Goodwood Motor Circuit, 2015

by Brian Goulding

I’ve been attending motor race meetings since 1955 – the first when I was four years old – but when I stopped working for the Australian Racing Drivers Club (ARDC) at the end of 2014 and effectively retired I still had one race meeting on my bucket list: the Goodwood Revival.

Created in 1998, the Goodwood Revival appeared to me to be the ultimate historic car race carnival – a place where you could see the best historic racing cars in the world being driven as they were designed to be driven.

My appetite was whetted by watching the meeting via live streaming from 2011. The quality of the cars racing and the intensity with which they were driven were amazing. Four years later I finally turned my dream into reality.

We – myself and Robyn, my wife – arrived at our B&B accommodation, just 10kms from the circuit, on the Thursday and drove to the Goodwood Motor Circuit on Friday morning to watch practice and qualifying. The following day, our B&B host showed us a back way along narrow B-roads, though I only just managed to keep up with his Ferrari.

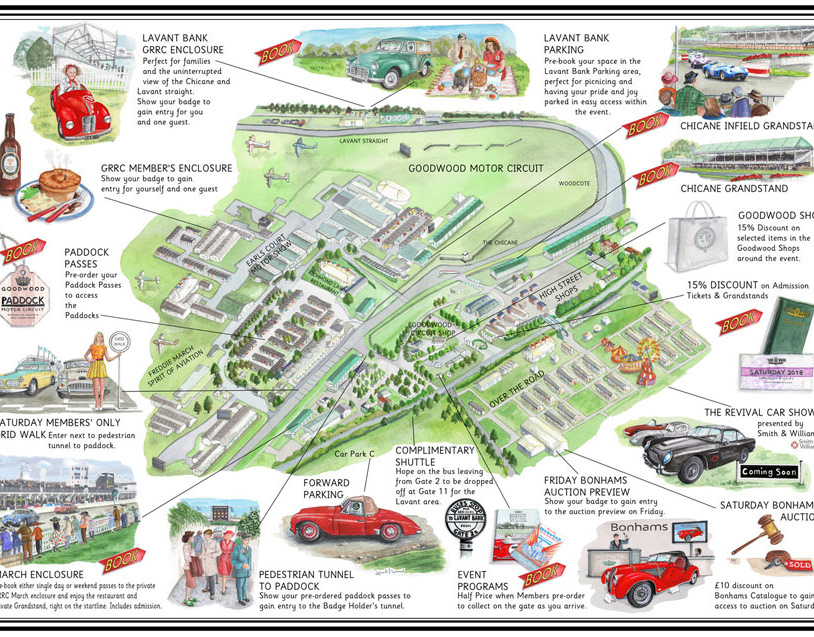

The Audi A6 rental car’s satnav guided us to a small roundabout near the main entrance and we were directed through a small farm gate into the parking area. Fortunately, we had “forward parking” passes in our package (bought online from the Goodwood website), so we were directed past general parking to the members and disabled area.

Walking through the carpark towards the circuit felt like a high-end classic car show. Apart from the expected sports cars and supercars, there were countless examples of veteran, vintage, hot rods, old commercials and classics, including three 1920s 3.0-litre Bentleys.

After a 200-metre walk we came to the Revival Fairground and merchandise marquees before having to show our paddock passes to cross a substantial footbridge over a public road. We then found ourselves in the Revival Market area which had its own high street, 1950’s Tesco supermarket, beauty parlour, barber and a fake old fashioned garage/repair shop selling automotive memorabilia and vintage clothing. Beyond this street were the backs of the Woodcote and Chicane Grandstands and the very special March Grandstand, reserved for guests of Lord March.

By lunchtime Friday there was a healthy crowd in attendance with 95 percent of the spectators in period costume or fancy dress. We met two blokes at lunch on Saturday who both had three outfits – one for each day of the meeting.

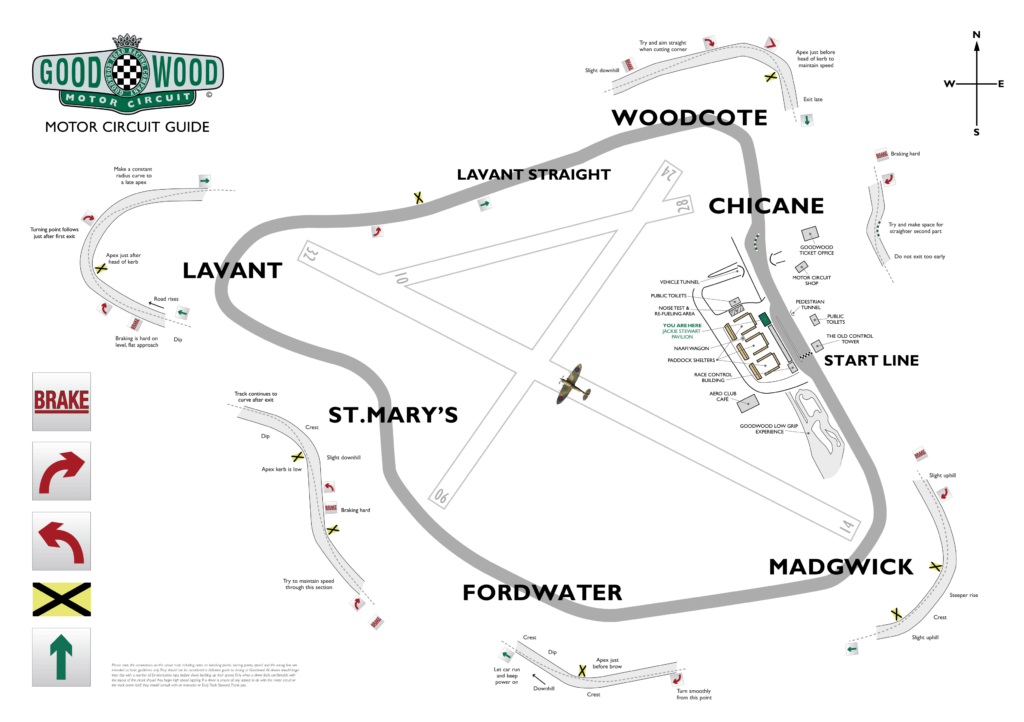

The circuit itself was beautifully presented. It had the look and feel of 1966, the year the circuit closed for open competition. The circuit, fast, narrow and quite bumpy, with the only concession to modern safety practices being the neatly tethered tyre bundles covered by modern cable belting. The major change is the addition of a chicane. The circuit opened in 1948 and followed the original airfield perimeter road, but was now considered too fast, so a chicane was added just before the start/finish line. Cars had to divert around a brick wall built out of real bricks. There is a classic photo of Jean Behra smashing into this wall in a BRM P25. He is shown half out of the car with great cracks in the bricks. The chicane lowered the average speed of the cars and sorted out the running order before the finish line. For the Revival, the chicane is now made of large Styrofoam blocks. The meeting was run by officials from the British Automobile Racing Club (BARC) plus 105 members of Lord March’s staff who were mentioned by name in the event programme. Yes, it is a big event.

Almost every grid was full to the maximum of 30 race cars. The quality of cars was unbelievable: Cunningham C4R, Bugatti Type 59, ERA E Type GP1, Ford Fairlane Thunderbolt, Ferrari 166 MM Barchetta, Bentley 4.5 litre Supercharged, Scarab – Offenhauser, Ferrari 250 GT SWB Breadvan, Shelby Cobra Daytona Coupe, Aston Martin Project 212 and Jaguar E2A. To name but a few.

Cars and drivers came from all over the world on a strictly by invitation-only basis, including a few Australians: David Brabham was driving an Isuzu Bellett in the pro–am touring car races with its English owner; Laurie Bennett raced the McLaren Chev M1B he keeps in England; John Bowe raced the Chevrolet Corvette Stingray C2 owned by Aussie Joe Calleja. The commentators called John Jack Bow.

Most drivers had one qualifying session on Friday and then one race on Saturday or Sunday. There seemed to be no noise restrictions with many cars running open exhausts. I had forgotten how annoying loud race cars are.

Every race started with a siting lap, after which the field was gridded up with the help of grid girls in tight jump suits (very 1960’s). The girls then left the grid and the cars were sent on a warmup lap. Once on the grid the cars were on the one-minute board and then 30 second board before the race was started by the dropping of the Union Jack. At the end of each race the cars cooled down for a lap. The first three place getters received a cigar and the drivers were interviewed on the grid. They then did a victory lap. Consequently each 25-minute race actually took 43 minutes to run. Nobody seemed to mind.

In total there were 14 different race categories, their races spread over Saturday and Sunday. One category had a race on both days using a pro-am format, with a Saturday race for celebrities and a Sunday race for the owners. A brief description of each category follows.

Freddie March Memorial Trophy – a 90-minute, two-driver race for cars that raced in the Goodwood Nine Hour Race held between 1952 and 1955. Held at dusk on the Friday night, the race finished in the dark without any track lighting.

Goodwood Trophy – a 20-minute race for Grand Prix and Voiturette (pre-war Formula Two) cars of the type which raced from 1930 to 1950.

Fordwater Trophy – a 20-minute race for Production Sports cars of a type raced between 1948 and 1954.

Barry Sheene Memorial Trophy – two 25-minute two-rider races for motorcycles of the sort that raced between 1962 and 1966, though my research revealed there was only one motorcycle race meeting at Goodwood between 1948 and 1966.

St. Mary’s Trophy – two 25-minute races for production-based saloon cars of a type that raced between 1960 and 1966.

Lavant Cup – a 20-minute race for drum-braked Ferrari sports prototypes of the 1950s. The conservative estimate of the value of the 26 cars on the grid for this category was 100 million pounds ($175m).

Brooklands Trophy – a 20-minute race for sports cars in the spirit of the great Brooklands endurance races prior to the circuit’s closure in 1939.

Whitsun Trophy – a 25-minute race for unlimited sports prototypes that raced up to 1966.

Earl of March Trophy – a 20-minute race for 500cc Formula Three cars of a type that raced between 1948 and 1959.

Richmond and Gordon Trophies – a 20-minute race for 2.5 litre Grand Prix cars that raced between 1954 and 1960.

RAC TT Celebration – a one-hour, two-driver race for closed GT cars in the spirit of the Royal Automobile Club Tourist Trophy races held between 1960 and 1964.

Glover Trophy – a 25-minute race for 1.5 litre Grand Prix cars of a type that raced between 1961 and 1965.

Sussex Trophy – a 25-minute race for World Championship sports cars and sports/racing cars of a style that raced between 1955 and 1960.

Setterington Cup – a two-part race along the starting grid for children under 12 (or was it 10?) in Austin J40 pedal cars. In my view a complete waste of valuable time.

At the bottom of each page in the Revival programme that showed the cars entered for each race was a quaint warning – “NOTE: Where betting takes place bookmakers will pay first past the post irrespective of objections.”

I noticed a fundamental difference in the way the cars are described in the programme. In Australia we describe a Lotus 24 powered by a Coventry Climax engine as a Lotus 24 Climax. At Goodwood this car was shown in the programme as a Lotus – Climax 24. Also, the year of construction for every car was shown in the programme, but no colours.

Because of my close connection with the Muscle Car Masters, I was especially interested in the two races for historic touring cars (1960 to 1966) and wanted to see how MCM and Goodwood compared. When looking at the entry list there were some obvious cars which could have come straight from Group Nb at the MCM: Morris Cooper Ss (seven) and six Mark 1 Lotus Cortinas. We’ve seen Ford Galaxies at the MCM and there were two at Goodwood, along with a couple of Alfa Romeo GTAs and a couple of 3.8 Litre Mark 2 Jaguars. There was also two reverse rear window Ford Anglia 105Es, one powered by a 1500 motor and the other a 1650 – both much bigger engines than Australian cars.

So much for similar cars. The more unusual cars competing were a Mercedes-Benz 300SE, an Isuzu Bellett, a Fiat 1500 Abarth and no less than five BMW 1800 TI/SAs. BMW built 200 special versions of the 1800 sedan between 1964 and 1965. The homologation special featured 150bhp, rear disc brakes and a five-speed gearbox. The current race versions were very competitive. The commentators refereed to them as “Teezas”.

By far the most unusual car on the grid was a 1964 Ford Fairlane Thunderbolt. I had not heard of this model before, but subsequent research revealed that Ford made 104 Thunderbolts in 1964 for use in American drag racing. The production car featured lightweight body panels, bonnet scoop, 427 high compression engine and larger crown wheel in the diff for better acceleration. It had all the power of a Galaxie in a much smaller and lighter package. I was disappointed there were no Mustangs and no Falcon Sprints competing.

How was the racing?

In the Saturday race Gordon Shedden and Andrew Jordan in Lotus Cortinas ran away with the lead, dragging Frank Stippler’s Alfa GTA with them in a three-way battle. While they swapped places at the front Tom Kristensen was scything through the field from a rear of grid in the Thunderbolt. Inevitably the mighty Ford caught the leading group and picked them off one by one. In the end Kristensen won by a second and a half, but it looked all too easy. On the cool down lap he opened the driver’s door and waved to the crowd while cornering on opposite lock. In the Sunday race Henry Mann, the owner of the Thunderbolt, won easily from grid Two. There was a fantastic battle between Alex Furiani (Alfa GTA) and the appropriately named Nick Swift (Mini Cooper S) for fifth and sixth. The Alfa eventually taking the honours by a car length plus a smidgeon.

Anyone who follows Australian historic racing knows that over the last 10 years the opportunity to see pre-1961 cars at race meetings has disappeared. As a result, I was really impressed by the Goodwood trophy and its grid of unbelievable quality, including including 10 ERAs, three Alfa Romeo Type Bs and a 308C, eight Maseratis, Frazer Nash Monopostos, a couple of Bugattis and a Talbot Lago. The race turned out to be a bit of an ERA benefit. Callum Lockie, on pole in his Maserati 6CM, made a slow start and was jumped by Nick Topliss who made a jack rabbit start from the second row. Topliss faded to be overtaken firstly by Mark Gilles (ERA) and then pole man Lockie (Maserati). Gilles went on to win at an average speed of 92.27mph – not bad for an 80-year-old car with skinny tyres and no suspension on a damp track. There was not one roll-over bar or shoulder strap to be seen on any of the cars.

On Sunday morning the 500cc Formula Three cars from 1948 to 1959 contested the Earl of March Trophy. The race was a four-car battle between three Cooper Nortons and a rarer Kieft Norton, similar to the car in which car Stirling Moss made his racing debut. Again, there was not a shoulder strap in sight, but there were a few roll over hoops. I speculated that nobody used seat belts because the front running Cooper drivers wedged their elbows on the side panels of the cockpit sides when cornering hard. On the run to the flag the second placed car, driven by George Shackleton, ran onto the grass verge. He slid back onto the track but over corrected and crashed heavily nose first into the concrete barrier opposite the pit lane wall. With no seat belts his face hit the nose cone in front of the small windshield but he immediately jumped out of the car and over the wall apparently unhurt. The winner averaged over 71mph…from only 500cc.

In addition to the racing programme there were lots of tributes and anniversary celebrations. It was just over 50 years (April 19, 1965) since Jim Clark and Jackie Stewart jointly set the last Goodwood outright lap record in the Sunday Mirror International Trophy for Formula One cars. Clark drove a Team Lotus Lotus 25 Climax while Stewart used a BRM P261 from the Owen Racing Organisation. Their shared time was 1 minute 20.4 seconds which was an average speed of 107.46mph. In the re-enactment Jackie donned his old tartan helmet to drive the actual BRM from 1965 and Dario Franchitti used a dark blue helmet with white peak (Clark’s colours) when he drove the Lotus around the circuit with Stewart.

Each day there was a moving tribute to Bruce McLaren who was killed while testing at the then de-commissioned Goodwood circuit in 1970. Twenty-eight of the most significant cars from Bruce’s career took to the circuit on all three days. They ranged from the Lotus 15 he drove at Goodwood in 1958 through Cooper racing cars, Ford GT40s to McLaren Can Am and Formula One cars. His personal road car, the road legal McLaren M6GT, was driven in the demonstrations by his daughter Amanda.

On all three days all six Shelby Daytona Coupes were paraded on the circuit and then displayed on the starting grid in front of their proud designer, American Peter Brock. Only six Shelby Coupes were built between 1964 and 1965 and this was the first time ever that they have been seen together. Their top speed on the Le Mans Mulsanne Straight was 20mph faster than the mechanically identical Cobra roadsters. They won the FIA World GT Championship in 1965.

To mark the end of production of the Land Rover Defender in 2015 there were parades of 45 weird and wacky Land Rover prototypes. They came from all over the world and were built for every type of application between the years 1948 and 1966 – the Goodwood circuit years. There was a demonstration of drag racing “gasser” cars which became popular after the introduction of drag racing to Britain in 1964.

The aviation component of the meeting was brilliant and all in all a very fitting acknowledgement of the 75th anniversary of the Battle of Britain. I have a personal connection to these aircraft as my father worked on Spitfires and Hurricanes while he was in the Fleet Air Arm before being sent to Australia in 1943.

When we arrived at the circuit, we naturally noted the grass airstrip on the infield but soon realised that when planes were taking off or landing the spectator mounds beneath the flight path had to be cleared by officials. Also, the aerobatics were limited because a 1958 Hawker Hurricane crashed onto a freeway just down the road two weeks prior.

During the war the little aerodrome, which would later become the Goodwood Motor Circuit, was known as RAF Westhampnett. It was the training and emergency strip for RAF Tangmire which was two miles to the east and centre of the Tangmire sector. Fifty-seven pilots from the Tangmire sector lost their lives in the Battle of Britain while 18 pilots made their last take off from RAF Westhampnett.

In a moving ceremony on Sunday local Air League cadets lowered the national flags of the 57 pilots as their names were read over the public address system. Most flags were Union Jacks of course, but there were a couple of South African, a couple of American, a couple of Polish, a Belgian and one Australian. The Australian flag was lowered when the name of Lieutenant Richard Renoff was announced. A lone grenadier guard stood on the top of the control tower and played the last post as four Spitfires from the Battle of Britain Memorial Flight flew above the circuit.

Two Battle of Britain veteran pilots, now in their nineties, were paraded around the circuit in a restored Humber staff car followed by 15 WW2 Jeeps carrying a mixture of WW2 veterans from various services. They received a standing ovation from everyone in the crowd – and why wouldn’t they?

Later 11 Spitfires and a lone Hurricane flew over the circuit in three lines of four formation. They were limited to large loops at low altitude but the spectacle and especially the noise was truly spectacular. The general feeling was that it will never happen again.

Without doubt this was the best race meeting I have ever attended. They say the crowd totalled 150,000 over three days, yet it never felt crowded and there always seemed to be room for more spectators. Yes, it was quite expensive. The cost of our package was 915 pounds per person which at the time equated to $2033 per person. As I write this in October 2016 the Australian dollar equivalent is a more reasonable $1533. That is expensive, but it is hard to think of a better way to spend the money.

‘Goodwood Goulding’ photos taken by Robyn Goulding