by Peter Robinson

If Nigel Tait had followed the family tradition, he’d have worked in the music and entertainment industries. For over 70 years, the five brothers Tait – Charles Tait, the eldest brother, Nigel’s grandfather – brought Australians some of the world’s best musical and theatrical attractions, including My Fair Lady and Joan Sutherland. Grandfather Charles also wrote and directed the world’s first full length feature film, the 1906 The Story of the Kelly Gang, Nigel’s grandmother playing Kate Kelly, and his father, aged six, was an extra.

Ivan Tait, Nigel’s father, loved cars but true to the family custom worked in the music industry, in his case for 53-years. Ivan drove a 1920s Fiat, then a Rover P3 and P4, and Jaguar 3.8 Mk2, “a lovely car” Nigel frequently drove, and, in his later years, a Citroen DS. There were no other family influences, though grandfather Tait either owned or had friends with interesting cars. One, a French DFP competed in the 1921 Alpine Rally, then one of Australia’s top motoring events.

Ignoring the music heritage, Nigel, always fascinated by mechanical objects and in love with bikes and cars, instead choose a career in engineering, beginning at Repco during the golden F1 years. As the family’s Black Sheep, this Tait went on to become custodian, and then curator, for Repco, of the Brabham BT19 that won Sir Jack the 1966 World Championship.

Nigel’s first car was an Austin 7, bought for 10 pounds – “all the money I had” – when he was 15, which came after a succession of motorbikes, all ridden illegally, as was the way in the 1950s.

“The engine was in pieces, so I had to assemble and install it,” remembers Nigel. “I could then run it around the garden at home and soon, up and down the road outside our house. Once I was chased by a policeman in a Morris Minor.”

The copper followed Nigel home and wandered in. Having found the offender, he suggested Nigel wait until he had a licence and a registered car. That didn’t deter the young enthusiast.

“With friends we’d take the 7 and some motor bikes down to Kooyong Park (Toorak) near the tennis courts and spend hours careering around on the grass. We’d then proceed, unlicensed and unregistered, to drive the few miles back home.”

Nigel’s introduction to motor sport came in his early teens watching the TQ midget races at the old Garfield Speedway (later Drouin Speedway) track. He then started going to Tracey’s Speedway, Maribyrnong, on Saturday nights. Most significantly, one 1959 Sunday, Nigel’s father took him to the Ballarat airfield circuit.

“To this very day I recall admiring the beautiful (Murray) Carter Corvette with its polished aluminium body,” says Nigel. “Without doubt this was the spark that led to the lifelong love of motor racing and fabulous cars”.

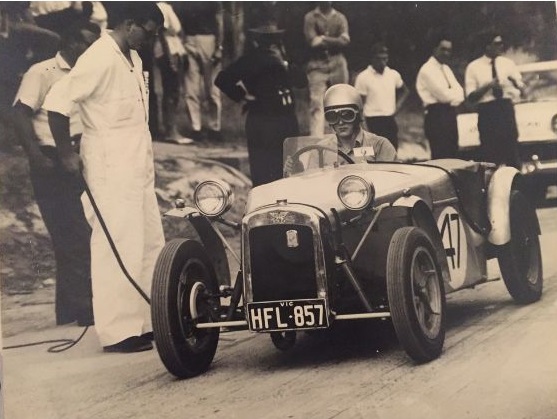

As a teenager, Nigel regularly competed in his first Austin 7 special and watched on as several friends in the 7 Club purpose built racing cars that conformed to the Austin 7 Formula (at its basis the UK’s 750 Formula).

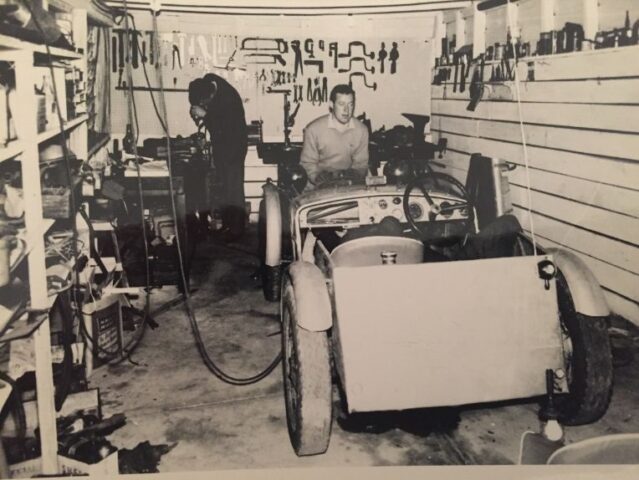

Says Nigel, “The Austin 7 soon lost its body. Having joined the Austin 7 Club and made friends with members already racing, hill climbing, and competing in gymkhanas and autocrosses, I started to turn the car into one conforming to the A7 Formula. Of course, while this was all in progress some “field testing” was needed.

“The chassis had been rebuilt with the chassis rails boxed in to add rigidity, then the practice. I’d bought an oxy welding kit and made all the new frame and body. Many parts were also made in the mechanics club at my boarding school, any items that needed polishing were completed during sermons in the school chapel.

His friend John Whitehouse took one such car to England where it cleaned up against the many Austin Sevens running in their “750” Formula.

“Without John knowing”, Nigel admits, “I secretly built my second car, similar to John’s. Upon his return, when we both turned up at Winton, he was shocked to see it. We had some great dices, my car was quicker, John the better driver.”

“But we virtually killed off the Austin 7 Formula. I was then competing against much faster cars in what would now be Group L and M&O (two historic racing categories). So, I fitted a Hillman Imp engine, resprayed it Yellow Blaze, same colour as my company car, Ford Falcon, and widened the wheels to take second-hand Formula Ford slicks. That slashed Winton short track times from 1.16.8 (still a record for A7s) to 1.8.8.”

Secondary school over, Nigel studied mechanical engineering at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT), completing an associateship diploma of Mechanical Engineering and a Fellowship Diploma of Automotive Engineering.

Having graduated Nigel claims, “I was lucky enough to con my way into an engineering Cadetship at Repco, commencing in January 1966 in the Richmond engine testing laboratory where the first Repco Brabham engines were designed, made and tested. Making and racing my own cars probably helped to get this placement because most Repco engineering cadets started in a factory environment.”

Among his earliest task as a cadet was making the shadow boards for the new machines Repco purchased for the manufacture of the racing engines. These were installed at the Maidstone factory where the whole operation was transferred during 1966, though we still ran the engines on the Richmond dynamometer while the new cells were constructed at Maidstone. Nigel was assigned to assist Michael Gasking, the head technician, with engine assembly and dynamometer running of the engines.

“It was such an exciting time. Remember, our Australian engines won two world drivers championships and two constructors championships. In their first two seasons. Unimaginable today.”

Fifty years later, Nigel bought the one-off BT17 Brabham only to discover, through his old handwritten notes and test details, that the Repco Brabham engine in it when it was first built was one he’d worked on. For the young engineer, it was an amazingly exciting time.

“Early in 1966, Gasking and I were running an early F1 3-litre engine with the Lucas metering unit in its revised location. Originally it was at the rear of the valley (between the cylinder banks) and driven by a cog belt from the back of one camshaft. Jack was leading the non-championship 1966 South African GP (on January 1) when it came adrift. He also set fastest lap, so we knew the potential was there. Phil Irving changed it so that it was located and driven from the rear of the chain casing. Problem solved.

“I was asked to work out how we could adjust the air/fuel mixture while the engine was running. I decided to make a little device that we could mount on the back of the metering unit. I had the idea of using a short piece of chain and two small sprockets. So I bought a Meccano chain and two Meccano sprockets. After a day or so I’d made the little contraption.

“I was the laughingstock of the place. Phil and my boss Frank Hallam were obviously amused, but too tactful to say much. Anyway, we fitted it up, ran the engine and it worked perfectly”.

“After the dynamometer running was transferred to the new Maidstone cells, I was back in Richmond on project engineering tasks. Sometime later the blokes there sheepishly admitted they were still using my “contraption” and it was working flawlessly.”

Nigel recalls a couple of “incidents” that occurred in the Richmond engine laboratory. He was then a project engineer working on product design, development, and testing.

“One night a couple of us were on the second shift, running an engine through a 200-hour wide open throttle test. We were upstairs having a coffee when there was a very loud bang. Then all went quiet. Rushing down to the dynamometer cell we could see flames. I rang the fire brigade, who had only to come from Richmond, and suggested they avoid parking next to the petrol bowser and over our 10,000-litre tank.

“They were there within minutes, parked next to the bowser.”

“The engine had stopped due to ignition failure. But why the fire?

“A connecting rod had gone through the side of the block and taken out the distributor. Ignition failure! Oil over the exposed exhaust pipe leading to the external muffler instantly created the fire.

“Two colleagues, sharing a car on the way to take over the night shift, followed a fire truck up Burnley Street. One said to the other, “wouldn’t it be funny if…” Yes, the truck was on the way to us.”

Today, at 79, Nigel looks back on a brilliant career and appreciates how fortunate he was to be professionally linked with so many talented people.

“It was an enormous privilege to have known and worked alongside Phil Irving, Peter Holinger, John Judd, the great Ron Tauranac, Michael Gasking, Don Halpin and, of course, my dear friends, Jack Brabham and Norman Wilson, and many other very clever people over those years.” says Nigel. “Phil’s working hours were a little ‘different’, he’d rarely appear until late morning, but would be at his drawing board well into the night or early morning. Every morning the biscuit tin was empty.

“One day he gave me a little drawing on a piece of paper the size of a postage stamp and asked if I’d make the object for him. I thought this was fantastic. I’m the cadet engineer and I’ve been asked to make some secret part for a new racing engine by the famous Phil Irving. After a day or so I’d made the part, gave it to him and asked him what it was for. “Oh, it’s to hold the exhaust on my Rover”.

From the time the BT19 was purchased by Repco from Jack Brabham (actually Jack Brabham Holdings) for $10,000 in 1977, it was effectively in Nigel’s area for coordination of its restoration and movement. It was used for promotional events and driven many times by Jack Brabham. Nigel also found himself behind the wheel as the “go-fer”, ferrying and positioning the car ready for Jack including once at the Goodwood Revival in a tribute event for Sir Jack. The BT19’s restoration was contracted out to Jim Shepherd, a talented racing car builder and restorer, while Don Halpin rebuilt the engine. Together with Bill Freame and others they got the whole thing together and working.

Nigel’s work broadened into the testing of the various engine parts made in the Repco engine division.

Nigel claims, “Incidentally the quad cam 860 series engine was undoubtedly the right way to go for the Formula One program, but it needed more development time. Perhaps if the 1967 single cam per bank engine been further refined for 1968 another championship would have resulted. Anyway Brabham took on the incredibly successful Ford DFV, and Repco started to wind down the engine project, though not for long since then came the F5000.

Nigel moved on to project engineering, heading up engine parts product engineering, and technical liaison with Repco’s overseas licensors. Ultimately, Nigel was appointed Chief Engineer of the Engine Division and Original Equipment Sales.

In 1986 Repco withdrew from engine parts manufacturing and sold the engine parts division to a management buyout of which Nigel was one of the nine senior executives. It was the largest management buyout of the era and the resulting Automotive Components Limited (ACL) employed 1000 people in Australia and even an operation in the USA. It was a friendly arrangement, with ACL continuing to make products for the motor industry and with a supply agreement to Repco. Nigel continued as chief engineer. The purchase included the championship Brabham BT19 and the Matich SR4, the latter had been transferred to Repco from its owners, Rothmans, in 1971.

Driven by Frank Matich, the SR4 won the 1969 Australian Sports Car Championship. Its incredible racing history reads: 19 starts, 19 pole positions, 15 wins, eight lap records and just one defeat (though it still came second, despite stopping to fix a throttle spring). The car, built in Sydney by Henry Nehrybecki, was intended for Frank Matich to take to the 1968 CanAm series but it raced only in Australia. Nigel says, “The SR4 totally dominated the class and led to the coining of the phrase ‘doing a Matich’ which is defined as taking pole, winning, taking the fastest lap and also the lap record.”

After a cosmetic restoration the SR4 was on display at the Birdwood National Motor Museum for many years and later the National Automobile Museum of Tasmania in Launceston. Eventually Nigel built up a 760 Series 5-litre Repco Brabham quad cam V8, one of perhaps only three or four, quad-cam Repco engines running. He has a complete and running spare, an ex Indy 4.2 litre quad cam Repco Brabham engine and also has the only quad-cam, diagonal port prototype Formula One engine, run, but never in a car.

Nigel managed the restoration and movements of the SR4 over the last few years of ACL’s ownership before he bought the car in 2005, the year he retired. At the same time Repco bought back the BT19 and asked Nigel to be caretaker.

Nigel began a full chassis restoration of the SR4 in 2006 and was not surprised to find Henry Nehrybecki’s craftsmanship was still evident in the quality of the frame: only one tube had to be replaced to improve the seat belt mountings to contemporary standards.

The SR4 was driven at the 2006 Speed on Tweed by John Bowe and in Nigel’s care the car is displayed and occasionally demonstrated at circuits around the country and even in New Zealand.

Nigel still skis, works out at a gym every day, and frequently drives his 1962 E-Type roadster. Having lost an eye due to picking up an eye infection while skiing in New Zealand, motor racing is now confined to regularity events and sprints. He owns the ex-Henry Nehrybecki/Bob Holden/Ian Pope Lolita Mk1, the Nehrybecki created Matich SR4 and the Brabham BT17, group 7 sports car and does all his own preparation and servicing at his factory over the road from Bill Hemming’s Elfin Centre “so there is always someone around to help”.

Today, Nigel’s daily drive is a Mercedes-Benz, a GLE 350 diesel fitted with the rare Country Package: sump guard, dual ratio gearbox, and ride-height adjustable suspension which has proved handy in snow or if fitting chains. The gearbox has numerous settings according to the terrain, also good if off road. “It’s a very good car, ideal for towing a big trailer and great for Mount Buller,” says Nigel.

And the GLE is also the perfect place to loudly enjoy Pink Floyd, Mick Jagger and Dire Straits. A musical inheritance.