later by the RAAF and the USAAF for operations against German and Japanese raiders. When the England-Australia air route was sealed off by the Japanese occupation of the whole area between India and Australia, air communication was maintained with London by QANTAS Catalina aircraft operating between Nedlands and Koggala Lake with an extension to Karachi – the ‘Double Sunrise Service’ or ‘Indian Ocean Service’.

War came, and Taylor pondered withdrawing entirely from flying for the duration, feeling strongly that he had ‘done his bit’ in 1917/18 and could not deal with the killing fields again at his age of 43. He wrote – ‘The thought of surrendering my personal freedom of action to the whims of the war machine really alarmed and horrified me’. He considered a life as a grazier, but after Pearl Harbour and the fall of Singapore he thought again. Being familiar with the strong long-legged Catalina for duty over water, he was recruited to fly a secret operation by Catalina for the Dutch West Indies Governor, then was asked by the RAAF to ferry Cats from the USA to Australia. He was a participant in the ferry flight of the first Catalina delivered to Australia for the RAAF. The story is told by Sir Hudson Fysh in QANTAS at War (1968).

From early 1942 Taylor was a civilian captain attached to No 45 Atlantic Transport Group of the RAF based in Montreal which was responsible for ferrying aircraft built in the USA across the Atlantic under Lend-Lease. He was commissioned as a Captain in the RAAF. More pioneering work followed.

In his book Forgotten Island (1948) Taylor relates how, in September 1944 he prevailed upon the RAF and the Under-Secretary of State for Air, Harold Balfour to permit him to work up another long-distance pioneering route with a RAF Catalina. This proposed route would be from England via the Pacific Ocean to Sydney over Montreal, Bermuda, Acapulco, Clipperton Island (the ‘forgotten island’ of the book) to Tahiti, Suva and Auckland thence to Sydney. It has to be mentioned that Balfour had been a fighter pilot and one of Taylor’s instructors in the RFC at Upavon on Salisbury Plain in 1916!

A suitable RAF Catalina No JX275 was located in Bermuda, and the flight would commence from there. A crew of three serving Australians and a New Zealander was allocated under the command of Taylor – second pilot, navigator, radio operator and flight engineer. The name Frigate Bird was chosen, high-capacity fuel tanks fitted and on 25 September 1944 the expedition began. All objectives were achieved and Frigate Bird set down in Sydney Harbour on 15 October. The new route was proven, and bases (including Clipperton Island) had been identified as suitable for staging points.

Next it was Sydney to Valparaiso [Chile] in March 1951, again by Catalina, again a pioneering flight. This was the first time across the South Pacific Ocean, to prove the prospect of a direct Australia-Chile link. Taylor wrote his full personal record in Frigate Bird (1953) and gave further perspectives in The Sky Beyond in 1963. Some Government assistance was obtained. For this flight a war surplus RAAF Catalina PB2B2 (made under licence by Boeing of Canada) was chosen from a selection available at RAAF Rathmines on Lake Macquarie, and refurbished. Civil registration number VH-ASA was allocated and Taylor named it Frigate Bird II. An experienced small crew was obtained and the organisation ran ‘like clockwork’. The addition of JATO (Jet Assisted Take-Off) rockets was considered a necessity in order to get a greatly-overloaded Catalina out of restricted landing areas, particularly at Easter Island. The flight commenced at Rose Bay on 13 March 1951 and the total route was 13,600 km. Prime Minister Menzies welcomed the men home at Rose Bay and the ‘plane was presented to Taylor, who in 1961 presented it to the Powerhouse Museum in Sydney where, after restoration, was suspended from the ceiling of the Boiler Hall.

One final book came from Taylor’s pen – Bird of the Islands published in 1964. Even as he was bringing Frigate Bird II in to land on Sydney Harbour in March 1951 his plans were maturing for a unique flying boat cruise service in the South Pacific. He believed that a cruise through the South Sea Islands should become “an opportunity for real and personal contact with the people of the islands, leaving time for the surprising and unplanned”. His path on this venture was not smooth, as those around him found that the world of commercial transport now could not be easily influenced by one man’s original philosophy of life. Taylor’s final book is more an account of a daring idea in development, than one of a successful proposal brought to fruition: a way of saying that Taylor did not read the signs and had lost his influence to some degree.

To find the required aircraft Taylor travelled in 1954 to the BOAC ‘boneyard’ for flying boats near Southampton on the Solent. He had decided that the ideal aircraft now for him would be the Short’s ‘Sandringham VII’ class ‘boat, the final development of the ‘Sunderland’ aircraft flown by RAF Coastal Command. The De Havilland Comet was flying, BOAC had been converting away from boats to an all-landplane fleet. Taylor found one final example of the ‘Sandringham VII’ available. It was known as St George and had been built for the Bermuda-Baltimore run and the competition from Pan American had been too strong. It was a most tempting big ‘baby’ for Taylor with low hours and new Pratt & Whitney engines, as on the Catalinas with which he was so familiar. He paid the asking price. He named it Frigate Bird III.

Back in Sydney, places on the island cruises had been sold and a schedule arranged. Taylor writes lyrically in Bird of the Islands about the experiences, the welcomes, the pleasure and enlightenment gained by most of his passengers. But after two years he and his operations were caught out by issues of regulation, finance and guarantees. The business folded in 1958.

Frigate Bird III still exists at the Musee de L’Air et L’Espace at Le Bourget. A photograph taken at Dugny of that ‘plane in its dismembered state in 2013 has been supplied by an Australian aviation historian Ian Debenham, an Ambassador at the AMHF, to whom much credit is owed for detail in this narrative.

In a concluding short chapter of his book Bird of the Islands Taylor sadly concedes that the flying boat has been “replaced by land-based aircraft on trans-ocean and other international airlines because of its relatively slow speed and costly performance as a flying machine”. There are other limitations which he does not mention, but he finishes by saying that “the flying boat (is) an orphan, and an extremely dangerous and inconvenient orphan … they will never come back”.

Two years after publishing this sad conclusion to his life’s great work, Sir Gordon Taylor was gone.

Ave Atque Vale