by David Burrell

The Australian Motor Heritage Foundation is privileged to showcase some of the automotive design work of David Bentley, who worked in the design studios at British Motor Corporation Australia (BMCA) and its parent company, the British Motor Corporation (BMC), in the UK, during the 1960s.

In this five-part series, David will share many previously unseen BMC design proposals for the X6 Tasman and Kimberley, which he helped shape. These rare sketches and drawings are from David’s private collection and include a never built station wagon, five door hatchback and alternative grille ideas.

David’s design career began in 1960 at BMCA where he was an apprentice in their training program which included working in the design office, located next to BMCA’s styling studio. David told me that:

“It was a dream of mine to work in the styling studio. In 1963 Romand Rodbergh was the newly appointed head designer. He had been hired from Holden and I was selected to join him as his assistant.”

Back then, styling was not a high priority for BMCA nor BMC. Here’s what BMC’s technical director, Alec Issigonis, said about car styling in a 1964 New York Times story:

“I’ve always felt that stylists, such as you have in America, are ashamed of a car and are preoccupied with making it look like something else, like a submarine or an airship. As an engineer, I revolt against this.”

Unlike Ford and GMH, where styling was seen as a business-critical investment, BMCA’s low priority meant that its styling studio was very rudimentary. David Hardy, another former BMCA designer, told me that it:

“Didn’t look much different from a mechanical repairs garage. Just a concrete floor, stuff sort of lying around and a couple of car bodies in there.”

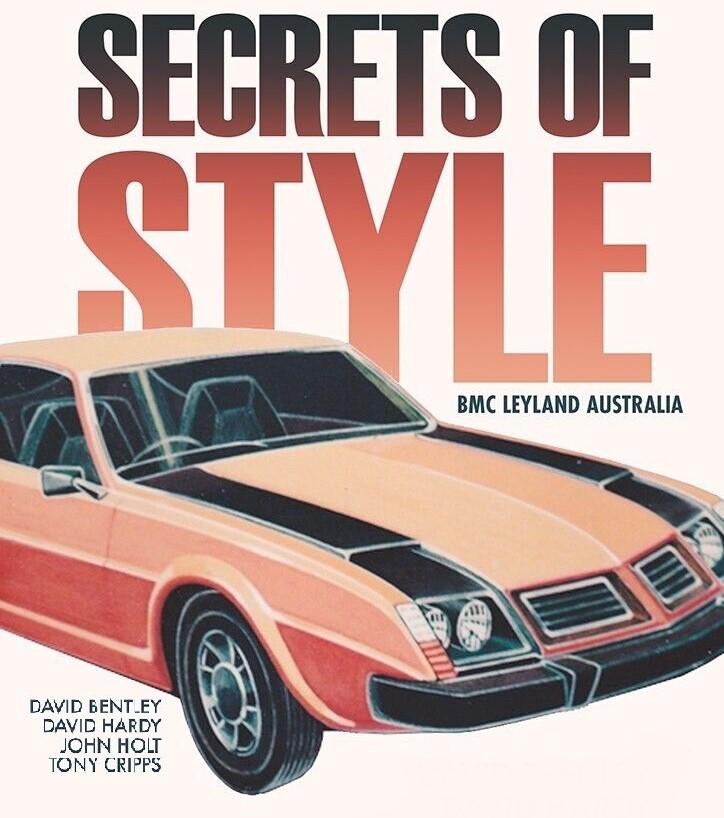

The styling staff were low down in the organisational hierarchy, reporting to a mid-level engineer. They did not participate in the decision-making committees that oversaw product planning, colour selection, trim, badges and upholstery for new and existing models. In the book The Secrets of Style, which David co-authored with David Hardy, Tony Cripps and John Holt, the authors revealed that one member of the colour selection committee was found to be colour blind. Commented David Hardy:

“They just didn’t think of it (styling) as anything except what you do at the end to dress it up.”

For Rodburgh, this dismissive attitude within BMCA (and BMC) about styling, was a continual challenge. Bentley and Hardy both recall that Rodbergh always championed the role of styling to the top executives, advocating its critical role in the early stages of vehicle/component development, largely to no avail.

David Bentley clearly recalls his first task when he arrived in the styling studio.

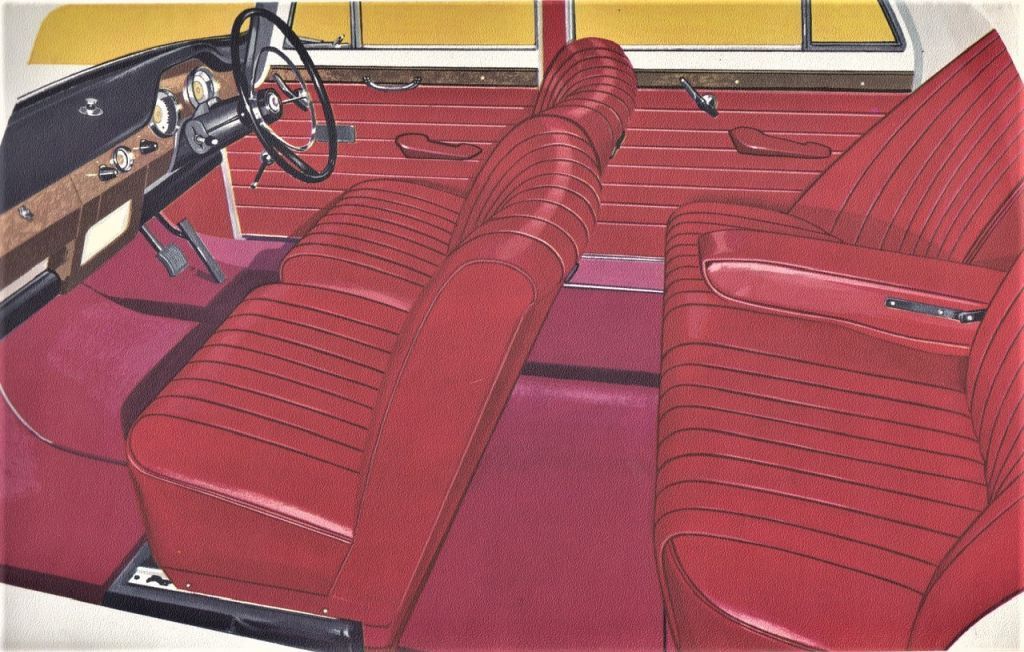

“Romand thought BMCA’s colours were drab. My first work was the seats and colour trim for the 1964 Wolseley 24/80 and to develop new exterior colours and new vinyl materials for interiors for other models.”

During 1965 Rodburgh advocated for the development of three and five door hatchbacks to eventually replace the Morris 1100. Rodbergh and Bentley created sketches and scale clay models of the concept. When shown to their engineering bosses they were told they had wasted their time.

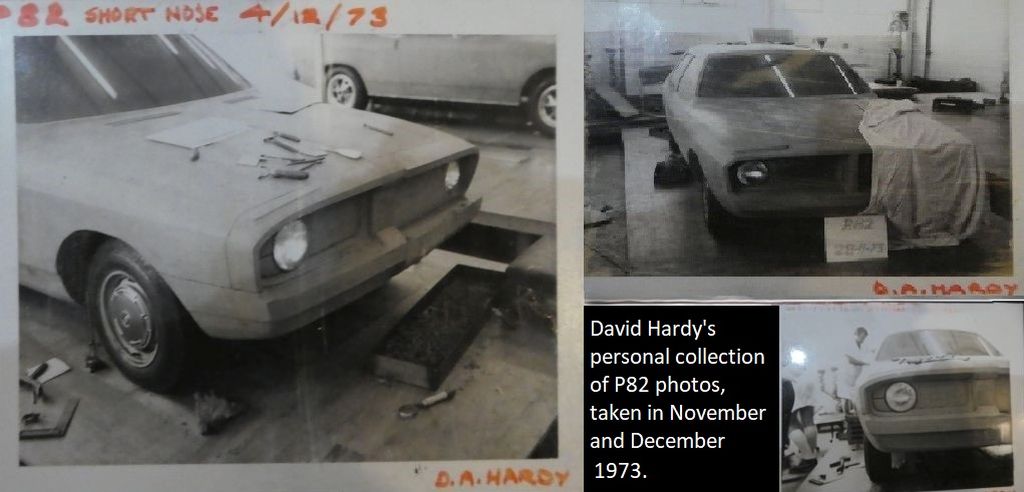

The hatchback idea later emerged as the 1969 Morris Nomad (which had been developed in the UK for BMCA) and the BMC’s Austin Maxi. It was also the foundation of a never released range of BMCA small cars, coded P82, that were planned to follow the P76.

Another rejected project was a considerably thicker steering wheel for the 1100, as part of a new facia design. David Bentley recalls that an engineer could not see the need for the thicker wheel, telling David that:

“Everyone steered the car with the spokes, not the rim.”

David also assisted in the design of the Austin 1800 ute, where he enabled the tailgate to be almost full width by rotating the Austin 1800’s horizontal taillights to vertical. It solved a problem the engineers had been pondering for weeks.

In 1966 David won a Rotary scholarship to study design at the Birmingham College of Art and Design. During this time, he worked at BMC UK’s Longbridge (Birmingham) design studios. BMC also had another design studio in the old Morris facility at Cowley, Oxford.

In mid-1968, while David was working on the Austin Maxi project at Longbridge, he was sent to Cowley where he was tasked with completing the Tasman and Kimberley. It was coded by BMCA as YDO13/19 and as the X6 in the media. The styling was being undertaken in the UK because BMCA’s design studio was too rudimentary. The project had been started by ex-Ford designer Harris Mann, who was now fully occupied with shaping the Morris Marina.

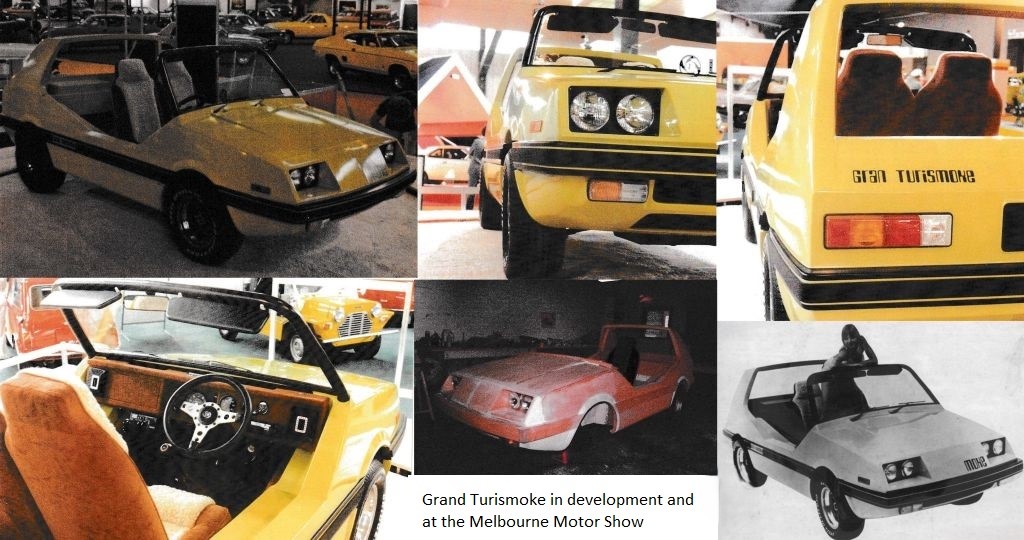

In late 1968 after completing the Tasman/Kimberley David returned to Australia. Not convinced there was a future career with BMCA he resigned and joined Carl Neilsen’s design consultancy. Later, he worked at Hunters Douglas designing aluminium furniture. David then established his own consultancy, where he had a long association with Jakab Industries developing specialist vehicles for the armed forces, ambulances and Australian Post. Together with model maker Stuart Phillips he developed after market body kits for Mazda, Alfa Romeo and Fiat. Leyland Australia commissioned him to design and build the Grand Turismoke concept car, based on a Mini Moke.

David also created sketches of the P76 for Wheels magazine in 1973, when then editor Peter Robinson, and AMHF director, asked him how the car could be made more appealing with minimal changes. In the early 1990s David transitioned to his other passion, boat design. His marine design consultancy is known worldwide.

In part two of this series, the early styling ideas for the X6 Tasman and Kimberley sedan are featured. Later instalments will showcase additional sedan proposals, the never built station wagon, five door hatchback and grille alternatives.

What these sketches and drawings also reveal is a glimpse of what an X6 range of cars in the 1970s might had been – a six-seater, six-cylinder, front wheel drive, family sized sedan, wagon and hatchback – had BMCA not chosen to developed the P76 sedan, wagon and Force 7 coupe. It raises the question: might the company’s fate been very different had the X6 path been chosen?

Note: Through out this series I will use BMC and BMCA to describe the British and Australian companies, respectively. This brings consistency and simplicity to the narrative during a time when the company was merged with Jaguar and Leyland and names kept changing.