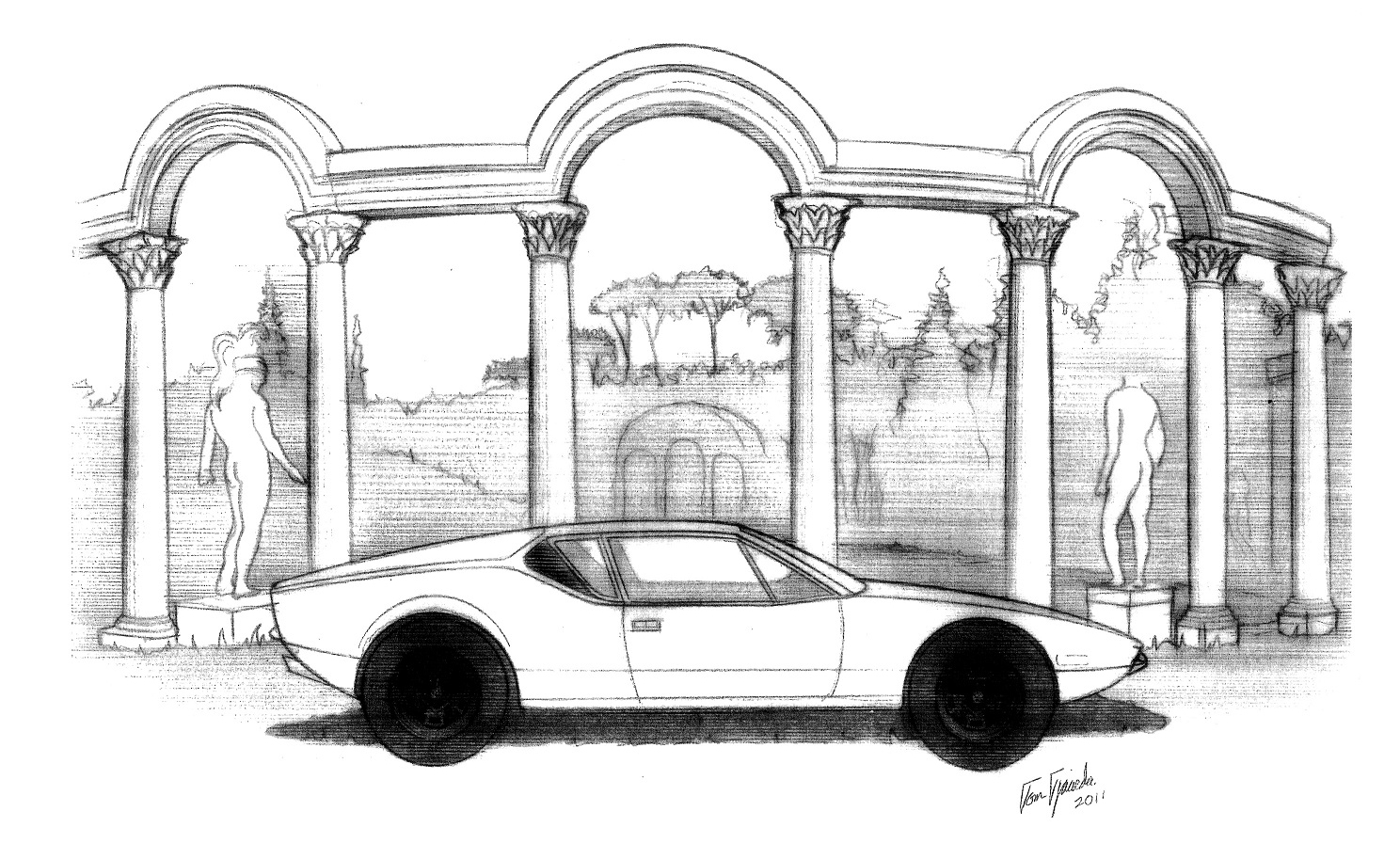

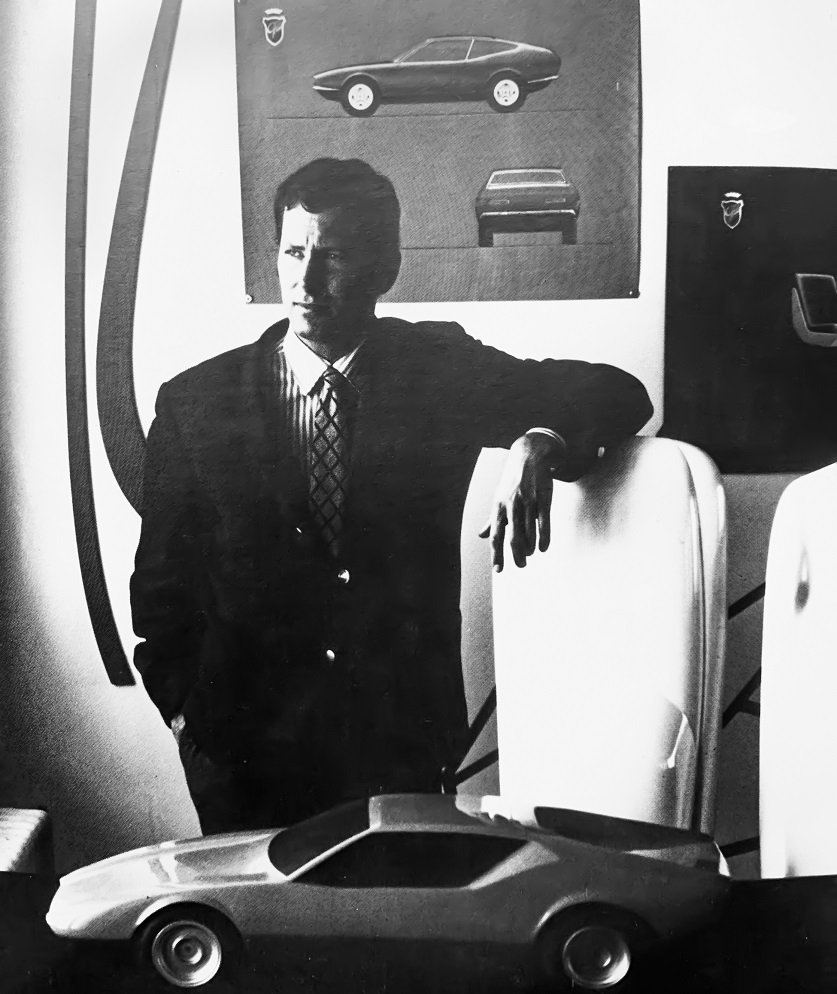

By the end of the 1960s, after a decade of designing cars for Ghia, Pininfarina, and then Ghia once again, the American architect-turned-car-designer Tom Tjaarda had finally developed a style and form structure which was distinctively his own. Cars like the Serenissima GT, the De Tomaso, Mustela, and the Lancia Fulvia HF Competizione and Marica were superb examples of pure forms, clean lines, minimal ornamentation, and subtle surfacing, whilst respecting the paradigms of proportions.

Two other projects for Ghia’s Japanese client Isuzu also showcased Tjaarda’s emerging style and his penchant for sharp-edged wedgy profiles: the Isuzu Bellett MX1600 was a striking midship sports car which set the tone for what would become one of the most important designs by the American. The De Tomaso Pantera, unveiled in March 1970, was the project that would not only bring fame to Tom Tjaarda but also make him a star and a hero to many automotive enthusiasts across the globe.

To understand the project better though it is worth stepping back a few years. With the unveiling of the Lamborghini Miura at the Geneva Motor Show on March 10, 1966, the concept of a high-performance supercar changed altogether. Until then the most powerful street legal cars had their engines at the front, driving the wheels at the rear. With the Miura, the practices and concepts tested in racing found their way to a car meant for providing high-speed transport across continents.

The Miura was not the first street legal car with its engine amidships; the credit for that would be the René Bonnet Djet, which became the Matra Djet, and was unveiled four years before. The Miura, however, was the first “full-house” mid-engine supercar. It would take arch-rival Ferrari another seven years to come up with a direct response (discounting the junior league Dino 206 GT, from 1967), but others, such as upstart Argentinian carmaker De Tomaso would be much quicker off the ground.

In fact, it was Alejandro de Tomaso, who was more of a pioneer, in launching his first mid-ship car, the Vallelunga, in 1964, followed by the Pampero concept in 1966. It was also in 1966 when de Tomaso unveiled the Mangusta, the first true riposte to the Miura, at the Turin Motor Show, barely eight months after the new supercar from Lamborghini had wowed visitors at Geneva.

The De Tomaso Mangusta was no less startling and was one of the finest designs by the 28-years-young Giorgetto Giugiaro, when working for Ghia. Powered by a 4728cc (289 cubic inches) V8 from Ford, developing around 306bhp, the car looked fabulous. With a claimed top speed of over 250 km/h, the Mangusta was more than a contender for supercar status.

Thus, when Ford was looking for a flagship supercar to counter the reputation that the Chevrolet Corvette Sting Ray had built up, the De Tomaso Mangusta looked like a good opportunity. After burning its fingers with the AC Cobra and the not-so-civilized GT40 misadventure with Carroll Shelby, Ford was keener on an Italian connection that could be a more than valid rival to Ferrari, which Ford had been thwarted from acquiring. In the meantime, Italian-born Christina Ford, the second wife of Henry Ford II, had acquired a Maserati Ghibli, a car that she found exquisitely beautiful and a delight to drive.

Lee Iacocca, the other Italian-born senior executive in close contact with Henry Ford II, had always had a soft spot for automobiles from Italy. Between the two of them, they managed to convince Henry Ford to look at acquiring an Italian marque and developing a range of models at the top end of the market that would be Italo-American in essence and spirit. Ford dispatched two experienced engineers Ray Geddes and Larry Kasanowski to take a close look at the Mangusta.

Unfortunately, it turned out to be disappointing. The dynamics and quality of the interior were abysmal, and the car had too many issues. Geddes and Kasanowski reported that the car was a complete disaster, and that it would make better sense to develop a brand-new car altogether. Alejandro de Tomaso gave Tjaarda the assignment, with the chassis specifications to be executed by Giampaolo Dallara, the brilliant engineer who had designed the chassis and the mechanicals of the Lamborghini. De Tomaso had lured Dallara to his company with the promise of going racing.

For Tjaarda, this new supercar was not his first with the engine located ahead of the rear axle, and with the masses altered considerably. He had cut his teeth on the Serenissima Ghia GT the previous year. Though the overall form language of the Serenissima was beautiful with perfectly balanced proportions, there were no details indicating the location of the motive power.

Tjaarda was keen to establish his own style and leave his imprint as a designer of note. “At Pininfarina, we had to follow the house style and our designs were gradual evolutions of cars done earlier by others. The house style was an overriding factor. When I came back to Ghia, Giugiaro had sort of established a house style too. At the beginning, I followed that. But as Alejandro de Tomaso did not care for such things, I was keen to produce cars my way, different from the style at Pininfarina, or by Giugiaro.”

Some of that can be seen in Tjaarda’s two projects completed in late 1968 and early 1969, the De Tomaso Mustela and the Isuzu Sport Wagon, and the private project that Tom Tjaarda was involved in with Peter Giacobbi. No doubt, influenced by his years in Pininfarina, Tjaarda was also embarking on his “variations on a theme.”

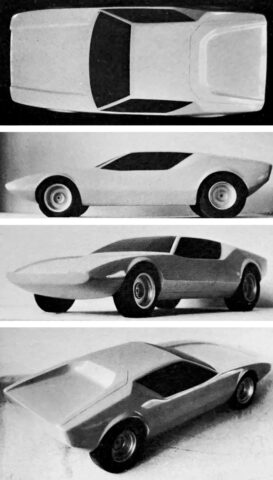

Two of the scale models had prominent swage lines that flowed and undulated over the rear wheel fenders, somewhat similar in style to the later AMC AMX and then the AMX/3 concepts (Ford was well aware that both AMC and Chevrolet were working on high-performance mid-engine sports cars, and it was important to beat them to the market.)

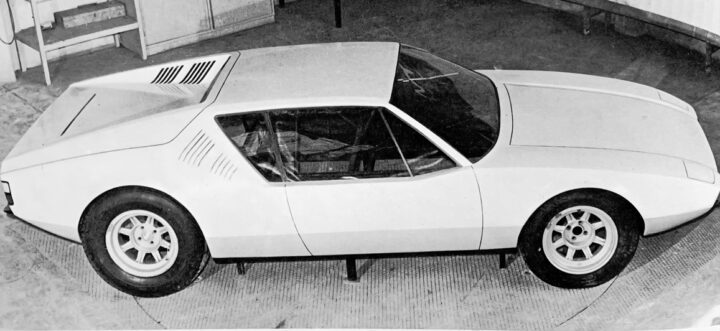

It was the third model, which featured a more wedge-like front complemented by muscular haunches that caught the eyes of the two Ford executives and Alejandro de Tomaso. This was rapidly transformed into a full-size fiberglass mock-up, which was ready by August 1969. “I met Lee Iacocca only once, when he made a surprise visit to Ghia to approve the Pantera,” recounted Tjaarda. “We had worked day and night to finish the styling model and when he came to see it the paint was still sticky. Alejandro de Tomaso had been away for two months and was calling every day to see how the model was coming along. Iacocca was shocked to see that a guy from Detroit had designed this ‘Italian sports car’ but he got over that quickly.”

“It took Iacocca about ten minutes to approve the Pantera design. He was practical, quick and to the point. It was obvious that he did not like to waste time in small talk. His visit coincided with an Italian holiday, and our favourite restaurant was shut, but a call from de Tomaso persuaded them to open their doors for the occasion. Iacocca was impressed with everything that we had done in such a short time, and we noticed that once he settled down for lunch, he became much more relaxed and entertaining. He loved Italy, felt his Italian heritage, even with a calculated hint of the mafia that could sometimes scare people.”

With the design and development of the new supercar going well, Ford took an 84 percent majority stake in De Tomaso on September 9, 1969. Tom Tjaarda had an insider point of view on the project, “When Alejandro de Tomaso realized that Lancia would not become part of Ford he had to come up with a new approach. So, along with his friend Lee Iacocca, they created the Pantera project as a promotional tool to entice customers to visit the Lincoln/ Mercury showrooms that were down on sales.

“The Pantera sports car was designed, engineered and made ready for production in only nine months. This was possible because of Giampaolo Dallara, for the excellent layout of the car and Venanzio Di Biase for working day and night to organize the production facilities at the Vignale plant, which had been bought by Ghia for the purpose of producing the Pantera.” Venanzio Di Biase was another person involved with the development of the Lamborghini Miura who de Tomaso had poached from Carrozzeria Bertone to help with the rapid development of the new supercar. Giampaolo Dallara, in the meantime, produced a monocoque chassis/body unit with a torsional rigidity some 70 percent greater than that of the Mangusta’s.

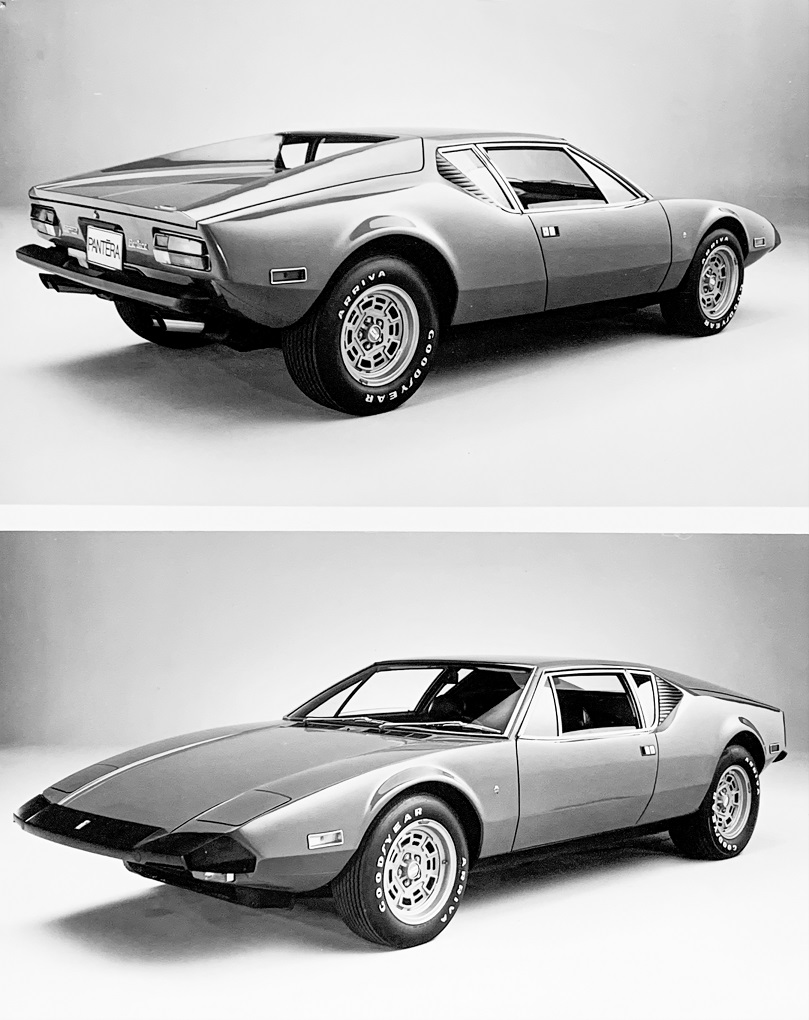

Powering the car was Ford’s 351 cubic inch (5763cc) Cleveland V8 engine, with drive going through a ZF-sourced five-speed gearbox to the rear wheels, promising 310bhp from a V8, a zero to 100 km/h time of 5.5 seconds and a top speed of over 155mph (250 km/h).

The version that made it to the US market sported molded bumpers which were designed by Christopher Dowdey – Branko Radovinovic Archives.The car, badged the Pantera (‘panther’ in Italian), was unveiled to the press in March 1970, at the Monza racing circuit, followed a few weeks later by its official public launch on April 4, at the New York Motor Show, where the bright yellow car was well-received. Both the press and the visitors to the show found it exciting and attractive and the specifications promised a “lot of car” for the suggested price of US$9,000, which was significantly less than half that of the Lamborghini Miura and the Ferrari 365 GTB/4 Daytona, the two supercars ruling the roost at the time.

With its dramatic body style, Ford seemed to have a winner in the Pantera. Plans were made to produce as many as 5,000 cars per year for the North American market alone, to be distributed by Ford through its Lincoln-Mercury dealer network, with Alejandro de Tomaso retaining the rights to sell the car elsewhere in the world.

The best-laid plans of mice and men though can and do go awry, which is what happened with the Pantera. The first problem was with the crash test, “with the front pair of wheels pushed all the way back to the seats!” remembered Tjaarda. “Dallara designed a pair of longerons, and this issue was solved.”

Initial quality and teething issues cropped up, along with problems associated with starting the series production. As the homologation of the Pantera for the North American market was taking time, sales began in Europe, with 285 delivered in Italy and the United Kingdom in 1970. Sales in the United States commenced in 1971, but the initial going was slow, as many of the cars (96) had to be referred in a special Ford workshop to address quality issues, and barely 130 were delivered that year. In 1972, the numbers improved, with 1,552 reaching customers.

By 1973, though Ford seemed to have had enough of all the quality shortcomings, and the contract with de Tomaso was terminated, with the clearance of stocks continuing until 1974. Some 5,262 Panteras found buyers in North America. Sales of the Panteras continued in Europe, with numbers picking up once the 330bhp GTS version was introduced in 1973.

With improved quality, the Pantera started looking like a good deal at French Francs 88,000 compared to the other supercars of the period: the Ferrari BB 512 and the Maserati Bora, for instance, retailed for French Franc 190,000 and 142,000 respectively. By the time production came to an end, the sheer length of the product life cycle (from 1971 to 1993) and the total volume sold, of 7,258, made the De Tomaso Pantera the most sold supercar from that era.

Except for the first chrome-whiskered bumper version, which was by Tom Tjaarda, the many later variants, were modified by others. For instance, the first American-spec black moulded bumper iteration was by a young Ford designer Christopher Dowdey, who came up with the well-integrated form in just a week.

The last of the series, the Pantera Si, from 1991, was by the celebrated Marcello Gandini, who reworked the design extensively, yet retained the overall form of the original, as, “I have a lot of respect for Tom’s work, and the Pantera is one of the finest designs from that period,” explained the Italian maestro.

Given greater accessibility and numbers, as well as the possibility to personalize and customize the easier and more reliable mechanicals and body of the Pantera, the model has a cult following as exemplified by the popular Pantera Owner’s Club of America and other similar associations.

Moreover, most of the hardcore fans of the Pantera are also fans of the car’s designer, Tom Tjaarda. “In 1992, I had been invited to the Concorso Italiano event in Monterey, California,” recounted Tjaarda. “Organized by Francis Mandarano, this is one of many events that takes place during the Monterey weekend, the more famous being the Laguna Seca historic races on Saturday and the Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance on Sunday. At that time, Concorso Italiano was just two years old, and it was still somewhat of an experiment.”

“Upon my arrival in Monterey with Paola, my wife, I received a request to have a little chat with the members of the Pantera Club. I had to admit that I did not even know that there was a Pantera Club. They suggested we meet at the Marina High School parking lot on Saturday evening. I thought that it would be a nice little get together with a few car guys, munching on hot dogs and chips and we would talk about the Pantera.

“Paola and I arrived that Saturday evening and found the high school parking lot, but it was empty except for a few Panteras parked there, as well as other cars. There was nobody to meet us, no barbecue, nothing. We kept waiting and were getting upset, when the main doors of the high school opened and out came a man saying, ‘Please come in, we have been waiting for you.’ Inside it was incredible – the Pantera Club had set up elaborate round dinner tables and there were hundreds of people waiting for us!”