This story begins on Tuesday, March 4, 1969 in Holden’s Technical Centre, Fishermen’s Bend. And finishes almost 43-years later at Holden’s Lang Lang proving ground. As one of 31 press invitees to that Melbourne motor show eve preview of Holden’s top-secret Hurricane, I never anticipated driving the one-off dream car. At the time I wrote, “It is doubtful if anybody outside GMH will ever get to drive the car…”

Yet, for a few brief minutes on the Lang Lang skidpan, that is exactly what I did on January 25, 2012.

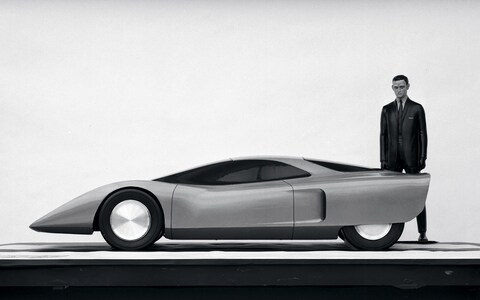

Today it’s almost impossible to convey the shock, the sense of awe, created by the Hurricane. Nobody had seen anything like its radical dart-like profile before. Holden, as a car maker was not yet 21-years old, even so its first concept car beat the comparably shaped Mercedes C111 by six months and the Lancia Stratos Zero by over a year.

So extreme was the Hurricane that nobody inside or outside Holden predicted a production future for the spaceship car that grabbed the front page of most of Australia’s newspapers. It was clear from my first sighting that there was never an intention to build the Hurricane, yet the one-off concept did provide a clear window to the future. Most obviously in previewing Holden’s own 253 cubic inch (4.2-litre) V8 that arrived in the HT Kingswood and Premier a few months later (and stayed in service until 1984, though the 308 cubic inch (5.0-litre) version survived until 2000). There was more: science fiction-like technology included on-board navigation, a rear-mounted camera as a substitute for no rear window, automatic air conditioning, digital instruments, oil–cooled front disc brakes, tilt steering column, adjustable pedals and, most dramatically, no door.

Instead, the designers came up with an hydraulic opening one-piece clamshell roof canopy, to ease ingress and egress and overcome the Hurricane’s incredibly low stance. It was surely no coincidence that at a knee-high 39.2inches, the Hurricane managed to undercut Ford’s GT40 Le Mans hero.

The Hurricane was the first public evidence of creative cleverness from Holden’s Research & Development group (hence the RD-001 codename). Bill Steinhagen, the ambitious American chief engineer, established the R&D department in 1965 and was keen to expand Holden’s engineering capability, especially in the face of a resurgent Ford Australia, and design expertise. At the same time, Holden’s marketing group was eager to build the brand image and, specifically, to generate advance publicity to showcase the new V8 engines then under development. Impressed by the ink an imported Camaro show car generated in 1968, Marketing and Engineering saw an opportunity to create a Holden concept car. According to an SAE Journal technical report, the Hurricane was seen as, “a project to design and construct a vehicle to explore more fully the complete spectrum of vehicle dynamics, stability, control and safety.”

Bern Ambor, Steinhagen’s 1968 successor, was also intent on energizing the engineers beyond Holden’s staid family car imagine. A scale model of what became the Hurricane arrived in Australia in late 1968, the mid-engine layout apparently decided by GM’s designers in Detroit. In an era of Can-Am racers, Ford GT40, Lamborghini Miura and Dino 206/246, the mid-engine layout ensured cutting edge credibility for a V8 sports car. The Hurricane’s striking proportions, there is virtually no rear overhang, and tight dimensions – try 4094mm long, 2438mm wheelbase, 1.803mn wide – mean it is almost race-car small.

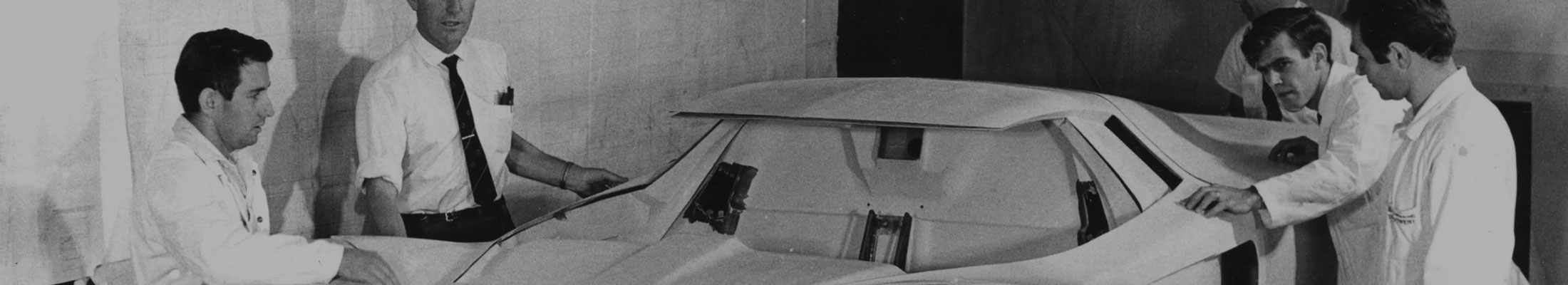

Designer Don DaHarsh developed the American scale model to full-size and with Ambor, former aeronautical engineer Ed Taylor and body engineer Jack Hutson, the team clothed the steel spaceframe in an epoxy-resin body. The small overhead valve Holden V8, mounted longitudinally, ahead of the rear axle line, featured an external cam drive and solid lifter cam and a Quadra-Jet Rochester carburettor, to make 260 (Gross) bhp (194kW) at 6000rpm and 260lb. ft. (353Nm) of torque at 3800rpm, rather more than the production engine’s 185bhp (138kW). The front suspension, fabricated by hand, was adjustable short/long arm with coil springs, while most of the rear suspension was borrowed from the C2 Corvette with the transverse leaf spring replaced by coils and dampers. GM’s American parts bin also donated the 1961-1963 Pontiac Tempest four-speed transaxle, the bell-housing adapted to the Holden block. The recirculating steering featured a slow 24:1 ratio while the front brakes were a wet design, based on system being used on Detroit’s public buses.

The Hurricane’s exceptionally low stance meant conventional doors, even gullwing doors, were never going to work. However, the American scale model only shows conventional door shutlines. As the one-piece hydraulic roof canopy, with its massive wrap around plexiglass windscreen without pillars and windscreen wipers, opens it simultaneously (electrically) raises the fixed seats. Nobody is sure who came up with this idea, but designer Leo Pruneau (who went to Holden design in 1969) remembers a small, three-wheeler GM concept car from the same era used a similar canopy. A search of GM concepts shows that XP800, in development through 1968 (though it was launched to the public as the Chevrolet Astro 111 Concept in 1969) used a near identical canopy door. From this distance, it’s impossible to know if the system was invented for Holden or Chevrolet concepts, more probably it was simultaneously developed for both.

Four decades after the Hurricane’s debut, nobody was sure if the car ever ran under its own power. Some former Holden employees believed the images of the car moving at the Proving Ground were only taken at a slow shutter speed, after the car had been pushed. To the delight of those involved in saving the Hurricane, Holden contacted DaHarsh during the restoration. DaHarsh quickly produced his own ancient Super 8 movie footage of the car being driven at Lang Lang.

After various motor show appearances through 1969 (and completion of wind tunnel testing) the Hurricane was loaned to various dealers, until the windscreen cracked. It was then stuffed away in the wooden crate that was used to transport it around the country and stored in a Holden Service garage. Around 1985-86 repairs, which included stripping and repainting the body, were finally carried out. In 1990-91 Holden first-year apprentices ‘restored’ the car. From then, until 2005 when Holden decided to properly rebuild the car, the Hurricane was on show at the privately owned Holden National Motor Museum in Echuca, Victoria and later at the Powerhouse Museum in Sydney in an exhibition entitled Cars and Culture. Twice, between the early ‘70s and 2000, the Hurricane was threatened with destruction. When Leo Pruneau discovered that chief engineer George Roberts had order that it be ‘cut up” he rescued it and deliberately hid it (in design’s workshop) from Roberts. Later, it was saved from Holden’s apprentice school students who were about to scrap it because they perceived the Hurricane was no longer of any use.

Various GM executives played a role in the Hurricane’s revival. Ed Welburn, then global head of GM design, noticed the car – it was getting a coat of primer – in early 2006 on one of his many visits to the Holden studios.

“I was so excited and immediately asked if it was the Hurricane,” Welburn explained to me at the Detroit show a decade ago, “As an 18-year-old at Howard University (Washington, DC), I saw a photograph of the car. It was one of the inspirations that led me to car design.

“When I realised what it was, I told the guys, we’ve got to restore it. I saw it the last time I was down there, they’ve done a great job.”

Mike Simcoe, now General Motors design boss, says Welburn’s help was crucial to getting the ground-up restoration off the ground. The other executive who was prepared to help fund the return to perfection was Mark Ruess, then CEO of Holden, and now President of GM.

In 2006, the car was turned over to Paul Clarke, manager for creative hard modelling at Holden – at the time one of just three GM divisions capable of building concept cars – while recently retired chief engineer Rick Martin reconstructed the Hurricane from archival photographs, technical drawings and the anecdotes of many people originally responsible for building the car, including designer Don DaHarsh who significantly modified the scale model sent from Detroit.

“It’s amazing what comes out of the woodwork,” says Clarke. “Guys in engineering would come in and go ‘my dad worked on that car’ and when you question them, they give you another lead to follow up.”

The car was in very poor condition, and so many parts had been pilfered over the years, that the restoration was almost like starting again. The body was breaking down, the original 253 engine was missing, as were the wheel trims and arms for raising the canopy. Interior gauges, the steering wheel, the rear-view camera, even the reservoir for the oil-filled brakes were gone. Much of the car was simply recreated, without adopting modern technologies, although the body was rebuilt using a more durable polyester resin, then repainted something close to the original metal-flake orange. The bespoke interior was recreated, the original seats were strengthened and re-trimmed, but most of the parts had to be built from scratch. Clarke is justifiably proud of his team’s efforts in restoring Holden’s first concept car.

My too short drive of the Hurricane took place in 2012 on the skid pan at Holden’s Lang Lang providing ground, in company with former Holden design boss Leo Pruneau. Driving the Hurricane involves climbing over the sills and dropping down on to the raised seat, the canopy is so well forward that there is a deceptive impression of space. Not when the seat is lowered and the roof and steering wheel begin their slow descent. It’s like being gradually jammed into a compression torture chamber. Head pressed hard against the roof, feet squished against the pedals, my contorted left leg can just engage the clutch. The Hurricane moves off, slowly. Up to second and gradually accelerating to around 30mph, you notice the leisurely yet still heavy steering. Every movement is deliberate, measured. Drive? Not in any contemporary sense, more like guiding a very rare and ancient machine, just to say you’ve done so. Even if it took 43-years.