Two books, reviewed by Garry Pritchard and Hugh King

The Library at the Australian Motor Heritage Foundation holds two books from the first decade of the 20th century, with contemporary accounts of the aviation activities of an extraordinary man.

Santos-Dumont (1873-1932) was a Brazilian aeronaut, sportsman and inventor, and is said to be one of the few people to have contributed significantly to the early development of both lighter-than-air and heavier-than-air aircraft. His work My Airships (1904) describes his interest in lighter than air aircraft.

Santos-Dumont was born into a wealthy family of coffee producers in Brazil. There is no explanation as to how he funded the development of his airships but there always appeared to be money for him to proceed with his next project.

As a child Santos-Dumont was fascinated by the idea of flight and was introduced to ballooning as an 18-year-old on a family trip to Paris. Back home in Brazil he determined “I am going to Paris to see the new things – steerable balloons and automobiles”. Arriving back in Paris he did not have the financial resources to engage in ballooning so became involved in motoring where he successfully introduced motor–tricycle races in Paris. This gave him the experience in due course to build petrol engines for his airships.

A Frenchman Henri Giffard had built a rudimentary steerable balloon in 1852. Despite a few attempts, by the early 1890s no “cigar – shaped balloon had been seen in the air”. Santos-Dumont managed to talk himself into a flight with a balloon manufacturer and thereafter spent most of his time up to 1904, when the book was written, in Paris developing his range of airships. Initially his interest was in “round” balloons that were at the mercy of the winds, but over time he became more interested in the “dirigibility” of airships, that is, their susceptibility to control.

To make his first controllable cigar shaped airship, called “No 1”, he made his own lightweight engine which gave him the ability to control the direction of its flight. “It was astonishing to feel the wind in my face. In spherical ballooning we go with the wind, and do not feel it”. His airships progressed from No 1 to No 10, each time adding new features or correcting old ones. It is not clear whether he actually built number 10 which was a large airship designed to carry up to 12 passengers. His favourite was No 9, “the little runabout” which was a one-person design that he used for the personal pleasure of flying around Paris. He records one instance when he took off from his base near the Bois de Boulogne and flew to his apartment on the corner of the Champs Elysees, where he landed, had locals hold the airship while he had morning coffee inside his apartment, and then flew back to his base.

In 1900 the Deutsch Prize of 100,000 francs was offered for the first dirigible balloon or air-ship to leave the Aero Club at St Cloud, circle the Eiffel Tower and return within half an hour. In October 1901 Santos-Dumont won the prize, which by then was 125,000 francs, plus a further 125,000 francs from the Brazilian government. He divided the Deutsch Prize money among the “deserving poor” and his employees.

He was from his own account a feted person in France and he often drew large crowds when he flew. In 1902 the Prince of Monaco built him a hangar in Monaco which enabled him to fly in a more temperate climate and learn to fly over water.

Some of the developments that he incorporated into his airship flying were:

- While in round balloons he would fly as high as 2,000 metres, in his dirigibles he flew mostly at a low level of about 150 metres with a rope trailing on the ground. If the airship rose, the additional weight of the rope would then bring the airship back down until the weight of the rope counterbalanced the weight of the airship.

- He initially rode in a basket under the airship. He then developed a “canoe” that was suspended below the main bag. In the canoe he had a seat, the motor, and the rudder and he was able to move backwards and forwards on it for balance and to operate the motor and control ropes.

- He acquired his own hangar and hydrogen plant so that he would not have to deflate an airship after a flight and then reinflate it for the next flight, at a substantial cost for the hydrogen.

In the book he gives some insights into motoring in his day: “This very day all the highways of France are dotted with a thousand automobiles broken down, with their enthusiastic drivers crawling underneath them in the dust, oil-can and wrench in hand, repairing momentary accidents. They think no less of their automobile for this reason”.

In 1902 he took trips to England and the United States. His views on their approach to the development of ballooning and motoring contrasted significantly with the attitude of the French.

In England and America it is quite different. When I take my airships and my employees to those countries, build my own balloon, house, furnish my own gas plant, and risk breaking machines that cost more than any automobile, I want it to be done with a settled aim (to win prizes). To win prizes, then I waited long in London and New York; but as it never passed from words to deeds, after having enjoyed myself very thoroughly, both socially and as a tourist, I returned to my work and pleasure in the Paris which I call my home. And really, after all is said and done, there is no place like Paris for airship experiments. Nowhere can the experimenter depend on the municipal and state authorities to be so liberal.

Take the development of automobilism as an example. It is universally admitted, I imagine, that this great and peculiarly French industry would not have developed without the speed licence which the French authorities have wide-mindedly permitted.

In the same order of ideas I may here state that, in spite of the tragic airship accidents of 1902, I have never once been limited or in any way impeded in the course of my experiments by the authorities.

These comments may give an insight into the attitude that set back aircraft development in the US after the Wright brothers flew in 1903 – largely due to the Wright brothers’ patent disputes which dragged on for many years and which were ultimately only resolved by the US government in the First World War.

The book was originally published in French in 1904 with the title “Dans l’Air” and has been republished in 83 editions to this date.

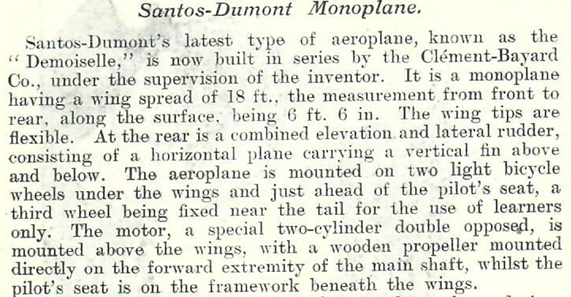

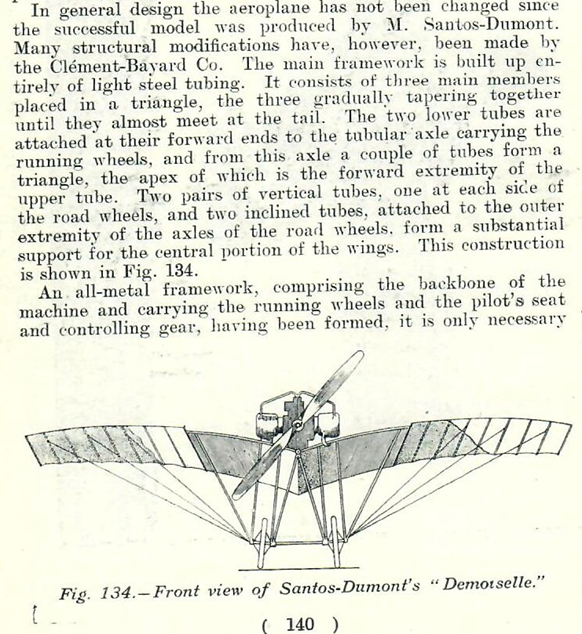

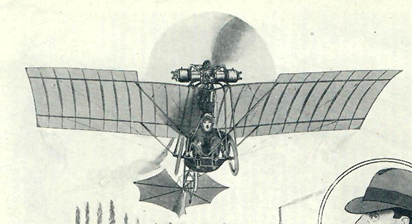

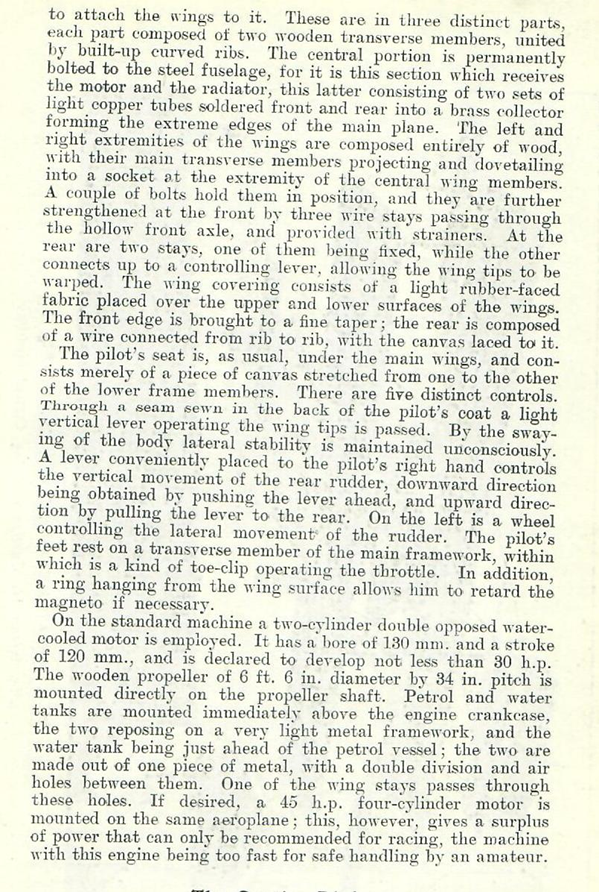

Thereafter our pioneer developed his interest in fixed-wing, heavier-than-air craft and a major success with his monoplane Demoiselle in 1909-1910. Here we scan a full description of that important development, taken verbatim from The Aero Manual of 1910 (second edition).

The quality of the scan is not professional-grade, for which the reviewer apologises, but the specifications are set out. The style and sophistication of this little machine set a trend.

* * *

- My Airships, author Alberto Santos-Dumont, published 1904 by Grant Richards, London; and

- The Aero Manual, compiled by the Staff of ‘The Motor’, published 1910 by Temple Press, London

Garry Pritchard

Hugh King