by Peter Robinson

Forty-nine years ago, upon becoming the editor of Wheels magazine, I discovered a pile of manuscripts written by Griffith Borgeson. The name was familiar, I dimly knew the by-line from American magazines like Car & Driver and True’s Automotive Yearbook and vaguely remembered tales on Bonneville, the Miller front drive Indy cars, Bugattis and so many of the fascinating people involved in the world of cars.

Eventually, I delved into the stack of stories and instantly realised they embraced a wonderful variety of subjects, all beautifully written, sharply drawn and displaying what I came to understand was Borgeson’s trademark precision and brevity. One, especially, was a minor masterpiece. The evocative story of Erich Maria Remarque’s Lancia Dilambda first appeared in Motor (August 20, 1969). Remarque, author of the definitive World War One novel All Quiet on the Western Front, used the Dilambda to escape from the Nazis on three occasions.

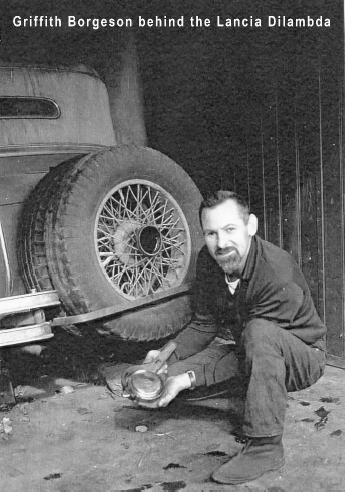

The V8 Dilambda, a rare and fantastic Lancia featuring a 24-deg 4-litre V8 engine, was launched in 1928. Borgeson stumbled upon the car by accident and, questioning as always, found its owner. The encounter with Remarque, now married to the beautiful actress Paulette Goddard, the former wife of Charlie Chaplin, led to a unique story rich in passion and adventure as well as cars, that memorably began, “This I swear is exactly the way it happened…”

Who was this American, apparently living in Italy, with an unmatched ability to combine cars and people to create the most inspiring stories?

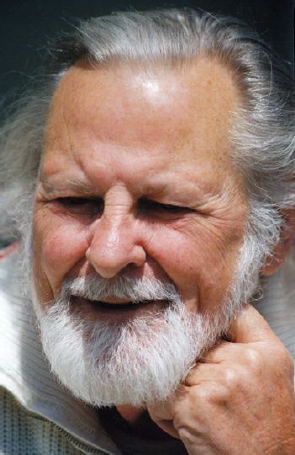

I wrote to the address at the top of the manuscript only to have the envelope returned from Turin “not known at this address”. Finally, after a few dead-end leads, I wrote to an address in Aix-en-Provence in the south of France. Thus began a long correspondence, for I quickly learned that Griff was an inveterate letter writer. I made the first of many visits to the Borgeson’s “ancient, rustic manor” in November 1973, staying with Griff and his delightful wife Jasmine and discovering he was everything his writing suggested; curious, intellectual, independent, intense, controversial, enthusiastic, a little spoiled, and extremely knowledgeable.

Griffith Borgeson was born in Berkeley, California on December 21, 1918, into a stimulating family with a real interest in cars. The family owned a string of fine American cars: an EMF (later Studebaker), Packards, Franklins and an HCS, which his mother always referred to as the Harry C. Stutz, out of respect for its ancestry. Griff learned to drive in a Buick and Model-A Ford. Smitten by seeing a T40 Bugatti in 1931, he later told me his life was ‘wrecked’ by seeing a Mercedes-Benz SS and the realisation that the two European cars were entirely different from the American models he was used to. His first car? Not for Borgeson a rough Model-T Ford, but a Mercedes ‘Nurburg’ phaeton, the marque’s first eight and a model developed by Ferdinand Porsche. Griff was 16.

At high school Borgeson took a journalism course and contributed a weekly column to the school paper. He developed an interest in Mexico and took a program in Spanish, to the point where, fresh out of high school, he founded the first daily Spanish radio program in Northern California. The language skills developed and, as they moved from country to country, he (and Jasmine) later became fluent in Italian and French, naturally switching from language to language when the nuance of meaning was better explained by a word in another language.

During WW2, Griff worked as a marine machinist in the merchant marine and then as a test engineer for Kaiser shipyard. His break in motoring journalism came when he wrote to the new Hot Rod magazine and received a reply on the letterhead of an unknown magazine, Motor Trend. Walt Woron, MT’s founding editor, asked Borgeson to contribute an historic piece for the first issue, September 1949. More stories followed and eventually he joined the staff, but by mid-1952, yearning to be independent, Borgeson went freelance. Editors knew he was too valuable to lose from the masthead and through the 1950s he held influential non-staff positions with Sports Cars Illustrated and after the name change, Car & Driver.

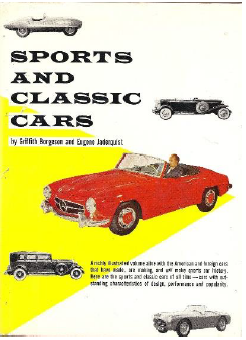

Borgeson’s first book, Sport and Classic Cars, written with Eugene Jaderquist, was published in 1955 and introduced a generation of American enthusiasts to the history of sports cars. It was also one of the first books to devote any space to what were becoming known as classic cars. Other softcover books followed, most devoted to various aspects of the booming fascination for Hot Rods.

In 1954 Griff came across an article by J.D. Scheel in Bugantics, the British magazine of the Bugatti Owners Club, about two front-drive Miller 91s that were lying around as little more than scrap at the old Bugatti works at Molsheim. The supercharged, eight-cylinder, 1.5-litre cars were known as the Packard Cable Specials: American racing was already heavily into sponsorship in the late 1920s (the sponsorship was by General Motors Packard Electric Division, not the Packard Motor Car Company).

Realising the Leon Duray cars’ unique role in the history of American racing – in 1928, Duray set the Indianapolis lap record at 124.018mph, a speed not exceeded until 1937, the longest the record has ever remained unbroken – Borgeson tried to interest wealthy collectors in saving them, but to no avail. Finally, after a couple of years’ trying, he knew he would have to rescue the cars himself. Decades later, Borgeson would proudly say the saving of the two Millers was his most significant motoring achievement.

Jean Marcenac, a riding mechanic for the Ballot team in the ‘20s, who’d worked on the cars with Duray in 1929, also told Griff about the Millers – how Ettore Bugatti had swapped three Bugatti T43 road cars for the two 91s in 1929 in order to learn about front-wheel drive after seeing them perform in the wet at Monza and Montlhery. But Bugatti still didn’t understand how the CV joints worked and when the four-wheel drive T53 came out in 1932, it used ordinary joints of the front drive-shafts. Inevitably, this meant the steering was extremely heavily. Only two or three T53s were built and within a year it was dropped from the Bugatti catalogue. Ettore also wanted to understand twin-cam engines and tore down and analysed the engines, adapting the Miller’s top end design for his own use on future Bugatti engines.

Eventually Griff persuaded Bill Ziff of their significance and the publisher of Sports Cars Illustrated lent him the money. In October 1958, with Marcenac acting as an introduction, he wrote to Bugatti and after drawn-out negotiations finally arranged to pay $(US)2500 each for the two cars. Pierre Marco, general manager of Bugatti at the time, was happy to see the last of the ‘junk.’

American Express transported the cars to the USA in return for publicity and in July 1959 they arrived in the Los Angeles port in a large box. Borgeson, who met the cars at the docks, says they were exactly as they had been when last used 25-years earlier: still in Monza colours and covered in dust, the castor oil having turned to glue. One car went off to the Indianapolis museum where it was restored. The second was rebuilt by Borgeson, who worked on it full time for six months, including taking the engine apart and putting it back together in his living room. Later he wrote about the project in a series called ‘Project Time Machine’ in Car & Driver.

By the late 1950s, Borgeson was keen to leave the USA. After a short spell in too humid Jamaica, the Borgesons moved to Europe in 1963, first to Turin and a couple of years later to Aix, where the Provencale weather reminded him of California.

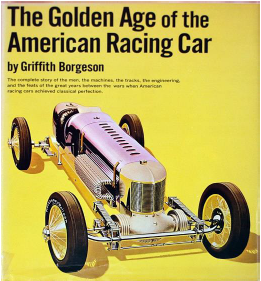

It was in Aix that Griffo, as he preferred to be known, wrote The Golden Age of the American Racing Car, a still sought after classic that rescued the memory of American racing from 1910 to 1930 and covered personalities like Fred Duesenberg, Louis Chevrolet, Harry Miller, Leo Goosen and Fred Offenhauser. The work was a best–seller and winner of the Antique Automobile Club of America’s prestigious Thomas McKean Award, one of a number of awards Borgeson collected.

Shortly after the Borgesons moved to France, Griff meet Roland Bugatti, Ettore’s second son of his first marriage. Bugatti, who lived in the area, alerted the Borgesons to Camagne Mirail, in Griff’s words, “an enchanting, centuries old gem of a house.” To buy the house, Borgeson sold the Hepburn Miller to Bill Harrah, the casino owner who ran a famous motor museum (now the National Automobile Museum) in Reno, Nevada. Eventually it was bought by Robert Rubin who donated it to the Smithsonian Museum in Washington DC. According to the Smithsonian website the car, “is currently not on view”.

Borgeson’s first story for Automobile Quarterly, The Charlatan Mystery – the story of Ernest Henry and the true origins of the twin cam-engine – appeared in the third quarter of 1973. Two years later founder and publisher Scott Bailey appointed Griff European Editor of AQ. The high-quality, hard-cover ‘magazine’, with an international audience of serious car people, allowed Griff the time and expenses money for travel while conducting his meticulous research. Borgeson’s ability to speak French, Italian and Spanish (and read technical German) proved a huge advantage for an automotive historian working in Europe.

After the Miller story, the most meaningful ingredient of Borgeson’s automotive life had been, he told me in 1991, “an involvement with people and things Bugatti which has enabled me to see through much of the myths and folklore to present a more accurate picture than the traditional highly romanticised one. This is important because of the essential greatness of the name. To exaggerate and embroider the myth is to degrade him.”

The result was his 1981 book Bugatti: The Dynamics of Mythology. The same year The Classic Twin-Cam Engine was published, dedicated to his wife Jasmine and to William F. Bradley, the pioneering automotive historian “chronicler extraordinary, whose role in automotive history was more important than we shall ever know”. The book remains essential reading to anyone interested in knowing the truth about the creation and evolution of the twin-cam engine.

Under Bailey’s stewardship, Borgeson’s contributions to AQ were vast in number and predictably ground-breaking in research. They included a true scoop: In the Name of the People: the origins of the VW in which Griff revealed, for the first time, crude Beetle-like drawings signed ‘A.H. 33’, together with notes by Adolf Hitler from a meeting between Ferdinand Porsche, his automotive adviser Jakob Werlin, and Hitler in Berlin in 1934. Of the sketches and documents, purchased by AQ, Borgeson wrote, “We have reason to be assured of their absolute authenticity.” Like much of what Borgeson wrote for AQ, the VW article later grew into a book.

His AQ interviews, meticulous research and insightful analysis gave us the reality of Ettore Bugatti and his cars, Enzo Ferrari, Harry Miller, Ernesto Maserati, Vittorio Jano, Battista ‘Pinin’ Farina, Juan Manual Fangio and E.L. Cord. Borgeson’s interview with Enzo Ferrari in Automobile Quarterly’s Ferrari: The Man, the Machines (1975) is generally considered the most incisive of all the hundreds ever published on a man who was, says Borgeson, “so complex you can’t judge him by ordinary standards.”

Then came his monumental Errett Loban Cord: His Empire, His Motor Cars, also published by AQ. A comprehensive history on the life and cars of entrepreneur, E.L. Cord. This magnificently produced book was printed in a limited edition of about 2,500 copies and in 1983 sold for $(US)395.

In 1986 Bailey sold AQ to CBS, publishers of Road & Track and Car & Driver magazines. Borgeson continued his work for AQ, but too soon realised it wasn’t the same and came to realise that he’d been cossetted by Bailey. Within months CBS had offloaded the title and it was to pass through a number of hands before the last issue was published in 2012, when AQ was a shadow of Bailey’s magazine.

In August, 1990, Borgeson wrote to Senior Editor Jonathan Stein, “I began working for AQ in 1973, and all was correct under Scott. With each subsequent change of editors and owners, operating procedures have changed radically, and almost invariably with my having to learn the new M.O. the hard, indirect way. You are a witness.”

The relationship gradually deteriorated and, in a February 25, 1991 letter, Stein, wrote, “Griff, when we prepare one of your stories, we invest four to five times more energy and hours than for any other author’s materials. We return far more material for review, consult more frequently, and spend vastly greater sums on phone and expense bills. We do this out of respect for you and your work.”

Borgeson finally severed the relationship in June 1991, though his interest in automotive history and his writing hardly slowed down. He was appointed to the FIA’s Historic Commission and only stepped down in 1996, a year before he died of a sudden heart attack in June 1997. Throughout his life he owned many interesting cars: in California an Arnolt-Bristol, the Fiat 600 that was the Borgesons’ transport when they found Remarque’s Lancia, a 1932 English Ford Y with handsome French coachwork body but an inoperable engine (Griff found a complete engine at a Ford dealer in Scotland), a Peugeot 204 Cabriolet, a Pug 305 and, inevitably, a Citroen 2CV van.

For this Robert Caro of automotive journalism, there was no alternative but to finding the original source whenever possible, seeking out the old, the rich, the famous and even those who, initially, weren’t prepared to talk. In his exhaustive pursuit of truth, Griff was prepared to spend days examining documents page by page in following the clues, tracking down any leads and prepared to go back and forth to verify opinions. Borgeson accepted nothing at face value and was obsessed with avoiding repeating errors or unconfirmed information, the “twisted truth” he called it.

He was equally as pedantic about his writing: precise, careful to get the punctuation and the choice of words as close to perfection as possible. This precision created problems with various editors for he demanded galley proofs and hated any changes. “How do you expect the readers to understand what I am trying to say if they delete a comma?” Jasmine remembers him saying.

Jasmine, whom Griff meet in 1959 when she was working at Motor Trend and married two years later, remembers Griffo as a man with encyclopaedic knowledge. “A quick glance at his library attests to the extensive range of what which interested him: archaeology, geology, astronomy, history of arts and of music, architecture, the origins of technology of many fields such as clocks, firearms and many other fields. His curiosity was limitless.”

In AQ’s obituary Car & Driver’s former editor (and now respected historian), Karl Ludvigsen, said of Borgeson, “I take my hat off to him for the way he got his teeth into one subject and kept digging and digging until he got it completely. It was the thoroughness, the way he would go after work until he was satisfied. When he was satisfied, there were no more questions.”