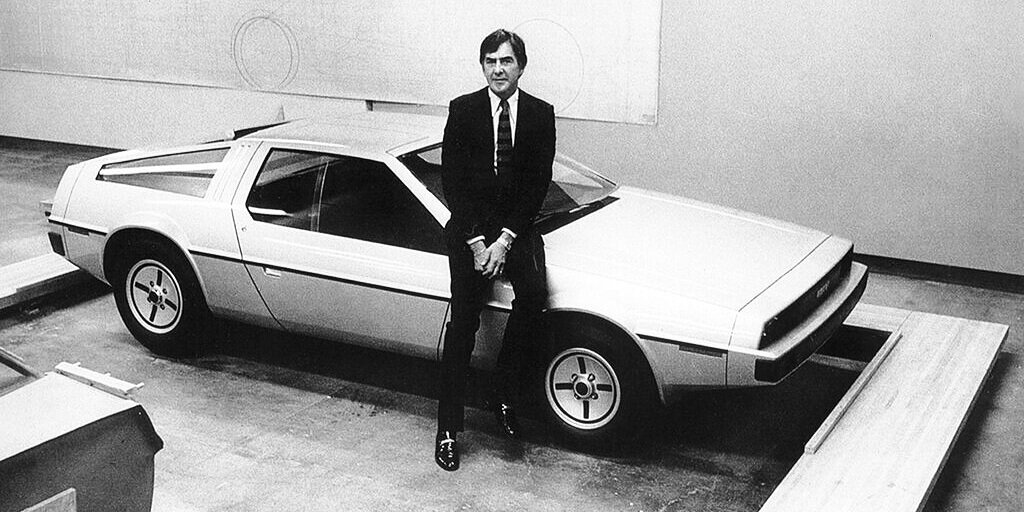

It’s now over 40 years since my first and only encounter with the controversial John Zachary DeLorean, father of the famous eponymous gullwing sports car.

In February 1981, having organised to attend the Arizona launch of GM’s new ‘import buster’ J-car (the front-drive Holden Camira), a contact learned that Delorean planned the first public showing of its much-anticipated DMC sports car in Los Angeles. The timing was perfect, given that it was just two days before the five GM divisions individually unveiled their look-alike versions of the J-car. Invitation arranged, GM Holden’s chief engineer, the genial Joe Whitesell, who’d worked for DeLorean in his glory days at Pontiac, kindly wrote to DeLorean at his 280 Park Avenue, New York headquarters, on my behalf.

That Sunday, February 8, 1981, the grand old Los Angeles Biltmore Hotel provided the perfect backdrop for the 600-odd guests who squeezed into the Crystal Chandelier Room for the National Automotive Dealers’ Association conference. For the 340 American DeLorean dealers invited to the reception the cars were paramount: potential buyers queued fretfully for access to a single car on the floor or stared longingly at the two DMCs circling slowly on podiums in the middle of a vast array of exotic food. The cars, flown from Belfast where they were specifically built for the function in DeLorean’s new British Government funded factory, represented one twelfth of February’s production.

At that stage the US release date was whispered as late April and the rumoured $25,000 price tag – almost $10,000 more than a Corvette – seemed not to be hindering the enthusiasm of the many trendy young male customers who, armed inevitably with a Farrah Fawcett (remember her?) clone, all decided they just loved the sleek lines of the DMC. Even if, on snuggling down into the beautifully finished and equipped interior, they discovered visibility was restricted in most directions and that they could not close the gullwing doors without help from outside.

Under the constant glare of multi-coloured lights, a six-piece jazz band played popular hits of the ‘60s above the eating, drinking and chatter. Periodically the band gave way to the sound of a violin and harp played elegantly from the balconies – at which times guests were delighted to discover they need not shout to be heard above the music.

Information about the DMC was non-existent. Instead, glamourous Hollywoodish women from DeLorean Motor Cars handed out a pretentious 10-page document entitled “DMC ….A Break With Tradition.” Apart from the silver profile on the cover, the brochure (along with a couple of DMC labelled paper napkins, I still have a copy somewhere) made no reference to the car. As an alternative to a description or specifications, it detailed the work of various craftsmen, hoping readers would make the obvious connection. And surprise, surprise, the very people mentioned in the booklet just happened to be going about their business on the edge of the room surrounded by small knots of people casually interested in their work.

Dr James Bruno, violin maker, James Sherwood, master tooler and Alice March, hand weaver, played out their roles quietly, doubtless thinking of the dollars. Activities that had zero to do with the car. In the brochure, sections regarding their creativity were interspersed with quotations from the likes of Abraham Lincoln, Jane Austen and Williams Shakespeare.

Unacknowledged, but from Act Two of the Bard’s The History of Troilus and Cressida, came:

“She is a theme of honour and renown

The spur of valiant magnanimous deeds

…and fame in time to come.”

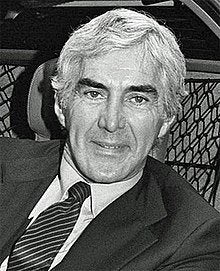

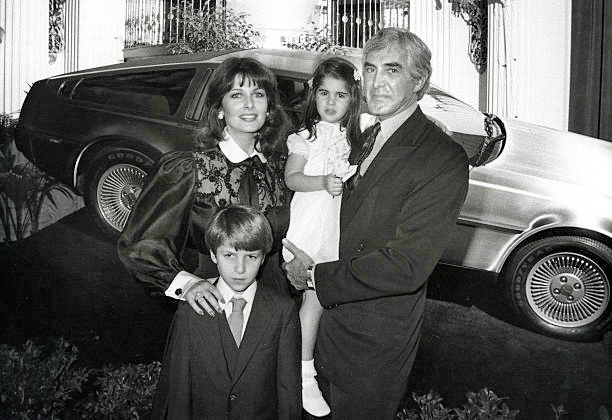

It was the figure of John Zachary DeLorean that completed the brassy cast. Tall, silver-haired, accompanied by wife number three, the model Cristina Ferrare, plus son and daughter, he worked his way around the room using either a dignified solemn expression or plastic smile to greet the adoring throngs who wanted so much to meet the six-foot four star who, “Looked like a million-dollar picture star,” according to Hollywood producer Pierre Cossette, “like he had been put together by the property department of MGM.”

It was the figure of John Zachary DeLorean that completed the brassy cast. Tall, silver-haired, accompanied by wife number three, the model Cristina Ferrare, plus son and daughter, he worked his way around the room using either a dignified solemn expression or plastic smile to greet the adoring throngs who wanted so much to meet the six-foot four star who, “Looked like a million-dollar picture star,” according to Hollywood producer Pierre Cossette, “like he had been put together by the property department of MGM.”

As a curious journalist I’ll admit to being one of them. Delorean remembered Whitesell, but seemingly not his letter. Nor was he interested in talking about the DMC. The fixed expression on his artificial face didn’t change during our 90-second conversation, only that his eyes constantly sought out more appealing company than this pushy Australian journalist.

Late in the night a battery of photographers cleared a little space around one car and the four members of the family stood beaming as flashlights recorded the great occasion. The distant, detached and inaccessible appearance of the man behind the DeLorean vanished only for those few moments. They repeated the shot with Johnny Carson, a popular TV show host. Then he was engulfed by the horde again.

I came away from the Truman Capote-style extravaganza convinced that these Californians, all having a drink on Margaret Thatcher and the British Government, would buy the DeLorean for as long as salesmen could spin out its enigmatic exclusivity and no longer.

On returning to Australia, I talked to Joe Whitesell about his former colleague. Joe reminded me that he had been a great and innovative engineer who taken Pontiac and, later, Chevrolet to higher than ever sales and profits. But when promotion took him to the fourteenth floor of the headquarters – then the sanctum sanctorum of the global car maker – he didn’t fit in. DeLorean went from having 90,000 people working for him as Chevrolet divisional manager, when that really meant something, to being a corporate vice president, earning $(US) 650,000 (about $8m today) with just an assistant. Instead of making fundamental product decisions, he was presented with a choice of this or that proposals for new models. His influence gone, the flamboyant DeLorean found he ran counter to GM’s management culture.

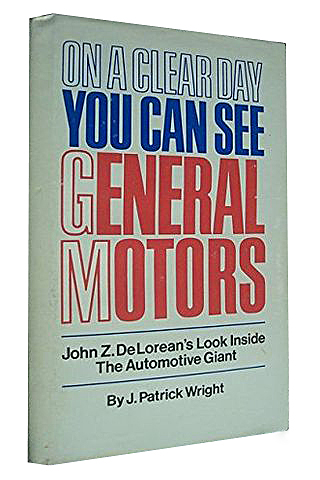

His gossipy, yet tell-all book about GM – On a Clear Day You Can See General Motors – is still worth reading for its insights into a huge, bureaucratic corporation. Written with J. Patrick Wright, a former Detroit Business Week bureau chief, it was held back by DeLorean for four years over concern it could impact on his raising money for the Delorean car project.

His gossipy, yet tell-all book about GM – On a Clear Day You Can See General Motors – is still worth reading for its insights into a huge, bureaucratic corporation. Written with J. Patrick Wright, a former Detroit Business Week bureau chief, it was held back by DeLorean for four years over concern it could impact on his raising money for the Delorean car project.

We all know how that ended, so there is no need here to go into the troubled development of the DMC or the DeLorean drug bust and entrapment case, which he won. John Z. DeLorean died in 2005, still dreaming of building yet another take on his own sports car. His tombstone shows a depiction of his DMC sports car with the gull-wing doors open.

For many, the highlight of that first public showing of the DMC production car was a small nuggety man who spent the evening walking around with a life-size porcelain beagle clutched firmly under his arm. No, I’ve no idea.

PETER ROBINSON