On October 24, 1969 Fiat paid one lira (around 0.6cents) to gain outright control of Lancia. That one lira was merely a symbol of course, for Fiat also inherited Lancia’s debts – totally many hundreds of millions of lire. The sudden fall of Turin’s most respected car maker came as a surprise to most people. Those in the Italian motor industry knew that Lancia was in trouble but nobody anticipated the extent of its predicament or the speed of its fall.

Ingegnere Sergio Camuffo was shocked when he read the news on the front page of La Stampa that morning, and wondered briefly what his masters at Fiat would do with the 63-year old car company. Within days of the takeover, Niccolo Gioia, the general director of Fiat asked Camuffo, who was the Fiat 130 project engineer, to join what was left of Lancia’s depleted engineering staff as technical director. He was given the task of deciding Lancia’s long term product plan.

Camuffo, whom I interviewed in early 1990 for my Heroes’ column in Autocar magazine, found a company so run down through lack of money that many of its finest engineering brains had left. Lancia’s product range had become dated – the flagship Flaminia dated back to 1957 and their newest model – the Fulvia – to 1963. The cupboard was bare of new models and staff morale in the pits. Financial controls were virtually non-existent: Fiat’s financial analysis of the much-admired Fulvia and Flavia models revealed that they cost two to three times more to build than the equivalent Fiat. They were beautifully engineered – some said over-engineered – but Lancia lost money on every car it built during the 1960s.

Lancia’s engineering department watched anxiously as Camuffo considered his options. The first idea was simply to merge the two companies, put Lancia badges on the more upmarket Fiat models, to make use of the still prolific Lancia dealer network, while gradually converting Lancia’s relatively new and costly Chivasso plant to Fiat production.

A more measured view, strongly pushed by Camuffo, recommended an opposite course. He asked for two years: enough time to replace – first – the older and complex Flavia and, much later, the smaller Fulvia, which meantime would benefit from Fiat’s expertise at reducing manufacturing costs.

Camuffo was given both the time and the money to formulate a cohesive strategy. First he moved to arrest what was becoming a mass exodus, convincing key engineering staff to remain; including chassis engineer, Romanini, and engine chief Ettore Zaccone Mina – the engineer responsible for the Fulvia’s marvellous, narrow angle (13deg) V4.

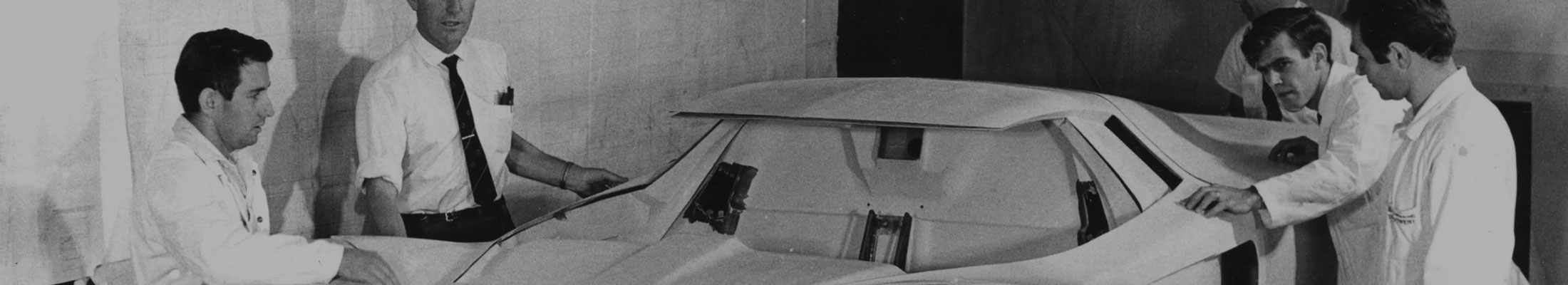

His team, fired up with new-found enthusiasm after months of uncertainty, concentrated their efforts on the new mid-sized sedan, but simultaneously began development of a big Lancia sedan to replace both the Flavia/2000 and the Flaminia. To save much-needed time they decided to adapt Fiat’s twin-cam relatively new and excellent 1.4, 1.6 and 1.8-litre engines to a transverse layout for a new two-box sedan to be designed by Fiat’s Felice Mario Boano (most famous for his work at Ghia where, with Luigi Segre, he designed the Lancia Aurelia, VW Karmann-Ghia, before moving to Fiat to work on the 600 and the Simca 1000).

Within months, a Flavia sedan, concealing Camuffo’s advanced suspension concept was being tested. The engineering principles behind MacPherson strut suspension for all four wheels were simple: light weight, easy to adjust and with exceptional ride comfort and excellent high-speed stability. Their only real weak point was that the rear spring/strut towers needed plenty of space.

At the 1972 Turin Motor Show, Lancia unveiled its Beta sedan. Much underrated (at least until its rust problems surfaced in northern Europe later in the decade), the Beta’s lightweight construction (1000kg) endowed the car with excellent performance and economy. Comfort levels were high in its roomy, trendsetting body and, everyone agreed, it retained much of the precious Lancia dynamic character. Between late 1972 and 1984, when it was phased out as the facelifted three-box Trevi, production of the Beta sedan variants reached 247,483. Nor does that figure include the 195,414 Beta Coupes, Spiders and HPE models that drew their mechanical inspiration from the same platform (all but the Spider were officially sold in Australia). Through the 1990 and 2000s, Camuffo’s basic suspension philosophy continued not only in many Japanese and US cars, but also in Lancia’s Thema and Delta.

Simultaneously with development of the Beta, Camuffo was working on the new big Lancia sedan (Tipo 830). During the early ‘70s Fiat’s affair with Citroen blossomed to the extent that this car – which would ultimately become the Gamma – started out using Citroen’s hydropneumatic suspension and was planned to be twinned with Citroen nascent CX. For a suspension engineer like Camuffo, the opportunity to create the Gamma with Citroen’s help was understandably, compelling.

Three prototypes were built, using Citroen suspension adapted to the Lancia floorpan. The irresistible Lancia inclination to be different led to the birth of a new water-cooled flat-four engine of either 2.0 or 2.4-litres. Camuffo still maintained that this engine layout brings a lower centre of gravity and permits a lower bonnet line. Then, when it seemed the Fiat-Citroen deal would come off, the merger was cancelled, some say because French President, Charles De Gaulle, opposed the use of French technology in an Italian car.

“We lost a year,” remembered Camuffo ruefully. Pininfarina modified the new car’s styling, the basic layout of the Beta’s suspension was adopted and in late 1975 the Gamma was launched to an indifferent press. Some found fault with the car’s styling, others felt any true luxury car deserved a bigger engine with more cylinders. A flat-six had been considered but was too long, Production was delayed by a year but it was still launched too early. Soon reports of engine trouble began filtering back from Italy. In Lancia’s rush to production the assembly of the engine’s rubber belt drive for the camshafts hadn’t been checked correctly. What worked perfectly in the prototypes was too difficult to duplicate on the assembly line and the belts slipped, causing major engine havoc. Another year was lost in completely renewing the internals. Camuffo defended the car. “The Gamma was born at the wrong moment, it was a desperately unlucky car.”

Camuffo’s 20-years involvement with Lancia extended to all the models except the mid-engine Monte Carlo, which was intended as an upscale Fiat X 1/9 and only became a Lancia late in its development,. He worked on the Stratos, having analysed exactly what was needed to win rallies. With its ultra-short wheelbase, the Ferrari V6-powered Stratos was far too powerful to put is power down through the front wheels – the original intention – so a mid-engine layout was quickly adopted.

Having failed with the Gamma, Lancia set about defining a new small luxury car. Using Fiat Ritmo engine/gearbox, the Delta evolved. There was a move to make it even smaller but Camuffo resisted the temptation. It was he who proposed a turbocharged 2.0-litre engine for the high-performance version – leading to the birth of the brilliant Integrale.

Camuffo retired in 1989 and died suddenly of a stroke in January 26, 2014. He was 88. He lived long enough to witness the sad, terminal, decline of Lancia, with Citroen the most innovative of all car makers.

Pathetic, American Chrysler models badged Lancia were never going to revive the once great marque. Today they’ve deservedly disappeared and Lancia is left with just the Ypsilon, a tiny city car, essentially sold only in Italy. Sales in 2018 were around 44,000. Why bother?