Directly opposite my desk, sitting atop my model cabinet, is a voluptuous one-tenth scale clay model of an open sports car. It’s a daily reminder of a unique concept car about which on first sighting Giorgetto Giugiaro said, “it is not a car, it is a piece of art.”

This is the Focus before the Focus.

Ford’s 1992 Ghia Focus, a slice of rolling sculpture, did not make production, but its influence permeated Ford’s design studios – 1997 Puma and 2004 StreetKA – while the interior shapes and surfaces freed up the designers and helped inspire Ford’s ‘New Edge’ interiors. You could also argue that elements of its shapes and styling features inspired Chris Bangle’s 1994 Fiat Coupe and the 1993 Fiat Barchetta.

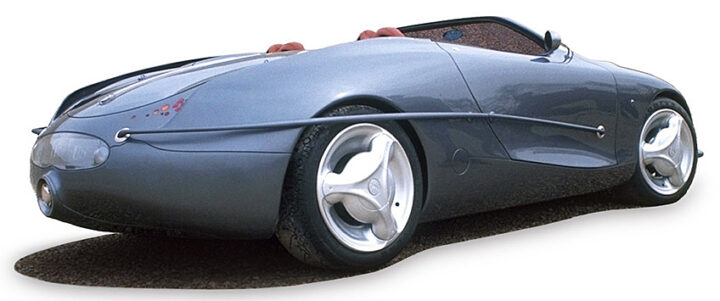

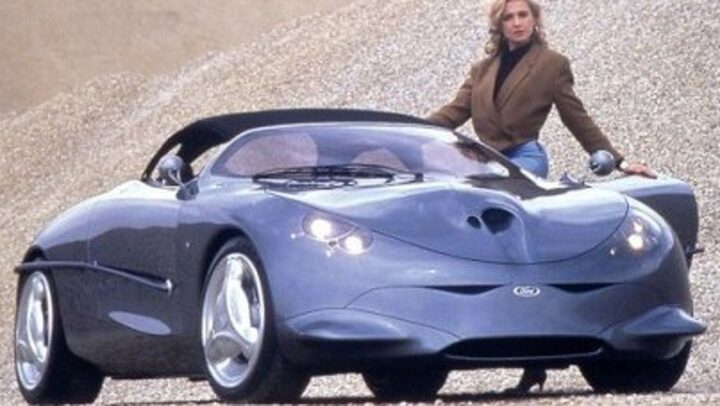

Designer Taru Lahti’s Focus is a complex, eclectic, and hugely imaginative symphony of shapes, textures, materials, and forms, subtly crafted; a masterpiece of creativity, at the same time both predictable and avantgarde. It teems with fascinating details that are never unpleasant or awkward. By any criteria, the Focus is an astounding piece of design.

How did such a startling concept car come about?

In June 1991, Ford’s senior management in Detroit directed Tom Scott, head of International Design Operations, to look at designing a new roadster for Europe and possibly America.

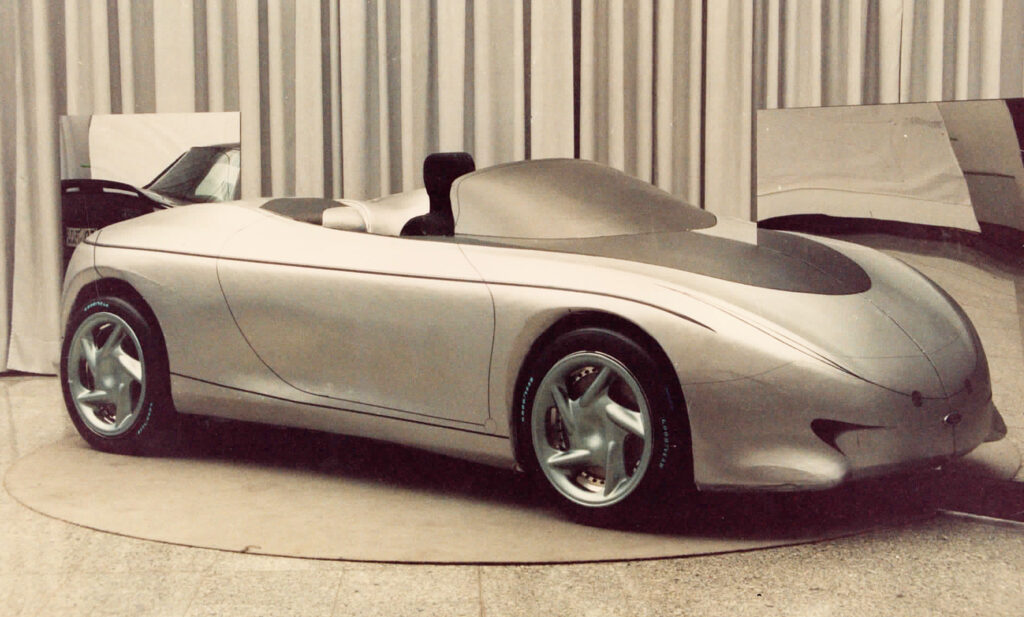

Seven different designers – three at Ghia, the remainder at Ford’s Dearborn, Cologne and Dunton studios – began working on themes for the sports car in August 1991. Ford hoped that by mixing cultures it would get a global view of where sports car design was heading in the next decade. The target was the 1992 Turin show’s design forum. The designers knew the show car was going to be built on a shortened Escort RS Cosworth platform, so it would be a fully functioning car offering an exciting opportunity, singularly rare within Ford.

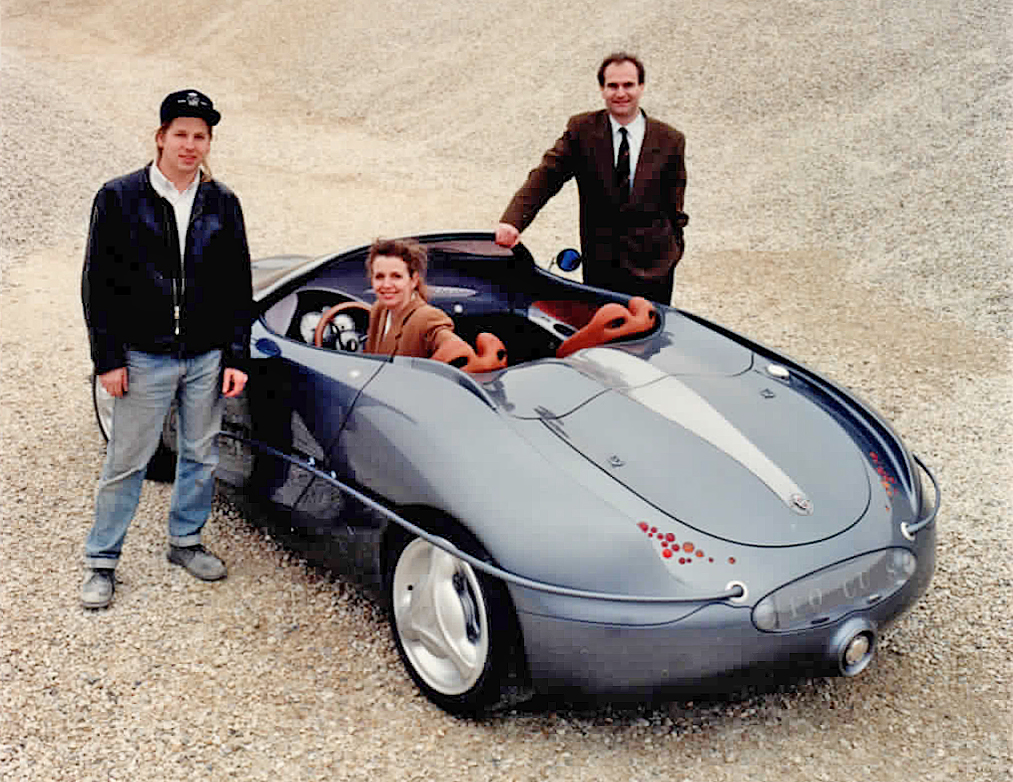

Taru Lahti, who already had the radical 1991 T-drive Ford Contour concept car in his portfolio, was given three weeks to come up with some ideas. Jack Telnack, Ford’s design boss, so liked the originality in the 24-year old’s sketches that on September 15, 1991, Lahti arrived in Italy to work at Ford’s Ghia studios. He was supposed to stay for three months.

In early 1992, when I first saw the Focus, Filippo Sapino, who ran the Ghia studios in Turin, explained, “We didn’t want just another sports car. Not a supercar but a compact, powerful roadster with real character. And we didn’t want to lose sight of the possibility that it could go into production.

“There were no real reference points, except perhaps the Corvette and the Cobra, for there aren’t too many rivals in the class we were considering. The Cobra was our thought starter because it has a confident, strong shape. We knew we didn’t need yet another sleek arrow-like wedge, but a muscular shape that puts a dress over the driver to make a nest.”

Lahti, working in one-tenth scale with his Swiss army knife, captured the essence of his voluptuous sketches in clay models, including the one in my office.

“Detractors say it’s playing with toys, but I like the way you can hold up a one-tenth model and turn it around, look at the plan view and side view to get a real idea of the proportions,” Lahti explained.

Each proposal was then blown up to a 40percent clay scale model on a computerised scan mill, while 40percent scale line drawings were used to check the packaging of the driver train and interior. During this process the front and rear overhangs were reduced. In a parallel development, the interior was done to scale, based on Ghia chief designer Claudio Messale’s design.

From here a full-scale model was built, with Lahti’s design on one side and Nico Tonello’s proposal on the other.

In October, during an intercontinental photo-phone conversation, Telnack, Scott and Graham Bell, the American designer in charge of cad-cam design at Ghia, choose Lahti’s design, the most daring of all seven proposals, to be built as Ghia’s concept car for the Turin show. Lahti stayed on at Ghia for another nine months.

Concept finally finished it was time to show the press:

“There’s not a straight line on this car: it’s almost as if there’s no front, no side and no back, just one organic form,” pony-tail swinging, an animated Lahti explained his creation.

“The Focus is a new language of shapes. I’ve taken forms from the human anatomy. It’s like skin over bones, the skin over the structure of the Achilles tendon. There are soft sections, but others are pulled tight to give tension to the whole car.”

Is it, I wondered, a piece of science fiction or some exotic fish with bizarre nostrils, tiny eyes, midget wings on its snout and scalloped fins on its duo-tone tail? From its asymmetrical air intakes to the circular exhaust pipe, that’s part of a spark arrestor in the centre of the tail, the Focus was a styling revolution.

In profile, the relationship of the cockpit with the rear wheels suggested the engine was amidships, because the rears were so far back, and there was so little front overhang. The body swelled behind the cockpit and then spilled down to the tail. The side panels were simple, to maintain interest in the top surfaces which merge into the cabin. The taillights and turn indicators a series of 14 tiny, different-sized circular lights on either side of the car.

Ghia wanted the interior to be a blend between the crudeness of a Ferrari F40 and the sterile Honda NSX. Sally Wilson Erickson, the British designer in charge of trim and colour at Ghia, insisted that Messale’s inventive design be finished in natural materials wherever possible.

Today, Sally, now chair of the College of Creative Studies Graduate Program in Colour, Materials Design in Detroit, remembers, “I don’t think any of us were ready for Taru’s highly innovative, disruptive approach to the appearance of vehicle exteriors, interiors and colour, materials and finish. Looking back, what we were doing at Ghia, in a collaborative, fast-paced-non-linear way reflects the disruptive culture of today’s start-ups.

“Led by Tom Scott, Taru and Claudio were let loose to design without boundaries (other than the package) resulting in a radically different form that looked like, in Taru words, “skin over bones”.

“I simply listened to Taru, who’s conviction came from influences in art, design and culture. My role was to listen to the designers and use colour, materials and finishes to express their concept. Choosing a neutral grey exterior is a good example. The colour’s job was to be as invisible as possible so that attention concentrated on the forms and details.”

“We wanted an F1 feel about the cockpit so that everything was close to the driver, with the richness of natural materials,” she said. Boat-like wood veneer covered the floor, various leathers for the brown and tan seats deliberately looked like saddles, hand beaten-polished steel flowed from the doors on to the top of the dashboard, down the console, across the hardtop’s hinged cover and spine-like down the centreline of the tail.

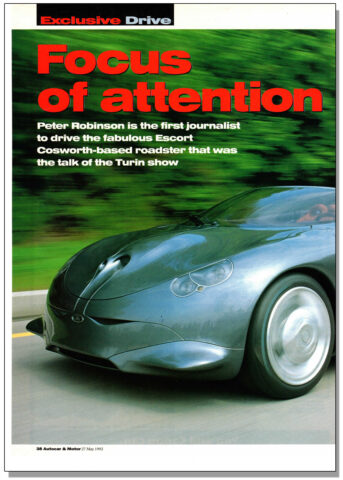

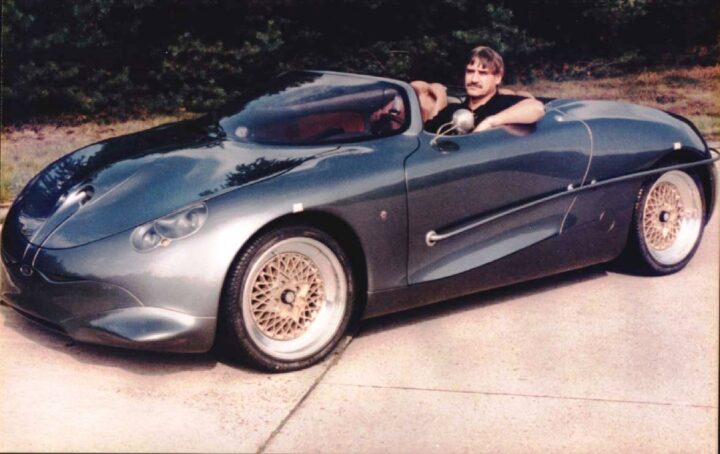

Just days after stealing the limelight at the Turin show, the Focus arrived on Turin’s Via Panoramica, a twisty piece of two-lane blacktop that’s so challenging motorbikes are banned. I was about to discover if the Focus was more than just a pretty face. Given the normal constraints of a one-off concept car, the Focus drove astonishingly well. Importantly, the structure felt rigid and durable. The Escort Cosworth underpinnings ensured quick, pin-sharp steering accuracy and real agility, so it came across as one of those desirable cars that reacts simultaneously to the driver’s thought processes. Even with the concept’s tired 220bhp Sierra-spec engine, the Focus felt quick, the gearchange lighter, shorter, and more precise than the Escort. What was also obvious, was the need for more suspension travel and suppleness. Yet, the driving still delivered sufficient pleasure to (almost) match Lahti’s fantastic shape.

Just days after stealing the limelight at the Turin show, the Focus arrived on Turin’s Via Panoramica, a twisty piece of two-lane blacktop that’s so challenging motorbikes are banned. I was about to discover if the Focus was more than just a pretty face. Given the normal constraints of a one-off concept car, the Focus drove astonishingly well. Importantly, the structure felt rigid and durable. The Escort Cosworth underpinnings ensured quick, pin-sharp steering accuracy and real agility, so it came across as one of those desirable cars that reacts simultaneously to the driver’s thought processes. Even with the concept’s tired 220bhp Sierra-spec engine, the Focus felt quick, the gearchange lighter, shorter, and more precise than the Escort. What was also obvious, was the need for more suspension travel and suppleness. Yet, the driving still delivered sufficient pleasure to (almost) match Lahti’s fantastic shape.

John Bull, Ford’s engineer at Karmann in Germany, was responsible for the Escort Cosworth and the vehicle dynamics on the Focus. It was Bull who sent an old Escort Prototype to Ghia to use as a base for the Focus project. Once finished, the car was sent back to Karmann. “It was not in a very drivable state, mainly because Ghia were not concerned about its drivability, only its appearance,” Bull says today.

Using Ford’s Lommel proving ground, Bull carried out basic suspension tuning. “The problem was Ghia had shortened the springs to give it the correct ‘showroom’ look. This meant it had no suspension travel. It looked great but rode horribly. I did the best I could to make it drivable.”

My too-short drive left the only question worth asking: how practical was the design, could it conceivably have been translated into production? In 1992, I was told Ghia designed the Focus to be perfectly feasible to build in quantities of between 1000 and 5000 per year. Bell claimed, “Focus is offered as a viable proposition for a low-volume operation. Fundamental decisions still have to be made but they don’t take a lot of time. We need to decide on the body material, then who would build it and where.”

The target price was 22,000 to 27,000 pounds (around $100,000 at the time): a Lotus Elan was cheaper, a Porsche 968 cabrio more expensive. At the time Ford had a contract to build 50000 Escort Cosworth, the mechanical basis of the Focus, so inevitably Karmann were favourites to build the roadster.

Today, George Manning, at the time Design Strategy Manager working for Scott, says, “We very briefly studied a limited production, but we just couldn’t get the investment low enough even as a low volume niche product.”

Tom Scott remembers, “Despite Ralph Lauren offering boatloads of money for the car, my immediate design and very senior management did not appreciate it at all.

“I’d gotten used to this kind of reception; slowly evolving design was the prudent way forward. I was looking to show that there was an alternative to the icy perfection of the mere stylist.

“The Focus was better appreciated in Europe – great magazine coverage – but no next steps.”

To John Bull’s knowledge there was no intent to produce a production version of the car, it was just a show car.

After completing the Focus, Taru travelled through Europe for three months before returning to Detroit and later New York, moving back to Detroit and Ford in late 1996. He returned to Tom Scott’s Advanced studio, started a deep dive into the youth culture, and then worked with Ford’s new studio in California, and never got back on a car program.

Finally, Lahti left Ford in 2001 to set up his own interior and industrial design consultancy, designing and fabricating one-off projects for individual clients and companies like MGM Grand Casino, Bedrock Detroit, Motorcity Casino and SmithGroup. Recently, with Adam Barry, he established Pull, a new industrial design company in Detroit.

Lahti does have regrets, “I may have done myself a disservice and missed an opportunity had I stayed at Ford. The New Edge aesthetic was fast approaching; I would have liked to see my take on ‘Edge’.”

In 2002 Ford sold 51 of its car collection, including many Ghia concepts, the money going to charity. The Focus went to an anonymous buyer for a staggering $(US)1,107,500. In 2020, when the Detroit Institute of Art was planning an automotive exhibition – “Detroit Style” https://www.dia.org/detroitstyle – it tried to find the Ghia Focus and contacted Christie’s, the auctioneers. However, the owner was not interested in loaning the car for what is a brilliant show.

How did I come by the Focus clay model? When Wilson Erickson left Ghia for Fiat in 1993, she was given the clay model as a going away present. Years later, when Sally lived in Detroit and worked at Ford, she asked me if I’d like the model. The precious clay sat on my lap during the plane journeys home.

PS: In a rare prescient moment, my original Focus drive story contained this: “Ford Focus: even the name sounds like it could go straight into the Ford line-up.”