by Peter Robinson

Marina Maumann guides the W211 Mercedes E-Class down the steeply twisting Camps Bay Drive, just south of Cape Town, South Africa. It’s 26 January 2005, and Marina and Mica Naumann are looking forward to celebrating their wedding anniversary over dinner. Today Mica is on his mobile rather than at the wheel and Marina is driving the 2002 E270 CDI, her birthday present to Mica.

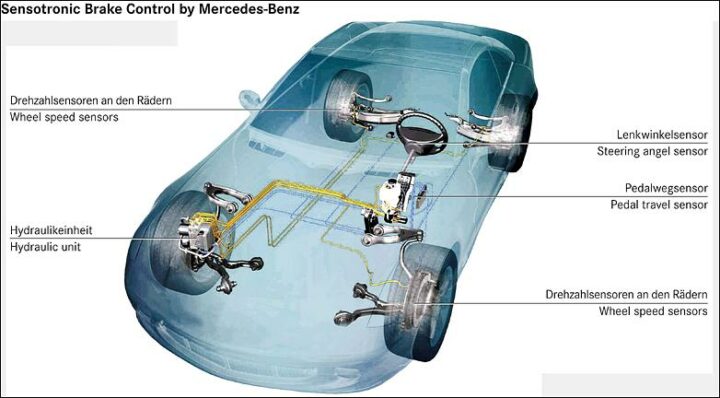

Without warning an alarm sounds, the instruments flash ‘Long Stop Brake Failure Stop Car’. Marina would if she could. The brake pedal turns soft, travel increasing if as there’s no connection to anything. The E-class’s once vaunted Sensotronic (SBC) electro-hydraulic brakes switch to back-up mode. With a spongy brake pedal and minimal retardation, there’s no chance of obeying the Houghton Road stop sign. Finally, desperately, Marina steers the Mercedes to a stop on the footpath.

Shaken, scared by what might have been, Marina knows she never wants to drive this Mercedes-Benz again. Mica turns the E270 around and points it uphill towards their garage. Transport for the evening is an ancient Isuzu bakkie (utility vehicle).

The Naumann’s were not alone in having brake problems with their E-Class. In May 2004 Mercedes recalled 280,000 cars equipped with the system. This was followed on 1 April, 2005, by a global recall of all 1.3 million cars equipped with the Bosch-built SBC system, introduced on the R230 SL and later fitted to the W211 E-Class, C219 CLS, Maybach and SLR.

In recall-speak, ‘On certain vehicles, the Sensotronic Brake Control system may

prematurely shift to the hydraulic back-up function due to deterioration of the

wiring harness or due to premature failure of the hydraulic pump.’

As a consequence, ‘In the hydraulic back-up mode, the driver has braking power sufficient to stop the vehicle, although greater brake pedal pressure is required and the brake pedal travel will be noticeably longer.’

The remedy: ‘Dealers will inspect, modify and replace the SBC affected components.’

Caught out by the cost and image damage of rectifying the issues, Mercedes returned the high-volume E-Class to conventional hydraulic brakes in 2006. Hit by global publicity over the recalls, Mercedes’ reputation took a beating. The fall from grace can be traced to the early 1990s board decision to retreat from the reality of its slogan, ‘Engineered like no other car’, combined with the moves to innovative electronic features before BMW. The result was a nightmare that sent customer satisfaction ratings plunging, tarnishing Mercedes’ hitherto pristine image, a process from which it took many, many years to recover. Some might even say the job’s not done yet.

For decades the E-Class had been the nucleus of Mercedes’ entire range and, because of its numbers (around 300,000 sold per year), the great profit generator. Hurt by the critical publicity, especially in Europe, sales of the E-Class plunged in 2004, hitting Mercedes profits. Production dipped by 31 percent as fleet buyers stopped ordering the Benz, just as sale of the BMW 5-Series took off.

Generations of so-called ‘over-engineered’ cars created Mercedes’ previously peerless reputation. These were models like the W124 E-class (early transmission issues aside) that had lived in the market for fully 13 years and the vault-like 1991 W140 S-class, the last model not impacted by the change in philosophy.

Traditionally, Mercedes always took a long time to bring a new car to market as the engineering-dominated company strove to perfect its products. But now the board wanted change.

‘There are two figures usually used by manufacturers,’ Dr Wolfgang Peter, who became director of R&D in 1985, told me in 1991. ‘Some take the time needed from the decision about its specifications to the customers; some use the time from the decision about the styling clay. If you take the first, we needed 5.5 years, if you take the second, we needed little more than four years. We should go down to 4.5 years for the first and maybe three year for the second.’

This from the man who added 18 months to the W140’s development time to include a V12 engine (to match BMW) in the line-up. It gets worse: development of the W140 began in 1981, the styling signed off in December 1986 with a proposed launch date of September 1989. It actually didn’t make it into showrooms until the spring of 1991, a decade after the car was first conceived. The heavy, expensive (it cost up to 25 per cent more than its predecessor) W140 was probably the best car in the world at launch, but that didn’t stop Peter from being moved sideways in 1992 because he’d allowed the development costs of the S-class to escalate 50 percent beyond the budget.

According to his successor, Dieter Zetsche, the W140 cost 15 percent more to build than its predecessor.

Mercedes’ new engineering chief came across from Freightliner, the Mercedes trucking company, despite having no passenger car experience. Unterturkheim trembled when Zetsche took up his position as the board member responsible for passenger car development on April 1, 1992. There was widespread resentment at a former trucking engineer turned manager taking over such a hallowed position, once held by the legendary Rudolf Uhlenhaut. One engineer is reported to have said bitterly, ‘With this truck background, Zetsche is the ideal person to develop the next S-Class.’

With the blessing of the board, led by new chairman Helmut Werner, Zetsche slashed two layers (from six to four) from the engineering hierarchy in an attempt to push down decision-making and introduced simultaneous engineering. He also created 40 individual teams who were responsible for development and testing and, most important of all, the costing of major components. He wanted cars more clearly defined, a firm price target, release date and projected sale volumes, so all the costs would be known before production start-up.

Unfortunately, one unintended consequence of Zetsche’s ‘centre concept’ was a massive loss in corporate engineering knowledge and a sharp decline in the long-held power of the engineers. All inevitable perhaps, but the speed with which the transformation happened proved too fast for the organisation.

Zetsche’s aim was a more flexible Mercedes, to reduce lead times and costs.

‘Our target is 38 months after the release of styling….in some cases it has been 50 months.’

Mercedes’ traditional vertical integration – no other European car maker built

its own automatic transmissions – was lessened. In one case buying in components and engineering skills from outside reduced costs by 50 percent.

Zetsche insisted such savings could be achieved while maintaining quality and technology levels, despite resistance from some engineers who still believed new models should be developed regardless of cost. One insider told me, ‘They still don’t know how to cost a car; they just don’t understand how to be cost-effective because they’ve never had the problem before. Until they start counting every pfennig from the beginning, it won’t change.’

This came just weeks after Werner introduced the term ‘over-engineered’ as a swear word in a widely reported speech that instantly produced nervous customers, especially in Germany. Dr Karl Holman, the man in charge of engine development, explained, ‘”The best or nothing” is to be modified to “The best for the customer”. This addresses the cost benefits. Our cars must become more valuable, but not more expensive.’

Jurgen Besinger, the man in charge of passenger car development, told me there wouldn’t be any less engineering, ‘but rather Mercedes should offer features that are more noticeable to the customer. We are criticised for being late because we want to be sure of reliability. But there will be no backing off in durability or testing.’

Zetsche arrived too late to make any real changes to the new 1993 W202 C-Class, successor to the 190. Yet, in a symbol of the revolution from an engineering to a marketing-led philosophy, he insisted that the traditional oil pressure gauge – fitted to every Mercedes for over 40 years – be replaced by a warning light. Otherwise, in the way it behaved and felt, the C-Class was an old-fashioned Mercedes with 47 percent of the car (by cost) made on the premises. Zetsche’s aim was to reduce that to 35 or 40 percent.

The C-Class motto was ‘More car for your money!’ – pure marketing speak rather than engineering philosophy and as clear an indication of the company’s new direction as you could imagine. To broaden the cost base and lift M-B from its traditional circa-550,000 annual production, Zetsche was also openly talking about a model below the C-Class (which became the A-Class), a replacement for the G-Wagon (that became the ML), and a small sports car based on the C-class (the SLK). All to be developed by a far smaller engineering group.

The first model to be developed under the new rules was the W210 E-Class. The board gave its final approval for the styling in February 1990 so, with a launch in mid-1995, it still took over five years development, though Mercedes claimed it was 20 percent cheaper to build.

From my first drive in the new model I was aware that some of the W124’s bullet-proof magic had gone: the doors no longer closed with a reassuring thunk, but a tremor; the rear doors emitted a sound similar to pulling the top off a soft-drink can when opened; the shut lines around the tail lights varied between the boot lid and the body; a small and cheap plastic hook clipped the spare wheel cover to the body; there was obviously more plastic than any previous Mercedes; and the lovely dampened ashtray release mechanism, which allowed said tray to present itself with exquisite grace when you wished to empty it, was notable only for its absence.

To be sure these were small changes, but so too were they significant for they betrayed that fabled Mercedes’ aura. More important still was the decline in drivetrain quality of any model without the silky six-cylinder engine. The new and coarse 2.3-litre four-cylinder petrol engine, still tied to a jerky four-speed automatic (rival BMW and Audis had five-speeds) was unacceptable, while Mercedes’ first rack and pinion steering (built by ZF) proved prone to serious rack rattle. When the E39 BMW 5-Series arrived a few months later there was no doubting which was the better car.

Understandably, Autocar magazine’s road testers decided the E230 was deserving of just three stars (of five). Later rust became a common problem.

Then came the revolutionary and controversial A-Class, the quality-challenged, American assembled M-Class SUV, the semi-sporty SLK and the decision to adopt innovative electronic features for the new SL and E-Class in an attempt to leapfrog BMW. Coming so soon after the move to build cars to a budget, it only emphasised Mercedes’ increasingly stretched engineering resources.

The W211 displayed a lift in build quality and drove the way you expected a Mercedes to behave. Except for the brake issue. In 2006 Mercedes extended the warranty to four years and 50,000 miles. In 2008, under a special service campaign, the Sensotronic brake system warranty was extended to an unprecedented 25 years with unlimited mileage.

Aware of the catastrophic brake failures that resulted in so many cars being replaced, Dr Thomas Weber, then Mercedes board member responsible for R&D, told me, ‘The recall sent a message to customers that they can trust us. If we have a problem they know we will fix it.’

Weber admitted the brake problem arose because vibration allowed the electrical harness to work loose, thus triggering a reaction from the engine’s electronic brain. The ECU slipped into a special failure mode that deactivated the electronic braking system. The recall fixed the harness more securely and the modification flowed through to the production cars. Tellingly, however, the new W221 2005 S-Class reverted to the more conventional hydraulic braking.

In April 2005, determined to prove the E-Class’s reliability and quality, Mercedes ran three zero-miles E320 CDIs at its eight-mile Texas speed bowl for 100,000miles each, the fastest averaging 139.699mph and breaking 22 international records. To ensure nothing went wrong, Mercedes ran two try-out tests over 100,000miles before it was prepared to go public with the record attempts.

‘We wanted to prove the electronics of our cars are of the same quality as the mechanical parts,’ Weber said, explaining the thinking behind the colossal effort.

‘Many of the ideas we adopted from consumer electronics. We realised that was a mistake. We now know not all were suitable for cars. We did test the components, though some of the testing was by suppliers. We’ve now been through all the electrical components in the car, part by part, with the suppliers.

‘But we now realise that you can’t just test the components by themselves. You need to test the whole car to see how they interact and are integrated together in one environment. That was our biggest lesson.’

As for the Naumanns, their E270 was trucked away to be replaced at no cost by a new E320 in September 2005. Until the new car arrived, Mercedes provided a loan car. They are not the only people to have their defective car swapped: I know of at least two SLs in Australia that were also replaced at no cost to the customer. How many cars were replaced?

‘Only a few,’ is all Weber was prepared to admit.

How is Mercedes’ quality today? Better, no doubt, however the US Consumer Reports says, ‘We expect the 2024 E-Class to be less reliable than other new cars. This prediction is based on Mercedes-Benz’s brand history and the previous generation E-Class.’ Reputations are a long time building and, it seems, rebuilding too.