by Andrew Moore – – –

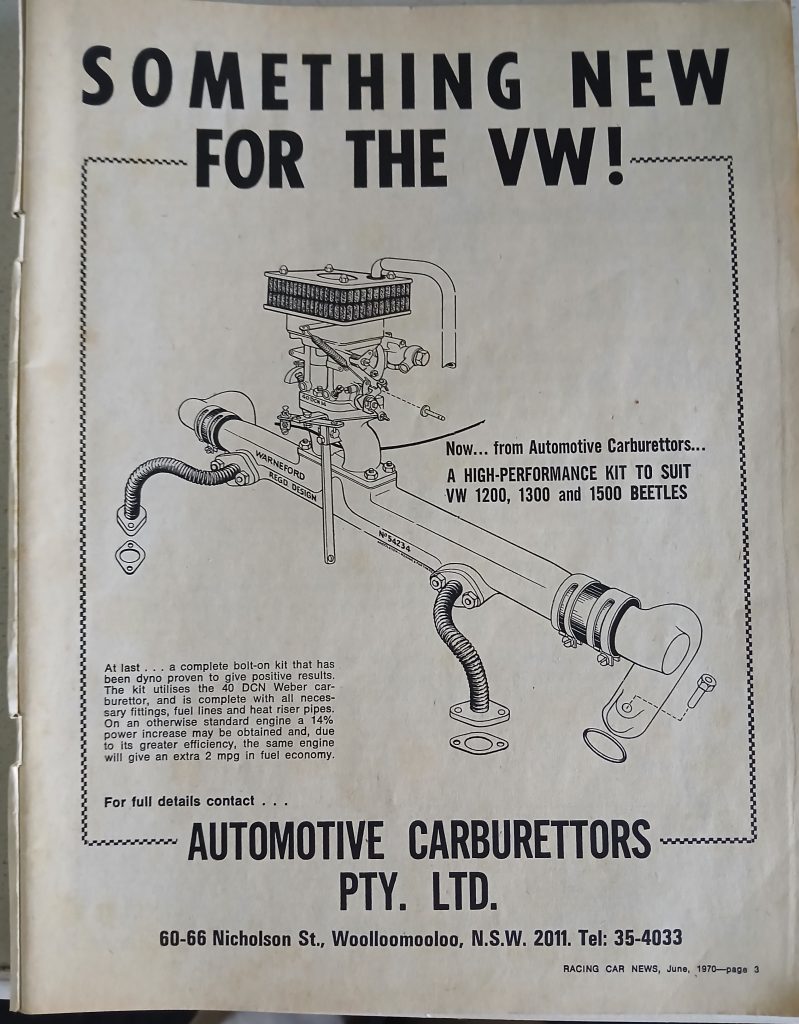

For those of us who read Racing Car News in the 1960s and 1970s, the name Warneford may strike a chord of recognition. No issue of RCN was complete without an advertisement for a Warneford product. They made some pretty good kit, particularly manifolds for carburettors. Many a hot Holden burbled along with a red engine fitted with twin carburettors feeding through a Warneford manifold. In 1977 there was brave talk of expanding their spare parts offerings to the United States market. Then part of the Borg-Warner group, Warneford Industries, even won two export awards for selling to the US.

The little Aussie battler behind Warneford Industries, Walter John Warneford, recently appeared in John Smailes’ history of Phillip Island. Smailes discusses the career of Bill Thompson, Australia’s first professional motor racing driver. In the 1932 Australian Grand Prix at Phillip Island, Warneford was the riding mechanic for Thompson. When an oil line behind their Bugatti’s dashboard split, Warneford’s quick action saved the day. Tying a rag around the split and pinching it shut with his fingers, for 29 laps Warneford effectively held back a tide of red-hot oil with his bare fingers. Wal’s fingers were so badly burned that he did not hang around for the prize-giving ceremony after the race. Instead, he was rushed off to seek medical attention.

It was a typically gung-ho moment in Warneford’s adventurous life. Clippings, including an article in Wheels, April 1954, in his biographical file in the papers of Graham Howard held in the library of the Australian Motor Heritage Foundation, shed further light on the ‘Wild Ways of Wally Warneford’. It seems that before the 1932 AGP at Phillip Island he, Thompson and Bill Northam indulged in a harem scarem road race through the streets of central Melbourne. Unmuffled, with engines roaring, brakes and tyres screaming, their three cars, two Bugattis and a hotted-up Austin 7, reached speeds of over 80mph.

Understandably, the Melbourne cops were unimpressed. Several police officers pursued the trio to their hotel. Warneford was not fazed. Bumptiously, he told the policemen that no less than the Victorian police commissioner, General Sir Thomas Blamey, had given permission for the cars to be used in the city with only straight-through exhaust pipes fitted. The police, it seems, knew of this concession. However, they also knew that Blamey had stipulated that the cars could only be driven from the Melbourne Docks to Phillip Island in their unmuffled state. He never authorised hooning around the inner-city. The cops ordered Wally and his two mates to desist.

Born in Sydney in 1909 or 1910, as a young man Walter Warneford* reputedly aspired to become a surgeon. The finances of a working-class family could not support that goal. Apprenticeship to a firm of electricians was his lot. As early as 1927 there was a business styled Warnefords Car Electrical Ltd operating out of premises in Lane Cove Road, Crows Nest. Curiously, however, Wally was given to describing himself as a ‘psychologist’. A conduit to motor racing occurred when Charlie East, who prepared and tuned Bill Thompson’s racing cars, gave him a couple of magnetos to rewind. Wal began to spend much of his time hanging out at Bill Thompson’s garage in William Street. Nominally, he was working as a mechanic. More than likely, he was not paid. As the Great Depression hit, Thompson’s business was at a very low ebb. In the absence of paying customers, Thompson spent much of his days chatting to his mates. Wal was happy to join in and when Thompson moved to cheaper premises in Kensington, Wal was willing to help and stay on, no doubt hoping that a paid job might result. It did not, but the connection to Bill Thompson proved to be Wal’s entree into the hard-drinking, colourful world of 1930s motor racing. His reputation as a tuner extraordinaire and larrikin began to grow.

Nor was motor racing Wally Warneford’s only claim to fame. Unknown to the motor racing historians, Wal also worked as an undercover policeman. Indeed, he established some notoriety in that role.

As social unrest increased at the height of the Great Depression the NSW Police was concerned about the possibility of civil disorder. Apart from their traditional foes, communists and leftists, there was a new kid on the block. This was the so-called New Guard, the right-wing brainchild of Sydney solicitor Colonel Eric Campbell. The New Guard ultimately became the Australian equivalent of Hitler’s SS or Sir Oswald Mosley’s Blackshirts. Avowedly Fascist, they planned to mount a coup d’état against the State government of Jack Lang by storming Parliament House in Macquarie Street. To their great credit, the NSW Police did their level best to rein Campbell and his men.

Among the measures the police adopted against the New Guard was to pursue undercover surveillance and disruption of the New Guard through its Criminal Investigation Branch. (There was no ‘political’ Special Branch at this time.)

It is unclear what the job description of ‘psychologist’ meant in the 1930s, but that is how Wally described himself in electoral rolls and also when he appeared in a court case relating to the New Guard. Perhaps because of an interest in studying the human mind rather than any credentials or background as a sleuth, Wally Warneford joined the police shadowing squad. His quarry was the New Guard.

While his reports, to the present day held in State Records of New South Wales, do not suggest he uncovered many of the New Guard’s secret plans, Wally was kept busy moving around the city hoping to pick up intelligence, chewing the fat with his contacts in various pubs, coffee shops and public parks. Often Warneford worked in tandem with a well-known policeman, Frank Fahey, aka ‘The Shadow’. Best remembered for his part in solving the international possum skins scandal, Fahey owned a motorcycle with sidecar that was cleverly modified to include a periscope. This allowed discrete observation of suspects. Reputedly, this worked well, though being ensconced in a small sidecar for many hours must surely have been a claustrophobic experience, not to mention an exhausting one on hot days.

On 6 May 1932 there was a celebrated assault by an inner group of New Guardsmen known as the Fascist Legion. The target was one J.S. (‘Jock’) Garden, secretary of the NSW Trades and Labour Council and one of Premier Lang’s inner circle. In the eyes of conservatives and members of the New Guard, Garden was the devil incarnate and the principal architect of Premier Lang’s plans for socialism in New South Wales.

The assault happened at Garden’s suburban home, 42 Cooper Street, Maroubra, at 2.00am. The scene resembled an American gangster movie set in interwar Australia. Two large limousines cruised to a halt and silently discharged their cargo of eight men. Four men crept through an adjoining vacant allotment and jemmied a paling loose from the side fence before advancing up a passage leading to the property’s back door. The others marched more forthrightly to the front door and knocked, announcing themselves as police officers searching for a prowler. Having obtained access to the house, and despite the brave defence mounted by the family Airedale, the gang of eight men set about their task, intimidating the household and bashing Jock Garden.

Garden was not seriously injured by the assault. Nonetheless, he suffered bruising over much of his body, as well as abrasions and a wound on the back of his head. His wife and daughter fainted during the attack. Debated among historians to the present day, the incident became the New Guard’s most trademark deed.

If the New Guard hoped to be praised for the assault, they were to be disappointed. The sense of eight goons invading a man’s house in the middle of the night, causing distress and injury, triggered widespread community outrage. For the sporting journal, The Referee, the home invasion was an example of inappropriate masculinity. ‘A “Red-blooded” man is a bloke full of pugnacity to defend female virtue and the honour of the Flag’, it argued. ‘The New Guard is composed mainly of red-blooded men – so are all basher gangs and lynching parties’.

At first, Eric Campbell supported their actions, describing the attack as ‘highly desirable’ and the assailants ‘decent and thoroughly loyal’. Subsequent police inquiries, however, brought to light disturbing revelations about the clandestine ‘Fascist Legion’. To reinforce their anonymity at meetings they wore Ku Klux Klan-style hoods and gowns (lovingly sewn by their wives). It transpired that the group was organised around a system whereby each member adopted the title of a playing card. The ‘Fascist Legion’ had also been known as the ‘Pack of Cards’. It consisted of 49 men, led by ‘The Joker’. Given the homophobic sensibilities of 1930s Australia, queens were omitted. It was all seriously weird.

Public opinion turned quickly against the New Guard. Indeed, the bashing served only to discredit the New Guard. It did this so effectively, however, that Eric Campbell and others argued that the assault was a cunning ploy carried out by the police. In this conspiracy, Wally Warneford was ascribed a central role. It was claimed that Wal had planned and carried out the assault with the connivance of some members of the police and certain ministers of the Lang Government. Their purpose had been to discredit the New Guard.

Unsurprisingly, the allegations of conspiracy were amplified in the sensationalist newspapers of the time. Truth melodramatically claimed that the slightly built and bookish Warneford was an ‘international investigator and soldier of fortune’, as well as a ‘champion boxer… (and) dead shot marksman’. He was known, within the Fascist Legion, Truth suggested, as the ‘Knave of Clubs’ who had inspired members with talk that ‘used to freeze their blood with stories of deep deeds, adventure and revolution’. Truth even claimed that Warneford had been lurking in the bushes outside Garden’s house on the night of the assault, commanding the New Guardsmen to advance and then fleeing the scene.

Warneford was later called as a witness to give evidence in the trials relating to the assault charges brought against the New Guardsmen. In court he disclaimed any part in the planning or perpetration of the assault, while also tendering the dubious claim that he was a ‘phychologist ‘(sic) who resided in Darlinghurst.

Archival evidence suggests that Warneford spent the night of 5-6 May 1932 in the company of his mate Frank Fahey. Taking advantage of many sly grog shops’ proclivity to serve two thirsty policemen outside trading hours (pubs then closed at 6.00pm) the pair travelled around various seedy nightspots on Fahey’s motorcycle and sidecar. Their claim to be having supper in the cafeteria at the Central Railway Station between 2.00 and 2.30am on 6 May 1932 was corroborated by several independent witnesses. They were nowhere near 42 Cooper Street, Maroubra when the assault took place.

Notwithstanding his innocence, in the eyes of the New Guard, Wal Warneford became Public Enemy No 1. Shortly afterwards, at a New Guard rally in the Sydney Town Hall, there was a near riot when Wal boldly intruded upon the meeting as part of a police contingent. No doubt the intention had been to start an altercation. By this time the police were anxious to assert their superiority and there were several police ‘riots’ where they took Campbell’s New Guardsmen on. Like Liberty Vallance, Colonel Campbell was being taught about the fate of those who take on the law.

Despite the excitement of winning the 1932 AGP in such dramatic circumstances, much of Wal Warneford’s subsequent life proceeded less eventfully. Following the AGP, Warneford looked around for a car to race in his own right. Unable to afford a top-ranked Bugatti, with Jack Clements he bought a wrecked one, rebuilding the body and overhauling the engine. The car’s crankshaft, however, let the pair down in the following year’s AGP. Instead, they set their sights on setting and breaking interstate speed records, between Sydney and Melbourne in particular.

A popular genre of motor sport at the time, using the public roads as racetracks was, however, increasingly frowned on by the police. The NSW Police Commissioner specifically instructed Warneford and Clements to desist. They ignored him. Leaving Sydney’s GPO, the speed demons had to outrun a police car that had been sent to stop them.

While they may have succeeded in breaking the one-way record between Sydney and Melbourne, upon their return to Sydney the pair was paraded before the NSW police commissioner.

By this time (1935) the commissioner was W.J. MacKay, a braw Glaswegian, who was tasty with his fists and happy to use them as a negotiating tool. Big Bill was also no fan of motor sport. It was largely at his sayso that post-war motor racing at Parramatta Park was banned.

Wally Warneford knew MacKay well from when he was an undercover policeman with the CIB. Superintendent Bill MacKay had been its head. In any case Wally was not intimidated by the presence of the large, hulking and angry Scot in a police interview room. He stood up for himself. ‘There’s no law that says you can take my license’, he insisted. Big Bill was not anxious to debate the point. According to the Wheels article, ‘the enraged Commissioner took only a minute to convince Warneford that he could have him boiled in oil. So the driver promised to be good’.

In the 1930s Wally Warneford established a reputation for being a tuning whiz, the first port of call for racers wanting extra speed for road or track. He briefly dabbled in speedway. In 1947 he opened a tuning shop in East Sydney and the business styled Automotive Carburettors. There he quickly established a reputation as the expert for tuning carburettors and high-performance engines. Apart from manifolds he was clever at designing ancillary related bits and pieces. These included an air cleaner that used a polyurethane element, the first in the world.

By this time, no doubt reflecting the increased prosperity the business had brought him, Wal moved to Sydney’s North Shore where, with wife Doris, he raised a family of his own, several members of which became motor racing aficionados. His son, Peter, was chief scrutineer for the Bathurst 1000 touring car race in 1989. In 1974 Wally sold his business, Warneford Industries, to Borg Warner. He had plans to resettle in retirement to a farm in Mudgee but died on 9 August 1976.

For genealogical research I am grateful to Jan Piper.