by Brian Caldersmith

I always admired Colin Chapman and his designs, especially from an engineering point of view. Breakthrough after breakthrough, advancement upon advancement, was routine in the development of his cars. Few people caused a law change because of their designs, and I know of no other whose cars were banned because they were too fast (Lotus Sevens in American sports car racing). I always wanted a Lotus and to me, the epitome of that philosophy, with perfect styling, was the Elite.

There were very few in Australia, so the Elite was not easy to come by. Nor were they cheap. Then chance came my way.

Barry Bassingthwaighte used his Lotus Elite as his daily driver until, one day in 1973, it caught fire as he arrived home from work. Fortunately, he was able to extinguish the flames before the fibreglass car burned to the ground.

However, there was severe damage within the engine bay and surrounds. Barry decided he’d had enough of the car and wanted to be rid of it. After a tip off, I took one look at the Elite and bought it on the spot for $900.

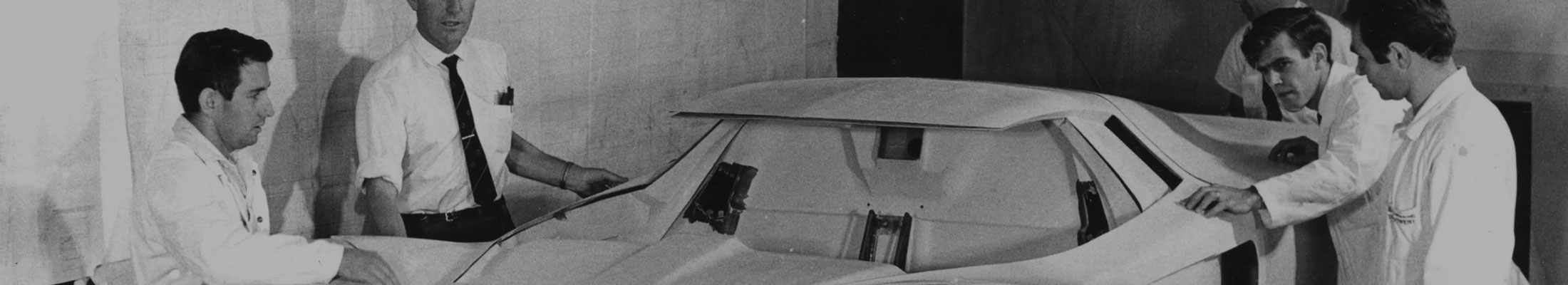

From the outside it didn’t look too bad, but the restoration/rebuild took many years after I got it home. Work commitments were heavy with lots of travelling and our growing family was taking priority, so progress was intermittent with random bursts of activity when funds were available. But I had an advantage that no other owner enjoyed. My brother Tony worked at Lotus in the early days and had helped build the 12 pre-production Elites with two other guys and ended up as the Lotus Service Manager before returning to Australia. Product knowledge par excellence.

The rebuild involved removing everything from the car to expose the bare shell so that the fibreglass repairs could be made to the engine bay and other damaged areas. That work was done by the guru of that medium, Sam Johnson of JWF fame. The entire body was then rubbed back through several colours of paint down to the gel coat before it was ready for repainting. All the componentry was stripped and rebuilt or replaced (new wiring harness, windscreen, seats repaired, all new bolts nuts and washers) Nothing was left untouched.

Initially, the Elite was registered for the road and I drove it often, including touring events like the Dawes Classic. But that activity reduced with time and as the racing built up. When conditional registration became available, I transferred to this system, which was more suited to its usage, and enjoyed the subsequent cost savings.

For those who don’t remember. the Lotus Elite was released at the Earl’s Court Motor Show in London in 1957 and caused a sensation. It was way ahead of the times – it was the first composite monocoque, had four-wheel disc brakes (inboard at the rear), full independent suspension, an all-alloy engine, and a drag coefficient of just 0.29. Inevitably they found their way into racing and were very successful, winning their class at Le Mans six years in a row, and twice the Index of Thermal Efficiency among a string of successes including the Australian GT Championship in 1960.

Historic racing in Australia was expanding rapidly in the 1970/80s and that’s where I decided to use my car. For 30-years we raced at most circuits in Australia: from Mallala in South Australia to Lakeside in Queensland, including the inaugural historic meetings at Sandown Park, Oran Park, Phillip Island, Wakefield Park and Eastern Creek – and the final meeting at Amaroo Park.

The car was a delight to drive and very forgiving, resulting in class lap records and a memorable three outright wins at an atrociously wet Oran Park (all due to the car’s outstanding handling).

There were only two DNFs in that time – once when I got hit from behind and pushed into the kitty litter, and once with an engine failure (after the first 14-years of racing).

The car was essentially neutral in its handling with a touch of understeer initially, but beautifully balanced. You could induce oversteer if you lifted off the throttle in the middle of a corner – which was handy from time to time.

At 654kgs and with four-wheel discs, you could out brake most cars. I took delight in rushing past rivals going into corners… while still on the throttle.

I set myself a limit of 7500 rpm to protect my bank balance (the overseas guys use 8500rpm). Yes, there were occasional bursts to 8000rpm in the frenzy of competition, but it had a wonderfully flat torque curve and you weren’t really achieving a lot by extending beyond 7500rpm

My preference was for long distance races rather than five lap screamers (which is why I promoted and introduced them into historic racing with the HSRCA). They are much better for the car AND the driver. Besides, many drivers find that when they drop their rev limit 500rpm (because they are going to be out there for some time) they end up lapping at the same times as when using higher revs. Everything gets smoother and the action seems to happen more slowly.

The Elite and I were a partnership for 45-years and I owe it a great deal. I have enjoyed friendships and experiences I would not have encountered without the car and the historic racing camaraderie.

Unlike professional motorsport, in historic motor racing people will try everything they can to beat you on the circuit, but they will also do everything possible to help you be on the circuit. Among those are some well-known names: Sir John Whitmore (who shared my car at meetings), Ian Scott-Watson and Chris Barber, all three with direct Elite connections – and too many locals to mention. My car has been featured in many magazines and a book or two, so it became well-known from its first race at Warwick Farm in 1963 to the present day.