by Peter Robinson

Ours was not the most jovial table in the dining room of the Geneva airport’s Movenpick Hotel that Saturday evening in August 1990. We dithered over the fish, sipped the Chardonnay and looked, well, embarrassed. Guilty that our hosts, the people responsible for the car we’d been driving all day, were paying for the meal.

In our subdued mood, we pondered the motives and engineering philosophy of a car company capable of producing such appalling mediocrity.

We had no answers, only a thousand questions: but there were no engineers or product planners or designers, let alone senior executives, in Geneva to quiz about Ford’s all-important fifth-generation Escort.

We found it hard to fathom how the Ford of the Cortina and the front drive Escort (during the mid-1980s the world’s best-selling car) and especially the XR3, Twin Cam and RS1800, and original Mustang and Sierra Cosworth could have produced so desperately an ordinary car. Perhaps knowing that, Ford cynically decided to leave the defence of the mighty FoMoCo to one humble public relations person?

Early that morning, encouraged by the exciting prospect of a day in the latest CE14 (C for its segment size, E for the fact that it was a European car, unlike the later CDW27 Mondeo which was a segment overlapping ’World’ car) of the UK’s best-selling car, we’d driven three different new Escorts out of the hotel car park.

Hours and hundreds of miles later, after comparing the Escorts with the soon-to-be-replaced Volkswagen Golf Mk II and Vauxhall Astra, and the new Fiat Tipo, we could only marvel at the depth of Ford’s arrogance and the unbelievable shallowness of its one-billion-pound new model.

In what was the most damning story in my 60 year-career writing about cars, the Autocar’s (to be accurate, still Autocar & Motor) August 29, 1990 verdict began, “How can Ford have got it so wrong? The flaws in the new Escort/Orion are so obvious we begin to wonder, naively perhaps, if the engineers and product planners have driven the competition in any serious manner. And even if they have, do the right men in the key positions understand what gives a car the flair, poise and balance that makes it more than just mere transport? Or is Ford so influenced by its accountants and marketing department that their vast budget was only spent in the most visible ways?

“These are serious questions to have to ask the world’s second biggest car maker after driving and analysing its new, and potentially top selling model.

“You will know by now that in these three twin tests we came away preferring to drive the Ford’s Italian, German and British rivals, even though two of them are about to be replaced by new models.

“And that is an appalling indictment.”

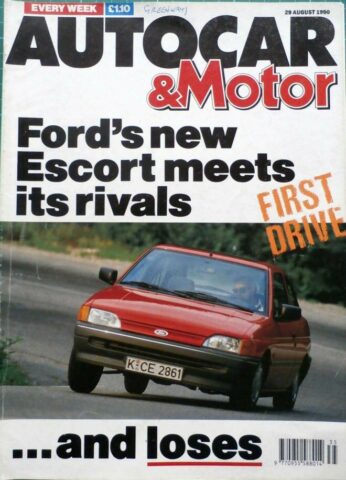

The magazine’s cover, perhaps the most dramatic and provocative in its now 128-year history, showed a red Escort cornering, and carried this provocative cover line “Ford’s new Escort meets its rivals…and loses”.

Autocar was not alone in its criticism.

That August 29 issue came out on the Wednesday morning the Fleet Street motoring correspondents flew to the Escort launch. Most ended up buying the magazine to read on the plane. Unsurprisingly and almost universally (Stuart Bladon wrote on Oracle, “they are outstanding”), they reiterated our verdict, though none were as critical. Car magazine, which never liked to be seen as a follower, buried its Escort first drive on page 126 of the October issue. Still, Car concluded that “there’s little pleasure to be gained from driving the new Escorts and Orions”. The new model was “workmanlike and competent, but what sort of recommendation is that for a car of the 1990s?” The magazine quoted a Ford marketing strategist as saying that “we wanted a middle-of-the-road-car because we sell to middle-of-the-road people”. If so, the company certainly succeeded.

Little wonder Ford Australia rejected the Escort and choose to take the Mazda 323 derived Ford Laser.

A furious Ford immediately struck back. (Now Sir) Ian McAllister, then chairman of Ford GB, summoned Haymarket (publishers of Autocar) executives, advertising director Simon Daukes, editorial director Mel Nichols and Bob Murray, Autocar’s editor, to his office in Brentwood.

His opening line:

“You bastards have killed the Escort”.

McAllister insisted the magazine retest the Escort, admit the magazine was wrong and demanded a favourable review. Haymarket refused. Nichols remembers reminding McAllister that Autocar was an older brand than Ford (1895 versus 1903) and that without editorial integrity the magazine was nothing. There would be no apology or retest. If Ford wanted favourable reports, it only needed to build better cars.

Oglivy and Mather, Ford’s advertising agency, was instructed to remove Haymarket magazines from Ford’s media schedule. If the direction, resisted by the agency, had gone ahead it was initially estimated to cost Haymarket almost half a million A-dollars. In the end only Autocar – and not What Car? – suffered a loss of advertising and cost the company little financial pain.

Through September, Autocar’s readers debated the story in the letters page. Many, never having driven the new car, still supported Ford and claimed, “it’s Ford-bashing season again”. One called the Escort “one of the great anti-climaxes of all time.”

Despite McAllister’s response, inside Ford the realists moved quickly. Within a fortnight of the magazine’s appearance, and after building hundreds of 1.4s, Ford halted production of the 1.4-litre models to ensure that all 1.4 Escorts and Orions were fitted with the front anti-roll bar and springs already mounted to the 1.6 models. This to correct what we called “soggy handling and excessive body roll” though it meant the best-selling version didn’t go on sale until the end of September.

Later, we learned that the car was always designed to have the front anti-roll bar and its deletion – demanded by the bean counters to reduce costs – was against the engineers’ wishes.

“Autocar & Motor’s verdict was undoubtedly the toughest in Europe, a spokesman told the magazine. “Your remarks about the 1.4’s suspension in particular led us to this decision.” Initially, Ford claimed all models would go on sale together, but there were also production and distribution problems that meant the estate and cabriolet finally hit the streets months behind schedule.

The slow launch sales were not helped by Ford’s pricing policy. The old Escorts went up more than 12 percent in 1989, the last rise coming just a couple of weeks before the introduction of the new model. This allowed the salespeople to boast that the new models cost no more than the old. An old trick, not confined to Ford. Despite this the new Escort didn’t seem a bargain, and in January 1991 Ford upgraded the LX variant and introduced a new price leading L model. Sales continued to suffer and the Escort languished in fifth place in the top 10 sales chart in January 1991, though eventually, after a massive marketing effort, it did regain top position.

A new look Escort hit the market in September 1992, the most obvious change an odd ovoid shaped grille, a reflection of, “a new corporate styling theme designed to give Ford a more readily recognisable visual identity.”

The engineers worked hard to improve the NVH of the 1.6-litre engine but seemed to ignore the diesel that still droned between 120km/h and 145km/h and vibrated when accelerating. Ride and handling some showed progress. A better equipped Ghia version, bringing a veneer of opulence, was added to the range.

In volume two of Secret Fords, Steve Saxty’s brilliant book that provides readers with a fascinating behind the scenes look at Ford of Europe top secret unrealised proposals, engineering boss Richard Parry-Jones admits to being appalled upon driving a rental Escort with no power steering.

“It was unambitious and out of step with quality aspirations: hard grey plastic, cheap materials and no perceived quality – cost reduced versus plainly engineered. The styling was anonymous and, while it wasn’t unsafe to drive, it was dreadful – harsh, noisy and uncomfortable. No pleasure.”

Years later Parry-Jones told Nichols the Autocar story was the trigger for the bean-counters being over-ruled and his being promoted and liberated to spend more and make good cars.

In 1990 RPJ was running Ford’s Cologne plant and expecting to move to the VW/Ford plant in Portugal. In April 1991, following the Escort’s launch, Parry-Jones was told he was needed to run Ford’s German Merkenich R&D centre as Chief Vehicle Engineer to further develop the new Mondeo and sort out the Escort facelift, which meant improving the steering and handling, reduced noise vibration and harshness. “It wasn’t perfect but was the best we could do with what we had.”

As for the bland styling: after the bold and controversial Sierra, a risk-averse Ford wanted a conservative and cheap to build model. Program design manager Helmuth Schrader said, “The (design) objective was to produce market research winners – which we did. Management wanted to look at quantifiable data rather than live with uncertainty and any inherent risk that it was no longer willing to take.”

By the time the empowered R P-J signed off the Mondeo before its launch in 1993, Ford’s profound philosophy shift had transformed the way the company developed cars. For which a generation of motorists – and not just enthusiasts – should be grateful.