by Peter Robinson

These were no ordinary family photograph albums. In the frescoed library of Contessa Camilla Maggi’s Calino home, among a stack of scrap books, you’d find a leather-bound, limited edition of photographs of her parent’s 1908 wedding. Another contains a series of aerial prints of the Calino villa and vineyards, there’s one of pre-WWI hot air balloons, a Brescia air show in 1912, elegant Bugattis, Lancia limousines, a 1910 yachting trip to Egypt.

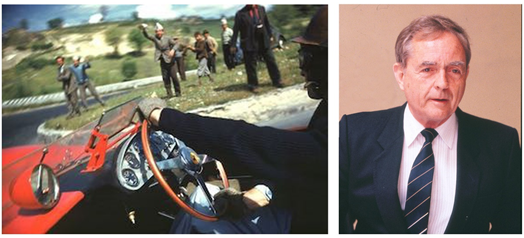

Among the pile are three albums of special appeal to motor racing fans. These contain fascinating photographs of generations of racing drivers, team managers and cars and, most of all, intimate pictures of the events surrounding the Mille Miglia, Italy’s, surely the world’s, great car race (1927-1957), that took participants from Brescia to Rome to Brescia on roads as old as Italy itself.

You see, in 1927 it was Aymo Maggi, Camilla’s husband, whose influence and enthusiasm created the Mille Miglia, the race of giants.

There are snaps of Tazio Nuvolari, Enzo Ferrari, Achille Varzi, Stirling Moss, Alberto Ascari, Alfred Neubauer, Donald Healey, John Wyer, David Brown, Tommy Wisdom, the brothers Marzotto, Giovanii (Johnny) Lurani, Peter Collins and more. Plus, a wonderful variety of racing cars from the 1920s to the late 1950s. This treasure trove comprises an album by the great photographer Louis Klemantaski and contains his classic photographs of various rides in the Mille Miglia with Peter Collins, and just as many of his less publicised, earlier run in an Aston Martin with Reg Parnell.

Contessa Camilla Maggi, who died in 2004 at 94, a charming, enthusiastic, generous woman, whose energy belied her age, lived through it all.

Camilla always played down her role in motor sport. “I know nothing about cars or racing,” she told me whenever the subject came up. Before launching into yet another story surrounding the car people who came to Calino and enjoyed her hospitality.

“There were no hotels in Brescia after the war (WWII) and my husband wanted to invite the foreign drivers to the Mille Miglia,” explained Camilla. “Donald Healey was the first to come. He stayed with us in Calino with his son Geoffrey. They raced a Healey with Johnny Lurani. Later, Healey suggested (journalists) Tommy Wisdom and Basil Cardew should come to Italy for the Mille Miglia. Little by little more people came. John Wyer, Gordon Wilkins, the Aston Martin team.” Each May, for at least a week, the Maggis’ palatial villa in the village of Calino, about 20kms west of Brescia, was thrown open to visitors and became the social heart of the Mille Miglia. The hospitality and dinners for the foreign entrants quickly became the stuff of legends. In those days it was difficult to get foreign currency and Maggi often lent visitors money without any expectation of being repaid. Sometimes the generosity flowed both ways. Tony Lago, who was born near Brescia and produced Talbot-Lago cars in France, lent the Maggis money when they visited Paris.

“Aymo bought a David Brown tractor for the farm (vineyards)”, Camilla explained. “A few years later, David (Brown who then owned Aston Martin) gave my husband a new one. He was very generous.”

Almost until she died the tradition of Maggi hospitality lived on. For the first few years of the historic rerun, Camilla hosted a party for the many foreign entrants on the evening before the renamed 1000 Miglia. Phil Hill, Oliver Gendebien, Stirling Moss and even minor royalty in Prince Michael of Kent, all enjoyed Camilla’s welcome. It was the evening before the 1987 event over a drink on the terrace of casa Maggi, that Walter Hayes, a former Ford PR-person and vice-president, first talked to Victor Gauntlet, then chief executive of Aston Martin, about the possibility of Ford buying Aston.

In 1995, to celebrate the 40th anniversary of his famed record-breaking win, Stirling Moss drove the Mercedes-Benz 300SLR to Calino to be reunited with ‘The Contessa’ in the villa where he stayed on the nights before the race and dined after he won.

“My husband fell in love with Stirling Moss’s driving when he came to Italy to race in the Circuito del Garda,” recalled Camilla. “Moss was so young he came to Italy with his mother and father. After watching Stirling drive, my husband said he was special, very fast and smooth, somebody to remember. He followed his career with Jaguar and always wanted to know what Moss was doing.”

At that first sighting in 1949, Moss, then 19, finished third in his heat, third in the final, and won the 1100cc class. It was the start of a long friendship: “Stirling had to get permission from Alfred Neubauer to sleep here for the three nights before the (1955) race.”

“He had to promise to be in bed by 8pm and to wake at 5am, because that was the time he would have to get up for the Mille Miglia. He didn’t want to go to bed while everybody was eating. There were too many women around and the others used to tease him about it. But Stirling always went off at eight.” Moss himself wrote: “One of the things I remember most about the Mille Miglia is the hospitality of Aymo Maggi and the Contessa Camilla at Calino. It was not to do with Aymo’s background of centuries of tradition, or with eating and drinking in pretentious style. It was just that we all thought that being at Casa Maggi during the race period was like being at home. The atmosphere was relaxed and friendly and I always had the firm feeling that if I stayed in Calino before the race I would be lucky on the day. Maybe it was a superstition – but then I always was very superstitious.”

In John Wyer’s book Racing with the David Brown Aston Martins (volume one, 1980), Wyer perfectly captures the atmosphere. “Casa Maggi was one of his (Aymo’s) many houses and he invited the entire Aston Martin team and, in fact, all the English contingent, to stay there for the duration of the race, and it was a style of living which one is never likely to see again. It was absolutely feudal, really, with livered flunkeys as every corner.

“The Contessa would come to me after dinner and ask what time we were going out to practice in the morning. I’d say, ‘Please Camilla, don’t worry about us. We’ll be getting up around 4.00am to leave at five for a dash down to Padova before there is too much traffic. I have an alarm clock, so I’ll wake the others and we’ll stop for some coffee at a café down the road. We don’t want to upset the household.’

“‘Don’t be ridiculous’, she’d say. ‘Of course, you must have breakfast – the servants will be very upset if you go out without it.’

“So, at four in the morning we’d all sit down with a footman behind each chair serving our breakfast – the same servants who’d been on duty till midnight, serving dinner and drinks afterwards. And there they all were in their white coats and gloves, serving breakfast at 4.00am. It’s a style of living I’m glad I’ve seen, for I’m never likely to see it again.

“The Maggis were wonderful people – I never found a language Camilla – the Contessa – didn’t speak. Before the race they’d have an enormous house party which included the British, French and German contingents and Camilla would carry on a conversation in five or six languages.”

Camilla Martinoni Caleppio was born in Brescia and her father was one of Brescia’s motoring pioneers: “He was great friends with the Florio family, who started the Targa Florio,” said Camilla. “They used to come to Brescia for the Cuircuito di Brescia, on the Montichiari circuit, which my father helped organise.”

The Maggis and Martinonis were also great friends. In the photograph of her parents’ 1908 wedding, which took place in the Maggi villa, you can see a five-year old Aymo watching events from a balcony window.

Camilla learned English from the family nanny but subsequently, in 1927, she spent a year at the Sacred Heart school in Putney, London. Later, she would translate for her husband who didn’t speak English. She could effortlessly, simultaneously, translate into French, English and Italian.

Growing up Camilla heard Aymo’s name because her mother played bridge with Anna Maggi, Aymo’s mother. But she took no interest when he became a works driver for Bugatti. “He used to visit the Bugatti works in Mulhouse and I know he won races, but I wasn’t interested in cars.”

In fact, Aymo Maggi had a flat in Molsheim and in 1926, in the new Type 35 GP Bugatti, he won the Rome GP, and races in Sicily, the Coppa Vinci and Coppa Catania, and at the Lake Garda circuit.

Then there was the Mille Miglia. “Brescia organised the first Italian GP in 1921 on the Montichiari circuit, but the people of Milan were jealous,” remembered Camilla.

So envious that the Milan Automobile Club, helped by Arturo Mercani, a Bresciano, built the Monza Autodrome circuit and ‘stole’ the Italian Grand Prix in 1922. “My father was so cross with Mercanti he never went to Monza, the people of Brescia were outraged.”

It was on the drive home from a hill climb in 1926 that Maggi conceived the idea of a road race for sports cars. With the help of his friends Giovanni Canestrini, a motoring journalist, Count Franco Mazzotti, an enthusiast and aviator whose family owned Isotta Fraschini, and Renzo Castagneto, who organised sporting events, these ‘four musketeers’ formulated the Mille Miglia to promote Brescia and the Italian motor industry. With the help of Augusto Turati, another Bresciano and the secretary general of the Fascist party, Maggi obtained approval to hold the race on public roads. The red symbol 1000 Miglia, still used for the retro event, became well known around the world after the first race in March 1927.

Maggi drove a 7.4-litre Isotta Fraschini with Bindo Maserati (one of the six Maserati brothers) in that first Mille Miglia and finished sixth. But once the great race grew in importance Aymo found that he had little time for other events. His final full season as a driver was in 1930 when he drove an Alfa Romeo 6C 1750 in the Targa Florio and finished eighth in the Mille Miglia in the official Alfa team that included Achille Varzi.

Aymo Maggi married Camilla Martinoni on April 23, 1931, by which time he’d inherited his family’s estates and the title of Conte Maggi di Gradella.

“After the Mille Miglia became successful, Aymo lost interest in racing,” Camilla told me. He had two Bugattis when we were married, one was a blue GP car. His friends wanted him to stop racing, so he sold them both and bought a Pininfarina-bodied Lancia Dilambda.

After the war the mayor of Brescia persuaded Maggi to restart the Mille Miglia and English visitors began to come to Calino. Thus the Contessa became an integral part of the event. With Charles Faroux, the influential French motoring journalist, Maggi organised a special cup for the driver who did best in the Mille Miglia and Le Mans.

“I was there in 1955, the year of the dreadful accident,” Camilla remembered. “Neubauer explained Mercedes was frightened Moss and Fangio would race each other so they put them in the same car for Le Mans.”

The Mille continued through the 1950s: “Every year, Aymo thought it would be the last, he was nervous something would happen. We were in Brescia when the news (of Fon de Portago’s fatal accident) came through. Aymo was devastated. He was happy Taruffi won the Mille Miglia after 15 tries and it was the last (in 1957). After that he lost interest. People came and talked about starting it again as something different, but he wanted to leave it alone.”

Aymo Maggi died in October 1961, aged just 54. Doctors said he died of a heart attack; those who know him say he died of a broken heart.

In 1988, my old friend and colleague at Wheels magazine, Mel Nichols, then Editorial director of Haymarket Magazines, asked if I’d create the role of European editor for Autocar magazine, the world’s oldest motoring title (1895). We could live anywhere in Europe, except the UK. Germany would perhaps have been a more logical location, but it was always going to be Italy.

When Athol Yeomans, Wheels’ first editor, heard of our plans and our intention to live somewhere near Verona, in Italy’s north, he insisted we stay in Santa Stefano. Athol and Ian Fraser, Wheels’ third editor, rented the house, built around a tiny chapel on a hill that overlooks Calino, from Camilla Maggi.

Athol asked if we’d pay homage to the Contessa. We rang and Camilla invited us for a drink. All scrubbed up and a touch apprehensive, we ventured down to her villa, to be greeted by Franco, her butler, wearing white gloves and carrying a tray of glasses of the local champagne. We told Camilla of our plans, though she scoffed at the idea we’d find a home via real estate agents.

“I have a friend whose son is an architect, he’ll know of a home,” she assured us, not quite understanding the logic. Sure enough, two days later we were shown a villa, on the other side of the village, that was to be our home for the next nine years. By 1998, when we moved to our own newly renovated home just three kms from Calino, Camilla had become our great friend and mentor. How fortunate was I, as a motoring writer, to meet Camilla’s many motoring friends on a personal level. People like Olivier Gendebien, Louis Klemantaski, Stirling Moss, Victor Gauntlet, Phil Hill, Froilan Gonzalez and Gianni Marzotto. Stories inevitably followed (https://motorheritage.org.au/olivier-gendebien/; https://motorheritage.org.au/louis-klemantaski/).

And those albums? “When my husband was ill, after the Mille Miglia finished, I suggested he should put all the photographs in albums and identify the people,” Camilla explained. “It gave him something to do.”

Where are they now? I’ve no idea. A grand-nephew, with no interest in cars or motor racing, inherited the estate. I can only hope these priceless albums remain in the library.

A couple of years before she died, Camilla leased her vines to the Tuscan wine makers Marchese Antinori. Today, you can buy ($50) a Contessa Maggi Franciacorta sparkling wine. They say it’s “every bit as refined and elegant as the name it bears.”